When I learned recently of John MacArthur’s criticism of the SBC, I immediately thought of Charles H. Spurgeon and the “Downgrade Controversy.” MacArthur, as was recently highlighted in a post on this blog, accused the SBC of losing its faith in biblical authority. The denomination, by MacArthur’s account, had taken a “headlong plunge” toward women preachers: “When you literally overturn the teaching of Scripture to empower people who want power, you have given up biblical authority.”

MacArthur himself is not above criticism. But hands off Spurgeon. If Amy Carmichael is the Protestant Virgin Mary (as I suggested in a recent post), Spurgeon is the 7-point Calvinist’s Apostle Paul. They all praise him sky high. John Piper simply gushes. Mark Driscoll says he was “arguably the greatest Bible preacher outside of Scripture.” Al Mohler delivered the second annual Spurgeon lecture, “God’s Lion in London” in 2014, at Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando. The previous year MacArthur presented the first address at the Midwestern Seminary inaugural Spurgeon Lectureship where he maintained that during the Downgrade Controversy, “Spurgeon’s defense of the truth and concern for integrity follow the pattern set by Paul in dealing with his opponents in Corinth.” And for all the rest of us, we can always go out and purchase a leather-bound KJV Spurgeon Study Bible—only $53.65, Amazon Prime.

Spurgeon, like MacArthur, cited fellow Baptists for giving up biblical authority, particularly on issues related to his staunch Calvinism. “Arminian perversions,” he railed, will “sink back to their birthplace in the pit.” The belief that a person could lose salvation was “the wickedest falsehood on earth.” MacArthur’s focus has been most recently on women’s ministry. His two words for Beth Moore were: “Go home”—where she belongs.

It was harsh, but MacArthur, as he writes of Spurgeon, “could no longer refrain from criticizing the church’s alarming departure from sound doctrine and practice.” Spurgeon, like Paul, faced opposition from those who “hated the gospel,” those in the Baptist Union—the same kind of dangerous opponents MacArthur encounters among Southern Baptists. Spurgeon had a “godly conscience,” and was waging “a battle for doctrinal purity”—just like MacArthur himself. It was a battle for the Bible, a battle for Truth.

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892) was London’s most celebrated megachurch minister of his day. The son and grandson of independent nonconformist ministers, he had a mediocre childhood education. The first-rate studies available to Anglicans were not accessible to him, nor did he have the desire or mentality for such an education. He often told of the simple sermon from Isaiah 45 (“Look unto me and be ye saved”) that led to his conversion as a teenager: “Well, a man needn’t go to college to learn to look. . . You may be a fool and yet you can look. . . but if you obey now, this moment you may be saved.” He began preaching shortly after this, and his reputation as a mesmerizing speaker spread quickly. At eighteen he was a pastoral candidate at the prestigious New Park Street Chapel. After listing to boring sermons from other candidates, the congregation chose him.

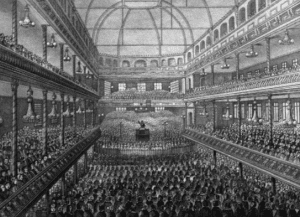

In 1861, still in his twenties, his congregation moved to the new Metropolitan Tabernacle. Here his preaching ministry continued to thrive. He paced the platform and turned biblical figures into real life heroes or villains. He was the best show in town, and crowds lined up early to get good seats.

Fifteen years ago, John and I made a quick visit on a weekday afternoon to the Metropolitan Tabernacle while we were in London. I particularly recall coming up to the grand stairway entrance and finding it blocked by a temporary metal pipe fence. Very few people were around and we found our way to a locked back door where we rang a bell and were buzzed in. We spent a short time browsing the shelves of a good-sized bookstore, finding nothing besides writings either by or about Spurgeon. The main auditorium had burned twice since Spurgeon’s day and had been significantly downsized. We left with the feeling that we’d visited an empty museum—a dry-bones skeleton of megachurch entertainment of a bygone era. After an era of a small dwindling congregation, numbers seem to have grown in recent years, though still a barebones ministry.

Fifteen years ago, John and I made a quick visit on a weekday afternoon to the Metropolitan Tabernacle while we were in London. I particularly recall coming up to the grand stairway entrance and finding it blocked by a temporary metal pipe fence. Very few people were around and we found our way to a locked back door where we rang a bell and were buzzed in. We spent a short time browsing the shelves of a good-sized bookstore, finding nothing besides writings either by or about Spurgeon. The main auditorium had burned twice since Spurgeon’s day and had been significantly downsized. We left with the feeling that we’d visited an empty museum—a dry-bones skeleton of megachurch entertainment of a bygone era. After an era of a small dwindling congregation, numbers seem to have grown in recent years, though still a barebones ministry.

Spurgeon no doubt had an engaging style. But he was also an authoritarian leader. Once in power, no one overruled his decisions. This was true amidst the “Down-Grade Controversy” of 1887-1888 when he, under the name of an associate, accused fellow Baptist ministers of “down grading” the faith. His own astonishing claims soon followed in his monthly magazine, The Sword and the Trowel, warning that the matter required spiritual warfare. Though failing to name names he insisted that pastors and churches connected with the Baptist Union were denying Christ’s sacrificial atonement, the inspiration of Scripture and justification by faith.

The solution was separation from those who denied the pure doctrine. Although he was essentially a lone ranger, he wielded power due to his popularity, his name recognition and church size. His accusations, according to an observer, “landed like a bombshell,” sending “shockwaves” among Baptists and far beyond, leaving lasting scars among Evangelicals. Even some of those who had studied at his preachers’ college were stunned by his accusations.

He was a schismatic who had simply carried his fight too far in his conviction that the heresy was bubbling up right under the surface: “How much farther could they go?,” he demanded. “What doctrine remains to be abandoned? What other truth to be the object of contempt? A new religion has been initiated, which is no more Christianity than chalk is cheese. . . . Avowed atheists are not a tenth as dangerous as those preachers who scatter doubt and stab at faith.”

Okay, Mr. Spurgeon, name these preachers. Quote them on their heresies. He had no answer. He didn’t have to. He was pompous—the Baptist Pope, some called him. He accused fellow Baptist pastors of not preaching enough gospel to save a cat. Actually, that was a clever line. I sometimes used it to rouse an otherwise distracted seminary student with this question: How much gospel does it take to save a cat? It served to liven up the student—and the rest of the class. Well, Mr. Spurgeon, how much does it take?

Late in 1887, Spurgeon announced his disassociation with the Baptist Union, and some months later the Union Council voted 95 to 5 to accept it. Spurgeon had been convinced that he would win the battle. He was popular and how could the Union go on without him? But at the end of the day, nobody won. Spurgeon had struggled with physical ailments and depression, now even more so as his preaching and reputation suffered during the final four years of his life. It was this “fight for the faith,” his wife Susannah declared, that “cost him his life.”

But in the generations since his death, Spurgeon’s name has risen higher than any other in the minds of ministers who believe that they like him must send out the alarm of heresy in the church. The issues are different, but the players—mostly megachurch pastors and seminary presidents—are similar. Thus, Beth Moore, just “Go home!” And to unnamed members of the Baptist Union, just get out!

One of the reasons that Spurgeon became so popular in the years after his death and since, was, interestingly, the power of a woman—the invalid Susannah Spurgeon. Years before he died, she had started a book and sermon fund. Church members gave liberally, and soon his books and other writings were sent to pastors all over the UK and far beyond. What she established is in some ways reminiscent of what Mark Driscoll did with his books in an effort to turn them into bestsellers. His efforts, however, were thoroughly dishonest and the whole scheme backfired. Susannah Spurgeon’s efforts did not. Her work during his lifetime and in the years after his death would do wonders into turning him into one of the most celebrated and influential preachers of all times.