A good week — some translating and I spoke at Spring Arbor U in Michigan. Plus, as noted below, Katie Bouman’s imaging of the black hole is now public.

A good week — some translating and I spoke at Spring Arbor U in Michigan. Plus, as noted below, Katie Bouman’s imaging of the black hole is now public.

It is a sad reality that many women’s stories end up in a black hole in various church groups. We have #MeToo, #ChurchToo, and now #MissionsToo. Dalaina May deserves our attention, folks.

The #MeToo movement has successfully pulled back the curtain on hidden misogyny and rampant abuse of women in US culture. #ChurchToo has highlighted the sexism that’s just as alive in American pews and pulpits. Women from churches around the country have shared their stories of being abused, silenced, and sidelined. As I read these accounts, I sympathized deeply. I have my own #MeToo stories and #ChurchToo stories. Yet, I also have #MissionsToo stories and they have yet to be given space in these movements.

The child of conservative missionaries, one of my first memories when we moved overseas was listening to the teary words of my mother’s friend, a woman recently arrived from the United States. “He’s my husband, and he believes that we should be overseas. My role is to be his helpmate and to submit to his leadership, so I am here to help him fulfill the calling that God gave him even though I never wanted to come.”

I was only eleven years old and trained by my community to believe that these words were gospel truth. Still, silent panic welled in me as I realized the implications of her words: a woman could be forced into moving overseas simply because her husband said so.

As I got older, I realized that this, while tragic and unjust, was mild in comparison to many other stories currently emerging from the mission field. Accounts of domestic violence, covered up child sexual abuse, and the alienation of women in missions leadership are not unusual. At its worst, the mission field has been a prison for women and children, conveniently far away from the eyes of caring family and friends, and away from the protective laws and resources available to victims of abuse in their home countries.

When I began my own missionary career as a young mother, I connected online with an American woman in her early twenties who grew up in Asia. Her family ascribed to the “daughters at home” movement, a hyper-patriarchal subculture in which women are under the authority of their fathers until they marry and come under the authority of their husbands. Women in this movement are seen primarily as daughters/wives/mothers, and their role is to care for the home and support the men in their lives.

For this young woman, it meant that she wasn’t allowed to return to the United States or enroll in college. She was required to stay in her parents’ home and serve them as they continued their ministry until she married the man of her father’s choosing.

Over the course of our relationship, she attempted multiple times to get a job locally and move out of her parents’ home. Each time, she was threatened with expulsion from the family, shamed for her “sinful rebellion,” and spiritually abused by her parents and older brothers. Eventually, she canceled her plans to move out and tried to appease her family by returning to dutiful submission. She is one of the faces of #MissionsToo—a woman isolated from resources and suffering under the hammer of misogyny.

For other women, #MissionsToo looks like a wall of unacknowledged contributions, silenced voices, and stifled ministries. And it’s nothing new.

Thank you Kyle Korver:

What I’m realizing is, no matter how passionately I commit to being an ally, and no matter how unwavering my support is for NBA and WNBA players of color….. I’m still in this conversation from the privileged perspective of opting in to it. Which of course means that on the flip side, I could just as easily opt out of it. Every day, I’m given that choice — I’m granted that privilege — based on the color of my skin.

In other words, I can say every right thing in the world: I can voice my solidarity with Russ after what happened in Utah. I can evolve my position on what happened to Thabo in New York. I can be that weird dude in Get Out bragging about how he’d have voted for Obama a third term. I can condemn every racist heckler I’ve ever known.

But I can also fade into the crowd, and my face can blend in with the faces of those hecklers, any time I want.

I realize that now. And maybe in years past, just realizing something would’ve felt like progress. But it’s NOT years past — it’s today. And I know I have to do better. So I’m trying to push myself further.

I’m trying to ask myself what I should actually do.

How can I — as a white man, part of this systemic problem — become part of the solution when it comes to racism in my workplace? In my community? In this country?

These are the questions that I’ve been asking myself lately.

And I don’t think I have all the answers yet — but here are the ones that are starting to ring the most true:

I have to continue to educate myself on the history of racism in America.

I have to listen. I’ll say it again, because it’s that important. I have to listen.

I have to support leaders who see racial justice as fundamental — as something that’s at the heart of nearly every major issue in our country today. And I have to support policies that do the same.

I have to do my best to recognize when to get out of the way — in order to amplify the voices of marginalized groups that so often get lost.

But maybe more than anything?

I know that, as a white man, I have to hold my fellow white men accountable.

We all have to hold each other accountable.

And we all have to be accountable — period. Not just for our own actions, but also for the ways that our inaction can create a “safe” space for toxic behavior.

Tax season is upon us–and by us, I mean everyone who is not Amazon, Netflix, Chevron, or pharmaceutical manufacturer Eli Lilly and Co., because they are among the 60 or so corporations that paid zero dollars in federal income taxes on the billions of dollars in profits they earned in 2018.

That’s according to a new analysis, released today by the Washington-based think tank Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) and first reported by The Center for Public Integrity. After analyzing the 2018 financial filings of the country’s largest 560 publicly held companies, they found that companies like Amazon and Netflix were “able to zero out their federal income taxes on $79 billion in U.S. pretax income,” thanks to the tax overhaul bill pushed through Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump.

“Instead of paying $16.4 billion in taxes, as the new 21% corporate tax rate requires, these companies enjoyed a net corporate tax rebate of $4.3 billion, blowing a $20.7 billion hole in the federal budget last year,” ITEP reported.

As former Senator Bob Dole (R-KS) once said, “The purpose of a tax cut is to leave more money where it belongs: in the hands of the working men and working women who earned it in the first place.” While the corporate tax laws probably needed some overhauling (Obama fought to make them more globally competitive), when hardworking Americans have to pay taxes, in some cases more than in previous years, and billion-dollar, profit-making corporations have to pay nothing, it’s hard to see who this new tax bill is benefitting.

Of course, as Albert Einstein said, “The hardest thing in the world to understand is the income tax.”

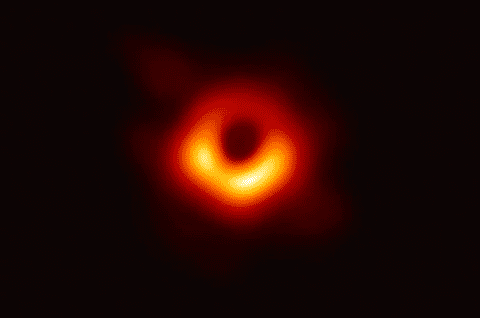

Good for Katie Bouman:

The development of the algorithm that made it possible to create the first image ever of a black hole was led by computer scientist Katie Bouman while she was still a graduate student at MIT. Bouman shared a photo on Facebook of herself reacting as the historical picture was processing.

The algorithm, which Bouman named CHIRP (Continuous High-resolution Image Reconstruction using Patch priors) was needed to combine data from the eight radio telescopes around the world working under Event Horizon Telescope, the international collaboration that captured the black hole image, and turn it into a cohesive image.

Bouman is currently a postdoctoral fellow with Event Horizon Telescope and will start as an assistant professor in Caltech’s computing and mathematical sciences department, according to her website.

The development of CHIRP was announced in 2016 by MITand involved a team of researchers from three places: MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and the MIT Haystack Observatory. As the MIT described it three years ago, the project sought “to turn the entire planet into a large radio telescope dish.”

Since astronomical signals reach the radio telescopes at slightly different rates, the researchers had to figure out how to account for that so calculations would be accurate and visual information could be extracted.

Today’s students see themselves as digital natives, the first generation to grow up surrounded by technology like smartphones, tablets and e-readers.

Teachers, parents and policymakers certainly acknowledge the growing influence of technology and have responded in kind. We’ve seen more investment in classroom technologies, with students now equipped with school-issued iPads and access to e-textbooks. In 2009, California passed a law requiring that all college textbooks be available in electronic form by 2020; in 2011, Florida lawmakers passed legislation requiring public schools to convert their textbooks to digital versions.

Given this trend, teachers, students, parents and policymakers might assume that students’ familiarity and preference for technology translates into better learning outcomes. But we’ve found that’s not necessarily true.

As researchers in learning and text comprehension, our recent work has focused on the differences between reading print and digital media. While new forms of classroom technology like digital textbooks are more accessible and portable, it would be wrong to assume that students will automatically be better served by digital reading simply because they prefer it.

Speed – at a cost

Our work has revealed a significant discrepancy. Students said they preferred and performed better when reading on screens. But their actual performance tended to suffer.

For example, from our review of research done since 1992, we found that students were able to better comprehend information in print for texts that were more than a page in length. This appears to be related to the disruptive effect that scrolling has on comprehension. We were also surprised to learn that few researchers tested different levels of comprehension or documented reading time in their studies of printed and digital texts.