One of the world’s truly great historians today is an Oxford scholar of the English Reformation, and his name is Diarmaid MacCulloch (Dur-mudd).

One of the world’s truly great historians today is an Oxford scholar of the English Reformation, and his name is Diarmaid MacCulloch (Dur-mudd).

Years back I read his massive book Thomas Cranmer, and just a year or two ago I read his All Things Made New, a collection of shorter writings on the Reformation.

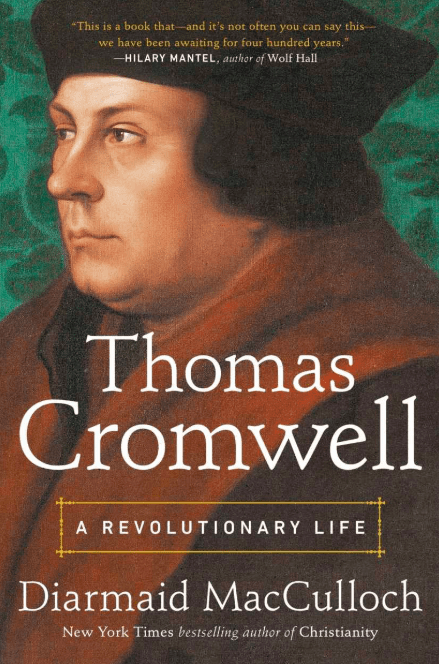

Now he continues his work on the English Reformation with a bold and big beast of a book called Thomas Cromwell.

It is not wise today for any church historian to ignore MacCulloch as his profound knowledge of facts and persons and events and connections between all the above and behind-the-scenes secrets is unmatched, as his commitment to a thick description of all things Reformation.

He examines original sources — a student he was of G.R. Elton — and he pours them into a large theory that includes connecting the various Reformations — Germany, France, Switzerland, the USA — to economic, political, ecclesiastical, and personal histories and movements. Names and letters and in-trays and out-trays and why the gaps are the concerns of this book, not what others are saying about Cromwell and England.

This is a book about the world of Cromwell as much about Cromwell. Cromwell set in context, yes, that’s the book’s focus.

I can’t review or even begin to review his Cromwell so want to offer a few big ideas that come from reading MacCulloch.

When I was taught Reformation I was taught Luther and then Calvin and at times and sometimes not at all the Radical Reformers, the Anabaptists of Switzerland and Germany and then the Low Countries. The distinguishing feature of the Reformation was justification by faith, it was about a religious revival of New Testament Christianity, it was about deeply spiritual men and it was about faith, faith, and faith. It was not about politics, it was not about economics, and it was not about personal agendas. The Catholic Church was selling indulgences and the Luther learned salvation was by faith.

I also learned the Reformation — and MacCulloch lands on the same side on this one though for different reasons — was one big movement, one big discovery of grace and faith and justification by faith. It got going in Germany with Luther and then spread to France and Switzerland and then England and naturally then came to the colonies. It was a spiritual virus let loose.

MacCulloch’s study throws sand in the eyes of anyone who’d like to think the various Reformations were primarily a bottom-up and people’s movement or that it was a spiritual virus on the run. He shows time and time again that the Reformations were about powerful men, about the Catholic Church’s reach and the desire to break that reach, about politics and taxation and about powerful people wanting to liberate a country from the Catholic Church.

Cranmer was the theologian of the Reformation in England. Cromwell as a major political activist, and behind it all was Henry 8, and what got the whole thing started?

Henry 8 wanted to divorce his wife, Katherine of Aragon, and marry Anne Boleyn. Divorce was a moral problem in the Catholic Church and England’s king and people were under the Pope. Henry 8 tried for an annulment, got Cranmer to offer (bogus) theological support, and got Cromwell to work on his behalf. It took a long time but eventually the line was severed and Henry 8 married Anne and the Reformation was set in motion.

Cranmer, it is well known, got the worship and homilies and education patterns going — and this all became The Book of Common Prayer and the Homilies.

One of Cromwell’s major tasks — not always with complete support of Henry 8 and always with opposition from the former Catholic Church leaders of England, whom MacCulloch calls the “conservatives” (conserve the Catholic ways of England) — anyway, one of Cromwell’s major tasks was the closing down and appropriation (land, money, properties) of monasteries and institutions with the implication of replacing Catholicism with Protestantism. Cromwell is sketched here as a genuine Protestant who has to be judged by the kind of Protestantism a politician embraced.

MacCulloch doesn’t desecrate the man’s faith; Cromwell comes off as a genuine evangelical/Protestant albeit one not afraid to avoid grace when it came to needing to get someone out of the way.

Henry 8 didn’t just divorce Katherine and then Anne (they were called annulments) but then married Jane Seymour who died, annulled the marriage with Anne of Cleves, executed the next one in line, Catherine Howard and then finally married Catherine Parr. Cranmer’s job was to defend him theologically.

Henry executed more than his wife; he executed theological opponents — both Catholics and Protestants who created a stir. Cromwell was one of them though Henry 8 later admitted Cromwell was his best servant ever. Cromwell, the king’s admin man, had blood on his hands often; the portrait here is realistic, a kind of 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings or 1-2 Chronicles narration. There is no hagiography.

Cromwell wanted a deeper Reformation so he found a wife for Henry 8 from the Protestant ledger, namely, Anne of Cleves — whom the king thought ugly when he met her just before the wedding! This put Cromwell in trouble, Cromwell doubled down on Reformation agendas, a flank was exposed and Henry 8 beheaded the man.

That’s not the end of the story, of course, and the turbulence between a Catholic England and a Protestant England didn’t end there… but Cromwell was an administrative genius and got England set for what became the fuller version of the English Reformation.

I wanted more religion, more revival, more about the people’s desire to embrace the gospel of grace in the Protestant Reformation, but the side of the Reformation told by MacCulloch is one that has to be told. Lots of what we’d like to idealize just wasn’t so. There was lots of blood, lots of gore, lots of unholy alliance between politics and power with the message of the Reformation. Liberation from Rome then was not just a religious motive but potently an economic and political liberation movement.

A word about MacCulloch’s prose. It’s his style and there are not many like him, which is good; you can’t skim the man; his sentences can be long and he can put twelve ideas or facts in one paragraph. At times I paused and muttered, “I wonder how many hours that sentence required.”

There’s so much more to say … Cromwell supported translating the Bible into English and getting a Bible into every church, he got major influencers (like Hugh Latimer) into positions … and one thing I’d want to say is that it is unfair to the man to think he was nothing but a political tool.