By Ruth Tucker

Hymns, Hypocrites and Self-Murder

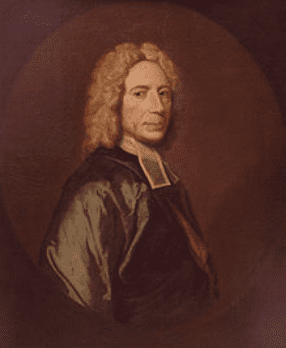

Those who have imagined he was just a hymn writer—albeit a very excellent one—are often surprised by his breadth of knowledge and wide-ranging writings. The Works of Isaac Watts (1674-1748) come in 9 volumes, the first comprised of his sermons in 773 pages. He is often called the “Father of English Hymnody,” but he was also a self-educated Renaissance man (denied an Oxford or Cambridge education due to his nonconformity).

His greatest hymn text, “O God Our Help in Ages Past” (St. Anne tune), is often sung at royal funerals and celebrations. Winston Churchill’s funeral was “magnificently choreographed,” writes Mark Tooley, with his clear specifications: “Certainly there will be lively hymns.” The first listed, “O God Our Help,” was also his hymn of choice for joint worship at a summit with FDR in 1941. Far more significant, however, are the millions of Christians worldwide who for most of three centuries have been singing Watts’ hymns in English and their native tongues. He couldn’t have known how one of those great hymns has helped tell the story:

His greatest hymn text, “O God Our Help in Ages Past” (St. Anne tune), is often sung at royal funerals and celebrations. Winston Churchill’s funeral was “magnificently choreographed,” writes Mark Tooley, with his clear specifications: “Certainly there will be lively hymns.” The first listed, “O God Our Help,” was also his hymn of choice for joint worship at a summit with FDR in 1941. Far more significant, however, are the millions of Christians worldwide who for most of three centuries have been singing Watts’ hymns in English and their native tongues. He couldn’t have known how one of those great hymns has helped tell the story:

Jesus shall reign where’er the sun

Doth his successive journeys run;

His Kingdom stretch from shore to shore,

Till moons shall wax and wane no more.

Wondering on one occasion after an extended illness if it might be time for him to call it quits, he answered: “Shall I repine then, while I survey whole nations and millions and millions of mankind that have not a thousand’s part of my blessings?”

The oldest of seven children, he was born at a time when his father was imprisoned for nonconformity. In fact, the story is told that his mother nursed him while sitting on a rock near the prison steps. When he was nine, with several siblings, his father was hauled off to prison again—enough to prompt a boy to reject nonconformity. But he was never even tempted. A precocious child, he quickly picked up languages, including Latin, Greek and Hebrew. But writing verse was his first love, a life-long activity that began well before his teen years. He complained to his father about the uninspiring church hymns and singing—”the dull indifference, the negligent and thoughtless air that sits upon the faces of a whole assembly.” His father challenged him to write a hymn the congregation could sing with enthusiasm. He did, and almost immediately people were asking for more.

But Watts’ hymns from the beginning were controversial. Indeed, the worship wars of eighteenth-century England centered around him. Proper congregational singing had been set forth by the Calvinists of Geneva—that of singing the Psalms with a limited number of tunes. Then Watts comes along with new renditions of the psalms: “Jesus shall reign,” “When I survey the wondrous cross” and many more. What! King David didn’t write those words. Heresy! Fellow minister Thomas Bradbury hissed that Watts was “profane, conceited, impudent, and . . . mangling, garbling. . . Songs of Zion” fit “for one who pays no regard to inspiration.” But within a generation many congregations were singing Watts, while essentially leaving David and the Psalms in the Hebrew Bible where they belonged.

In his early twenties, after private tutoring and studies at a small nonconformist school and after serving as an assistant pastor, Watts was called to become the full-time minister at the Mark Lane Chapel in London, using the site to train young pastors. But he struggled with health issues, sometimes bedridden with high fevers and neuralgia so serious that he lost consciousness. The congregation did not want to lose him, so another minister was called to work alongside him. Then in his early thirties, his life changed, as he later wrote: “This day thirty years I came hither to the house of my good friend Sir Thomas Abney, intending to spend but one single week under his friendly roof, and I have extended my visit to the length of exactly thirty years.” It was a beautiful rural retreat with “generosity unbounded.” Indeed, Watts had found a wealthy patron without even looking.

During these decades, Watts kept a close eye on what was going on in New England and the other colonies. He carried on years of correspondence with Cotton Mather, and was ever grateful that Ben Franklin had published his book of hymn texts. He praised the work of Edwards and Whitefield that sparked the “Great Awakening,” and back home he corresponded regularly with John Wesley and insisted that “Wrestling Jacob,” Charles Wesley’s text was better than all his own hymns combined. (Google Charles Wesley Wrestling Jacob youtube, listen to a fantastic black choir.)

Correspondence, however, filled only a small portion of Watts’ days. He spent long hours in study as well as writing essays and books that would earn him high praise as a brilliant scholar. No surprise that he was awarded honorary doctorates from both the universities of Aberdeen and Edinburgh. His expertise ranged from theology, philosophy, logic, ethics and psychology to astronomy and other fields of hard science.

Known for his quick temper and seething anger, Watts’ essays occasionally offered him opportunity to vent. In one such essay we see his exasperation with the established church. If an Anglican is guilty of lewd behavior or worse, no big deal, he sarcastically insisted. But just the opposite if the individual is a nonconformist. “What a loud clamour is raised in the town,” everyone railing “These are your nonconformists; these are your saints; These are men that pretend godliness, who do not think our church pure enough for them; See what hypocrites they are!” While skewering the established church, he did use the essay to challenge fellow nonconformists to live righteous lives. He failed , however, to adequately acknowledge the valid charge of hypocrisy.

Another instance of his venting related to those guilty of “self-murder.” He wrote a lengthy essay on the subject, with no apparent understanding of those who are tempted by, or actually commit, suicide—that, despite his study of psychology. He was certain that such was the ultimate unforgivable sin. Not only should the individual be denied Christian burial, but the civil government should revive its practice of having the individual “put into the earth with the utmost contempt.” Not in a space set aside in a cemetery, rather “in some publick cross-way, that the shame and infamy might be made known to every [passerby].” Further indignity should also be revived: “that this infamy might be lasting, they were ordained to have a stake driven through their dead bodies which was not to be removed.” Those were the good old days.

But no longer, he lamented, “‘Tis pity this practice has been omitted of late years by the too favourable sentence of their neighbours on the jury, who generally pronounce them distracted: And thus they are excused from this publick mark of abhorrence.” The neighbors on the jury, of course, were ordinary folks who had complained to officials that ones who take their own life are “distracted”—or very seriously depressed. So here is a great Christian hymn-writer penning a dreadful essay that no doubt brought even further anguish to families—to mothers—already bowed down with grief.

Fortunately, this essay did not have a long shelf-life—as did his hymn texts, including my favorite Christmas carol, “Joy to the World.” But years ago, back when I was writing Women in the Maze, I did tweak the words of the third verse: “No more let sins and sorrows grow.” Then instead of “Nor thorns infest the ground,” I inserted, “Nor rule of men abound” (picking up on another aspect of the curse). Had I expected to see this improvement indicated in new hymnbooks, I would have been sorely disappointed, though I do sing the revised words myself.