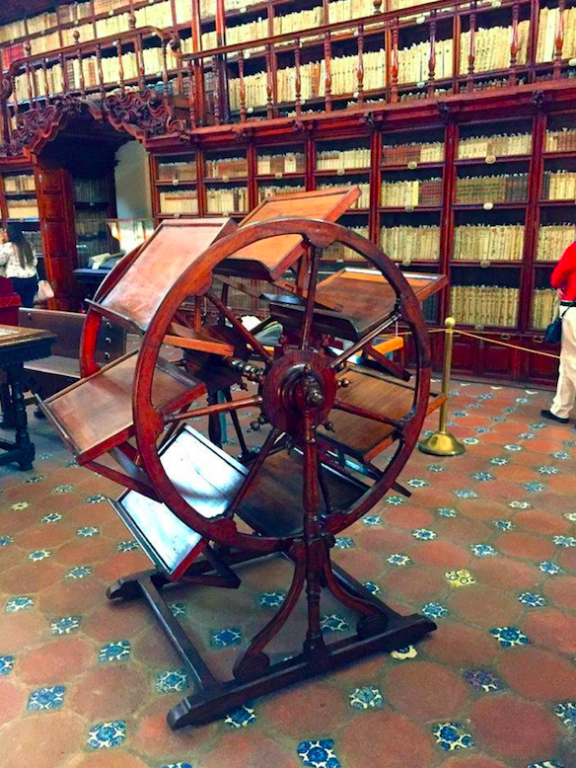

Seven books to consult at once!

A new blog and an exceptional post by David Cramer:

In case you missed it, last month there was a bit of a blogosphere dust-up when religion writer Jonathan Merritt tweeted that it was “weird” that evangelical historian Thomas Kidd used the word “evangelical” to describe Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American poet.

A number of evangelical historians came to Kidd’s defense (as is well documented by historian John Fea), and the conversation quickly shifted to the questions of how to define “evangelicalism” and who should do it.

I followed this conversation with some amusement because I was at the same time reading Merritt’s latest book, Learning to Speak God from Scratch, where he argues that Christians should be liberated to play with religious words to breathe new life into them, and he notes that the advent of dictionaries and their seemingly rigid and prescriptive definitions have hindered our ability to do so.

In light of the argument of his book, Merritt’s insistence that Kidd use the word “evangelical” in conformity with his seemingly prescriptive definition seemed a bit—for lack of a better word—weird.

If Merritt had applied the approach of his book to the word “evangelical,” I think he would have seen how the word, like many religious words, has morphed and evolved over time and is used in different ways based on its context. There’s no Platonic essence of evangelicalism, but rather, as Wittgenstein argues in Philosophical Investigations, the meaning of a word is found in its use.

While Merritt is correct that it would be weird to consider Wheatley an evangelical in certain times and contexts, Kidd’s use of the term is quite appropriate relative to the time and context he was describing.

In Merritt’s defense, it has become nearly, might we say, useless to use the word “evangelical” without some accompanying adjective to specify whom or what one is describing—as Kidd himself has elsewhere acknowledged.

In my last post, I mentioned an article by one of my former college professors and personal mentors, Timothy Erdel(“Brother Tim”), in which he defines “evangelical” from a number of angles: historical, contemporary, theological, and behavioral.* In this post, I want to focus on the seven historical meanings of “evangelical” he describes in order to answer whether and how they’re compatible with Anabaptism.

What does a theologian do? Brian Harris:

It’s a question I’ve been asked often enough, especially after I’ve introduced myself as a pastor and theologian, “So what do theologians do?”

Let’s note the obvious. By definition, theology, being made up from two Greek words theos (God) and logos (the word about, or the study of), is the study of God. By implication then, all those who grapple with the question of God are, in one way or another, theologians. They might be very poor theologians, amateur theologians, professional theologians, perhaps even theologians whose work is widely recognized in the life of the church – but theologians they are. Given the nature of this blog, I would imagine that the vast majority of those who visit its pages are, in the broad sense of the word, theologians.

So what do theologians do and what makes for a good theologian?

First up a warning. Theology is a dangerous business. Though we might begin by feeling that we are in control of the process (we study God) we soon discover that the God we study is the God who studies us. Even as we examine the nature and character of God, we sense the pushback, “You think you are studying me – but actually I am studying your response to what you discover. Never forget, those who study God are challenged to live in the light of what they find.” It is dangerous to be a theologian and to be resistant to change, for you cannot study God and not change. Rudolf Otto in his classic The Idea of the Holy speaks of our encounter with the mysterium tremendum et fascinans – and it is probably as well to leave that untranslated from the Latin as it better conveys a sense of the weight of what we experience (though for those who insist on a translation, try the “fearful and fascinating mystery”). To put it crassly, you cannot spend the day contemplating the mysterium tremendum et fascinans and then calmly ask, “So what’s for dinner?”

What makes for a good theologian? Ideally they will play a number of roles, but let me focus on three P words that cumulatively suggest something of the calling of the theologian…

What’s an evangelical to do? What’s an evangelical? James Bratt:

Historians have been adding their own bit to the flood of commentary about the relationship of evangelicals to Donald Trump, and the guild has been just about as hostile on the subject as the rest of the intelligentsia. That has put an extra burden upon those Christian historians who, loyal to the faith while appalled at the man, want to salvage the first from association with the second. Some, like my dear friend and mentor George Marsden, argue that evangelicalism is not, after all, mostly about politics but about religion. For his part, Baylor University historian and former Marsden student Tommy Kidd believes that a great many among the 80+ percent of self-professed evangelicals who support Trump are not genuine evangelicals at all, being lax in church attendance, knowledge of scripture, rudimentary theological literacy, etc., etc.

Judging from last weekend’s conference, most historians—including Christian historians—are not buying it. In the wake of 2016 they have turned new eyes upon the past and are finding that what the Trump election exposed in “evangelical” ranks has been there all along: racism, misogyny, militant American nationalism, deference to corporate capitalism, a cult of arms and violence, all high on a mixed cocktail of persecution complex and triumphalism. Previous exculpatory evidence (Billy Graham defied Jim Crow at his Southern rallies) now bows beneath a heavier load (Billy Graham wouldn’t recognize structural racism if it bit him on his blessed bottom, and it was the sainted Dwight L. Moody who conceded to segregated revival meetings in the first place)….

If the international focus [USA evangelicalism is narrower than international evangelicalism] offers some redeeming possibilities, I think the Marsden and Kidd options won’t fly—at least for a while. The current American scene, along with even a chastened Kuyperianism, argues against any clean segmentation of religion from politics. Nor is “evangelicalism’s” status as a political category a recently born corruption.

[Now the money quote:] If you rise with 1976, you can’t help but fall with 2016. “Evangelicalism,” especially in its white American version, has been political in its character as well as its appeal from the start.