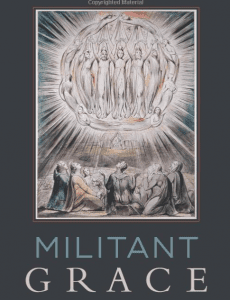

What does it mean to call Dietrich Bonhoeffer an apocalyptic ethicist or theologian? Philip Ziegler, in his new important study on apocalytpic theology, Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology, contends against the grain that Bonhoeffer (=DB) was an apocalyptic ethicist.

What does it mean to call Dietrich Bonhoeffer an apocalyptic ethicist or theologian? Philip Ziegler, in his new important study on apocalytpic theology, Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology, contends against the grain that Bonhoeffer (=DB) was an apocalyptic ethicist.

Is Bonhoeffer’s moral theology apocalyptic? This question is unsettled from L front to back. The texts that constitute Bonhoeffer’s Ethics are unsteady though well-worked fragments of the actual theological ethics he hoped to write. More unsettled still is the meaning of “apocalyptic,” whose popular and scholarly valences are as many as they are divergent and contested. Even if one could steady the question, prospects for a positive answer appear remote. Readers of the Ethics have not been led to the idea of “apocalyptic”: quite the opposite. One possible exception here is Larry Rasmussen, who does associate Bonhoeffer with apocalyptic eschatology. Yet even he considers the association forced: turning to apocalyptic means diverging from Bonhoeffer, who was “almost immunized” against such an eschatological perspective by Lutheran confessional and German academic traditions, says Rasmussen.” [SMcK: Criticism of Rasmussen was clear on this very point.]

Undeterred in going against the grain of DB scholarship, which is formidable, Ziegler says,

I want to argue that in draft upon draft of his Ethics manuscript, Bonhoeffer is definitely working out a theological ethic whose intent is to conform to the contours of Paul’s apocalyptic gospel.

He is undeterred because of the rise of apocalyptic Pauline theology that fits more with Barthianism (and some would say is Barthianism) and therefore with DB.

Recent reconsideration of Pauline apocalyptic by de Boer, Martyn, before them also J. Christiaan Beker, and others has discerned with renewed clarity, as we have seen, that in Paul’s gospel “revelation” (apocalypsis) denotes God’s redemptive invasion of the fallen order of things such that reality itself is decisively remade in the event. God’s advent in Christ utterly disrupts and displaces previous patterns of thought and action and gives rise to new ones that better comport with the reality of a world actively reconciled to God.

There is some slippery land to navigate here. For many, apocalyptic for Paul must fit into Jewish apocalyptic which is both a genre and a kind of theology, while for this new group it’s only marginally about Jewish apocalyptic, not about a genre, and more about how best to describe the revelation of God in Christ and its radical impacts on everything it touches (which is everything).

Apocalyptic, on this view, is more than a literary genre or a form of extreme ancient rhetoric; it is a mode of theological discourse fit to give voice to the radical ontological and epistemological consequences of the gospel, consequences intensely relevant to doing Christian ethics. The basic moral question that Paul’s apocalyptic gospel demands to be asked and answered is this: “What has paraenesis to do with apocalypsis?”

Which leads to his first question to establish his case: What is apocalyptic gospel? Here he opens the door to the common terms like radical, ontological, newness, incursions and disruptions.

Rather, it denotes an understanding of Christ as “the effective and definitive disclosure of God’s rectifying action” whereby the old “world or age is destroyed and brought to an end.” [It] is shorthand for a distinctive acknowledgment of the divine identity and eschatological importance of Jesus Christ. … Paul’s witness is that what takes place in Christ is the incursion of God’s power into the world with effect. Revelation is “no mere disclosure of previously hidden secrets, nor is it simply information about future events.” For revelation itself is an event that initiates, even as it discloses, a new state of affairs; not simply “a making known,” revelation is also “a making way for,” involving God’s conclusive “activity and movement, an invasion of the world below from heaven above.” The event in which God is made known as Savior, the coming of the Christ, is the very event that saves. We might say concisely: divine revelation is redemption. The gospel is not mere reportage but brings to bear “the power of God for salvation” (Rom. 1:16; 1 Cor. 1:18). Yet it is testimony: a telling of the “good news” that human captivity to sin is ended by God’s graciously powerful rescue.

A key then is his claim: revelation is redemption. The redemption in Christ is the revelation of God. There’s more, something altogether new is now reality:

If the identification of revelation and redemption in this way is a first hallmark of Paul’s apocalyptic discourse, a second is its claim that evangelical talk is talk of reality. The gospel speaks of what has taken place and of the state of affairs that God’s “incursion” or “invasion” for sinners’ sake has actually brought about.

Now we are alerted to the fact that those who hear its message are always already implicated in that of which it speaks. The logic of the apocalyptic gospel is thus never one of possibility. It does not take the form “if . . . then,” and it is not an offer to be realized only on its acceptance.

o, for example, Martyn restates the primary message of Galatians simply as ‘”God has done it!” . . [And] there are two echoes: ‘You are to live it out!’ and ‘You are to live it out because God has done it and because God will do it!’ Such a gospel, as de Boer says, “has little or nothing to do with a decision human beings must make, but everything to do with a decision God has already made on their behalf,” which is identified with God’s enactment of salvation in Christ. Reconciliation is real, and so God’s gracious justification establishes our “true position in the world” without awaiting our permission.

Two observations here: (1) this means apart from human will one is saved, and thus there is an implicit universalism (not as potential but as reality), and (2) this theology cannot escape supersessionism or even colonizing of all other faiths. God has done it means God has saved the Torah observant who is non-messianic in faith through God’s revelation in Christ. If it is altogether new, then the old (Judaism) is now taken to a new level or, more consistently, undone and reconfigured in Christ.

These points aside, What about DB?

Ziegler contends two themes of apocalyptic are characteristic of DB’s ethics and theology, and Ziegler is right on DB’s characteristic themes (though I’m not sure I’d call his ethics apocalyptic so much as Christocentric, and there’s a difference in framing in these two terms):

What Bonhoeffer said of Discipleship is no less true of the Ethics that followed it. Here too justification shows itself to be central to the proceedings. Bonhoeffer distinctly expounds the doctrine through the interplay of three central categories: revelation, reconciliation, and reality. And these categories are freighted with the logic of Pauline apocalyptic. This can be discerned most sharply in the two claims that structure all of Bonhoeffer’s theological ethics: first, that revelation is reconciliation, and second, that the event of reconciliation in Jesus Christ is constitutive of reality.

The realism that Bonhoeffer sets over against all idealism in church and theology is thus apocalyptic. Since “revelation gives itself without precondition and is alone able to place one into reality,” he says, serious theological ethics, no less than dogmatics, must struggle for forms of thinking appropriate to God’s apocalypse in Christ Jesus. The ages having turned, Christians are alert to the fact that they stand together with all others in a world whose reality has been both taken apart and put back together with effect by God’s redemptive triumph through the cross: it has become Christ-reality.