Sometimes St. Augustine makes my head ache.

Sometimes St. Augustine makes my head ache.

He is fascinating, faithful, and far from perfect. His literal interpretation of Genesis is not really what we would term literal in the modern sense. Craig Allert, in Chapter 7 of Early Christian Readings of Genesis One: Patristic Exegesis and Literal Interpretation digs into Augustine and his writings on the days of Genesis 1. To begin to understand Augustine it is necessary to look at his view of time and its relationship to God. Augustine placed God outside of time, with time part of creation. In his view, to do anything else meant that God was subject to change and this violated his philosophical views of God. Allert quotes from Augustine’s Confessions, but the same general idea is found in other writings as well.

Some philosophers considered creation as implying an act of will at some point in time by God, and an act of will implies change in God: “If some change took place in God, and some new volition emerged to inaugurate created being, a thing he had never done before, then an act of will was arising in him which had not previously been present, and in that case how would he truly be eternal?” (p. 269)

Augustine read Scripture within the confines of his extra-biblically determined view of God. (John Calvin did the same and it may well be that none of us completely escape this trap.) Later Allert quotes Augustine from The City of God.

Time does not exist without some movement and change, but there is no movement or change in eternity. Time simply would not exist if no creature had been made to bring about change by means of some motion.

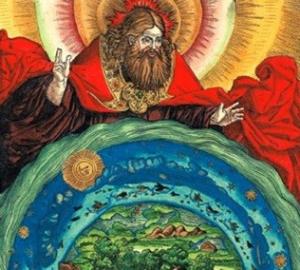

Therefore, since God, in whose eternity there is no change whatsoever, is the creator and governor of time, I do not see how it can be said that he created the world after expanses of time, unless it is claimed that, prior to the world, there was already some created being by virtue of whose motions time was able to pass.

For Augustine, the “holy and utterly truthful Scriptures” tell us that God made heaven and earth in the beginning so that we might know that nothing was made prior to this. If this were not so, he says, Scripture would have told us. Thus, it is “beyond doubt” that the world was not created in time but rather with time. No time could have passed when there was no created being, because created beings provide the change and motion of which time is a function. (p. 273)

Augustine’s understanding of time is not all that different from our modern scientific understanding. Time began with the big bang. Augustine’s understanding of time and creation lead him to some rather interesting conclusions. For example, angels and spiritual beings are creatures active in time and part of creation (not eternal like God himself). How does this fit into the Genesis account? Consider the opening verses:

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light “day,” and the darkness he called “night.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.

For Augustine this “light” wasn’t the electromagnetic radiation (photons) we understand as “light.” From book 4 of the Literal Meaning of Genesis as quoted by Allert:

We should say the light created originally is the forming and shaping of the spiritual creation, while the night is the material of things still to be formed and shaped in the remaining works, material that had been laid down when in the beginning God made heaven and earth, before he made the day by a word.

Thus, the light that was originally created is a “spiritual, not a bodily light.” How is this spiritual light related to the evenings and mornings that are indicated in the Genesis account? Augustine has already told us that the creation of light in Genesis 1:3 refers to the illumination of the angels. He reasons that the claim in Genesis 1:1 that God made the heavens must include the angels, but since no lapse of time is involved, they must be in an unformed state until God illumines them. The spiritual light (the angels), Augustine explains, was created after the darkness that was over the abyss. He understands this as meaning its transition from its unformed state toward its formation by the Creator. In a similar manner, morning was made after evening, which means that once it knows its own nature (that it is not God), it returns to praise God, who is the true light who formed it in the first place. (p. 282)

The other days of Genesis repeat this process. Allert summarizes:

[T]he temporal importance of the days fades in the distance. The knowledge of the angels being connected to evening and morning simply repeats itself in the days of creation. Morning indicates knowledge of their own spiritual “higher” order, albeit not what God is, while evening indicates a “lesser degree of knowledge” – that is, a knowledge of the lower order of creation. For Augustine, knowledge of a thing in the Word of God is “day,” while knowledge of its own specific nature is “evening.” (p. 283)

Augustine did not consider this an allegorical or figurative reading of Genesis 1. Rather, as Allert emphasizes (p. 286) he considered it a literal interpretation of the actual creation of the world.

Augustine also considered creation as simultaneous rather over an extended period of time.

Augustine also considered creation as simultaneous rather over an extended period of time.

We are told in Genesis how God finished his work in six days, but Scripture elsewhere tells us that he “created all things simultaneously together.” For Augustine, we should not see this as a contradiction because this one day repeated six or seven times was made simultaneously. The reason why Genesis so “distinctly and methodically” recounts the days is “for the sake of those who cannot arrive at an understanding of the text, ‘he created all things together simultaneously,’ unless scripture accompanies them more slowly, step by step, to the goal to which it is leading them.” (p. 288)

Augustine concluded that God simultaneously planted the “seeds” or ideas and capacities from which the world we know developed.

Allert digs into several other ideas developed in Augustine, including the “beginning” and the role of Jesus in creation. The Word was with God in the beginning and through whom everything was made.

That is why Augustine sees the second person of the Trinity, the Son, in Genesis 1:1. “In the beginning God made … suggests the Word as the source of creation in its initial creation, its ‘formless imperfection.”‘ But when the text states “God said, let it be made,” it is the Son who is being alluded to. His presence at the beginning means that he is the source of creation as it comes into being. But his being the Word indicates his conferring perfection on creation. The Word calls creation back to himself in order to complete it, “so that it may be given form by adhering to the creator.” (p. 300)

This really only scratches the surface of Augustine on Genesis and creation. Allert goes a somewhat deeper, but still only summarizes a rather complex Christian thinker and writer. However we look at it, Augustine did not interpret Genesis 1 in a modern literal fashion. His reading was shaped by his understanding of God and by cultural ideas of his time and place.

We cannot simply refer back to the early church Fathers to find support for modern “literal” approaches to Scripture. Augustine is no exception here. However, we can learn and grow from reading him on Genesis and pondering his writings and views.

What is a literal interpretation of Scripture?

When is a figurative reading appropriate?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.