Although BioLogos and Reasons to Believe (or more accurately those Christians affiliated with these organizations) have similar views of divine action, there are significant disagreements when it comes to evolution. Chapter 7 of Old Earth or Evolutionary Creation: Discussing Origins with Reasons to Believe and BioLogos begins to address the question of evolution explicitly. Darrel Falk presents his view, representative of BioLogos, while Fazale (Fuz) Rana presents the view of Reasons to Believe. Ted Cabal, Professor of Christian Apologetics at Southern, moderates the discussion.

Although BioLogos and Reasons to Believe (or more accurately those Christians affiliated with these organizations) have similar views of divine action, there are significant disagreements when it comes to evolution. Chapter 7 of Old Earth or Evolutionary Creation: Discussing Origins with Reasons to Believe and BioLogos begins to address the question of evolution explicitly. Darrel Falk presents his view, representative of BioLogos, while Fazale (Fuz) Rana presents the view of Reasons to Believe. Ted Cabal, Professor of Christian Apologetics at Southern, moderates the discussion.

Ted opens the chapter by asking Darrel and Fuz three questions. (1) How do you define evolution? (2) How convincing do you find the evidence for common descent? And (3) Does acceptance of biological evolution necessarily entail rejection of design? These are great questions to start the conversation. Darrel and Fuz have slightly different definitions of evolution, they disagree on the evidence for common descent, but neither finds that biological evolution rules design out of the picture. Fuz, however, does think evolution raises important questions about design. More on this below.

Darrel Falk defines evolution as descent with modification. He quotes a UC Berkeley website to elaborate on this. (p. 124, http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/evo_02)

Through the process of descent with modification, the common ancestor of life on Earth gave rise to the fantastic diversity that we see documented in the fossil record and around us today. Evolution means that we’re all distant cousins: humans and oak trees, hummingbirds and whales.

Although scientists and others often move beyond science to assert that evolution disproves God, Darrel points out that there is nothing in this definition that necessarily removes God from the picture. The mechanisms of evolution include natural selection at the individual level, genetic drift, and survival of populations – even if at high cost to some individuals. Macroevolution and microevolution operate according to the same principles.

Fuz Rana looks at five kinds of evolution – microevolution, speciation, and microbial evolution are, in his words, noncontroversial. There is ample evidence that these processes have happened and are happening today. The traits of a species can change in response to external pressures. Darrel mentions lactose tolerance in humans. Such changes represents microevolution. Speciation occurs when one species gives rise to two or more sister species – different species of finches, for example. Microbial evolution includes such developments as antibiotic resistance or the ability to digest synthetic fabrics. Fuz notes that “microbial evolution is not surprising given the large microbial population sizes.” (p. 131)

Fuz finds far less support for two additional kinds of evolution – chemical evolution (i.e. abiogenesis and the origin of life) and macroevolution (the origin of life’s major groups from a common ancestor). With respect to the first, Darrel responds, and I agree, that questions surrounding the origin of life fall outside the scope of biological evolution. Evolution, descent with modification, describes the progression in the diversity of life from a common ancestor. Darrel and Fuz disagree quite strongly when it comes to macroevolution. Although significant questions remain, Darrel finds the evidence convincing while Fuz does not.

The arguments advanced by Fuz are worth looking at more closely.

Before digging into the scientific evidence he begins by outlining a few philosophical and theological concerns with evolution. First, from his debates with atheists he notes that “to make a case for a Creator and the Christian faith, it is incumbent on us to (1) distinguish our models from those that are materialistic and (2) identify places where God has intervened in life’s history. If we cannot, it is hard to convince skeptics that a Creator exists.” (p. 129) Second, he feels that common descent disagrees with the biblical accounts of creation. The active verbs in Genesis 1 and 2 “imply that God took a direct and personal role and did not just oversee a process.” (p. 129) Finally, there is the question of Adam and Eve. Because descent with modification is a population level process, it calls into question the existence of a primordial couple, ancestors of the entire human race. “Giving up the historicity of Adam and Eve as humanity’s sole progenitors has wide-ranging implications for key theological doctrines.” (p. 130)

The question of Adam and Eve is one we’ve wrestled with in a number of posts – looking at arguments from a wide range of people. I am not convinced that Fuz is right about the theological importance of Adam and Eve as humanity’s sole progenitors. I find his philosophical argument centered on the apologetic values of a scientific case for a Creator more troubling. It seems to me that this leads to Christian faith built on the wrong foundation.

When Fuz digs into the scientific questions the philosophical and theological questions are always in the background. He argues that the fossil record and homologies (i.e. shared biological features) are not smoking guns in support of evolution because alternative explanations from a creation model perspective are also possible. The modifications found in the fossil record can be viewed as the progressive work of a Creator. Homologies are simply manifestations of a common blueprint to achieve the desired goal. He also argues that punctuation in the fossil record (e.g. the Cambrian Explosion) and convergence (similar structures evolving multiple times) present significant problems for macroevolution.

I find neither of his scientific arguments convincing. There is nothing in evolutionary mechanism that requires a smooth, gradual progression in the diversification of life forms. In fact, it is perfectly reasonable to find “abrupt” (on an evolutionary time scale) changes when either a barrier in possibility is overcome or a specific macroscale event occurs. I like the analogy of water filling a reservoir – when a barrier is overcome the range of possibilities can increase dramatically and descent with modification will populate the world with organisms exploiting this new range of possibilities. For example, an exoskeleton, or legs, and lungs open up possibilities that are not available to sponges or fish. Likewise a catastrophic event (e.g. a massive meteorite impact event) can open up the opportunity for a new range of structures and forms.

Convergence as an argument against evolution surprised me. Simon Conway Morris (Life’s Solution) describes convergence in detail and suggests that this demonstrates how evolution can point to design and purpose. There are a limited number of ways that certain functions can be realized. He disagrees with Stephen Jay Gould that rewinding the tape of life would results in a world foreign to our eyes. Yes there would, of course, be differences. However the same general forms would evolve again, and there is every indication that something with the same capabilities possessed by humans would again appear.

On redirect Darrel suggests that the genetic evidence for common descent is stronger than either the fossil record or homologies. Fuz counters that the strongest evidence would be in the so-called junk regions of the genome, but there is as of yet no reason to conclude that the junk doesn’t serve some function.

The later chapters in the book will dig into more of the details and in redirect Fuz refers to some of the arguments to come in these chapters. We will have to wait to evaluate the full strength of his arguments against macroevolution and common descent.

For his part, Ted Cabal comes down where I suspect that many Christians will feel the most comfortable. He feels most comfortable with the position staked out by Fuz Rana. Some of the most significant reasons are biblical and theological rather than scientific. He concludes “But I’m grateful for honest dialogue with brothers like Darrel. One great day we’ll no longer need proficiency in intramural apologetics!” (p. 141) For my part, I am grateful for the honest dialogue of Fuz Rana and Ted Cabal who, along with Darrel, model the way in which these intramural issues should be dealt with. We are all serving the same Lord even if we all hold some views that will, eventually, be proven wrong.

Do you think that Fuz Rana and Reasons to Believe are correct about the apologetic importance of this discussion?

What do you see as the strongest argument for or against macroevolution as defined by Fuz Rana?

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

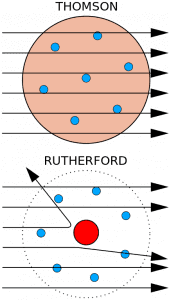

In Christian circles the analog to Rutherford’s quote is the idea that theology is the queen of the sciences. If science involves a quest for knowledge, a grand theory of everything, then theology is at the pinnacle as God is the source and center of everything that exists. More broadly, one’s worldview provides a grand unified theory of everything – thus the quest for knowledge must include or even begin with a metaphysical worldview. Thus, in some sense, theology is the queen of the sciences whether one is theist, spiritual, or atheist. We are in a quest for truth.

In Christian circles the analog to Rutherford’s quote is the idea that theology is the queen of the sciences. If science involves a quest for knowledge, a grand theory of everything, then theology is at the pinnacle as God is the source and center of everything that exists. More broadly, one’s worldview provides a grand unified theory of everything – thus the quest for knowledge must include or even begin with a metaphysical worldview. Thus, in some sense, theology is the queen of the sciences whether one is theist, spiritual, or atheist. We are in a quest for truth.