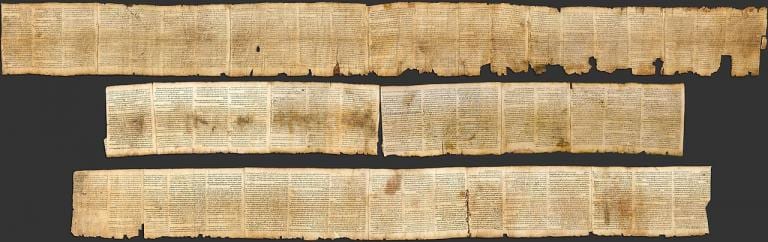

The book of Isaiah is long and complex. General consensus holds that it was compiled over time. The historical prophet Isaiah of the late 8th century BC, possibly a court prophet, was followed by others who added in the theme of his work – in the exile and post-exile. Ben Witherington III (Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics) emphasizes that this doesn’t question the prophetic nature of the book – there is predictive prophecy in all parts of the text. However, different parts of the book reflect different cultural situations. While it is wise to be cautious, unwilling to follow every whim of historical criticism, or to attach a great deal of significance to the various reconstructions proposed – there is nothing unfaithful in the suggestion that more than one ‘Isaiah’ contributed to the prophetic work recorded and compiled in this book. Nor should we find it troublesome that the whole has been woven together from pieces with scribes playing a role. The scribal community “collected, compiled, edited, and augmented all kinds of Hebrew texts including prophetic, wisdom, and legal texts.”

It seems reasonably clear that the book known as Isaiah is a compilation of prophetic texts and traditions from over several hundred years of Hebrew history, with a later prophet or prophets following in the footsteps of the historical Isaiah and drawing on various of his terms, themes, and phraseology. In other words, the later portions of the book draw on the earlier portions and amplify and augment what was said in earlier eras. (p. 44)

This doesn’t diminish or degrade the text – but it may add to our understanding of the message of the text. This is, after all, the point of reading it in the first place – as Scripture.

Witherington also points out that while Jesus read Isaiah, the people didn’t. The book of Isaiah was of unparalleled importance in the early church, but it is important to remember that most of the population was illiterate or only functionally literate. (Literacy rates were probably around 15% – but are hard to quantify). Most of the population did not have access to scrolls or the ability, time, and desire to read and study them.

Witherington also points out that while Jesus read Isaiah, the people didn’t. The book of Isaiah was of unparalleled importance in the early church, but it is important to remember that most of the population was illiterate or only functionally literate. (Literacy rates were probably around 15% – but are hard to quantify). Most of the population did not have access to scrolls or the ability, time, and desire to read and study them.

Some of the Jewish Christians may have been familiar with significant passages of the Hebrew Scriptures through regular public reading in the synagogues (something Witherington doesn’t seem to consider). Certainly I was familiar with many Biblical allusions and echoes long before I began to read the Bible seriously – from sermons and public readings. I expect the same was true in Jewish communities in the first century. Nonetheless, they did not read extensively and did not have large passages memorized. More importantly, most Gentile Christians would have very little familiarity with the OT – the Hebrew Scriptures.

While there are many echoes of Isaiah in the Gospels, most of these would likely have gone over the head of the congregation in general. “The Gospels were written for the more literate and learned members of the congregation to read out and explain to the majority of the audience where needed.” (p. 53) Later he writes about the Gospels “They are teaching and preaching tools for those not only literate, but well familiar with the OT.” (p. 54)

The net result is that the Gospels are sophisticated books designed to be read by literate readers, not by the general population of the day. Some of the echoes of the OT in the NT are subtle – not readily apparent to the casual reader. This isn’t surprising given the nature and purpose of the book. They are intended for the church as a whole, but through teachers, preachers, and readers who can answer questions and offer more detailed explanations when necessary.The primary audience was educated – and through them the broader audience of the Church heard and understood the Gospels.

We need to read Scripture in community, with specialists who study carefully and are able to explain some of the details.

But this also means that as careful readers in a 21st century literate society, we should not be surprised to find subtle allusions and echoes to the OT in the Gospels.

The Bible is a complex text … Isaiah, a community of successors, scribes and editors … down to the Gospel writers who used the OT in sophisticated ways to communicate the story of Jesus, his birth, life, death, and resurrection. There is always more to learn.

Who was the primary audience of the Gospels?

What does this mean for the way we read the texts?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

The link to the book above is a paid link. Go with this one if you prefer: Isaiah Old and New: Exegesis, Intertexutality, and Hermeneutics.