The interpretation of scripture – and especially the interpretation of the creation narratives contained in scripture – comprises one of the most significant points of conflict in the discussion of the relationship of science and the Christian faith within the church. There is a gut reaction on the part of many Christians that faith is the underdog, forced always to accommodate itself to the high priest of science. The clear, traditional reading gives way to secular reason and naturalism.

The interpretation of scripture – and especially the interpretation of the creation narratives contained in scripture – comprises one of the most significant points of conflict in the discussion of the relationship of science and the Christian faith within the church. There is a gut reaction on the part of many Christians that faith is the underdog, forced always to accommodate itself to the high priest of science. The clear, traditional reading gives way to secular reason and naturalism.

This scenario is not entirely accurate however. It is true that discoveries of science, archaeology, and geography force us, at times, to reconsider our interpretation of parts of scripture. But it is not true that there was one universal accepted interpretation prior to the modern era. The history of biblical interpretation is far more complex.

Peter Bouteneff’s book Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narratives explores the use of the creation narratives in Second Temple Judaism (ca. 200 BCE to 100 CE), in the New Testament, and in the writings of the early church fathers through the first four centuries of the church. It is a fascinating book – a bit academic, but not too strenuous a read. It is one of the most interesting and useful books I’ve read while mulling over the questions of science and Christian faith. In the first chapter of Beginnings Bouteneff discusses the development of the text of the Old Testament – especially the Septuagint (LXX) used by almost all of the NT and early Christian authors. He also explores the way that the text was used by Second Temple era Jewish authors in non-canonical writings, apocrypha and pseudepigrapha.

First: The OT canon developed slowly over the centuries before ca. 200 BCE. The various authors and editors may or may not have been familiar with the text of Genesis and the creation stories therein. There are a few clear references (Exodus 20:11 and 31:17 for example), and a few potential references – but by and large the creation narrative was not integral to the development of Israelite faith and practice. There are, of course, many references to creation in general terms to establish the sovereignty of God, but these do not use details of the creation narrative of Gen 1-3. Adam, Eve, and original sin are simply not part of the picture.

Second: The story of Adam and Eve plays an important part in the narrative logic of the Pentateuch, but not as the origin of sin in a heretofore unsullied creation. Bouteneff suggests that the linear account of creation – fall – redemption so popular today is a reading of the Pentateuch and the whole Bible that is difficult to trace before the 1700’s. A larger sense of what the editor was doing in forming the text we have today from more ancient sources will “prevent us from reading the Pentateuch (or even the whole Bible) as a linear account of “creation-fall-redemption.” He goes on:

The Pentateuch was intended to show – and this is vital if by no means novel – creation and redemption as one contiguous act. As Israel continued to see it, creation shows that God has the power to save, that creation is salvation:

Yet God my King is from of old, working salvation in the earth. You divided the sea by your might; you broke the heads of the dragons in the waters. You crushed the heads of Leviathan; you gave him as food for the creatures of the wilderness. (Ps 74:12-14)

Salvation is embedded by God in God’s act of creation, and the redemption of a particular people is universalized to encompass humankind (Gen. 12:3). (p. 8)

The creation narrative in Psalm 74 gives a picture of God conquering chaos in creation, a view at odds with the typical narrative of creation-fall-redemption. Rather than pit Psalm 74 against Genesis 1-3 they should be considered together. The logic of the narrative in Genesis, considered in the context of the Pentateuch and the OT as a whole, sees the story of Adam as a version of the story of Israel. God’s grace, salvation, and love runs through the entire narrative from Genesis through Malachi. The theme is continued in the Gospels and throughout the New Testament. Jesus came to fulfill the Law and the Prophets.

Third: The interpretation of Adam in some segments of second Temple Judaism and more significantly in the early Christian church, was influenced by the translation choices made in the LXX. As Bouteneff points out: But to translate is to interpret. Many of the choices made by the translators hinged on issues of sexuality and gender. In particular adam is a ambiguous term in the original Hebrew and the decision to translate “adam” as a generic term, humankind (άνθρωπος), or a proper name, or to use a phrase avoiding either, played a role in the later interpretations of the text. In addition word plays in the Hebrew which may modify the understanding of a particular passage, are lost in translation.

Fourth: Many Jewish texts of Second Temple Judaism reflect on the creation narrative and on Adam and Eve in particular. The way that these texts are used vary dramatically – there was no clearly agreed upon method of interpretation.

[T]he authors show themselves quite at liberty to take license with not only the purported “meaning of Genesis 1-3 but also the details of the text itself. We see especially in Jubilees, but also in other retellings of the narratives, that details are freely omitted and others added to help support the author’s agendas. This may indicate that the gradually emerging concept of “Scripture” and “canonicity” was not one that fixed a particular reading. Indeed, the authors here reviewed tacitly acknowledged multiple possibilities of meaning in the scriptural texts and dealt with them not only on the level of what might be called their “plain sense” but also on that of implied or derived meaning. (p. 25)

Philo (ca. 20 BCE – 50 CE) is a particularly interesting source. He reflects at length on the creation narratives and the 6-day creation (which he concludes is not a literal 6 days) :

Eden was not a garden that one could have walked through: “Far be it from man’s reasoning to be victim of so great impiety as to suppose that God tills the soil and plants pleasaunces” (Leg. 1.43). Likewise in Quaest. 1.8 he states that paradise was not a garden, but, rather, symbolizes “wisdom.” (p. 31)

The early interpretation of the biblical text was not a straightforward literalism, something undermined only by modern science. Nor does early interpretation uniformly describe a man Adam as the origin of sin and death. The story of the Genesis, and indeed all of the OT, was shaped and interpreted as a story of the mission of God in creation. Salvation plays a key role, but not as some “plan B” necessitated by the act of the first couple. The story of creation is the story of God’s power and purpose.

Are creation and salvation separable?

Should we think of the biblical story as a play in a series of acts (creation, fall, Israel, Jesus, Church) or as one continuous narrative of salvation?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

(A lightly edited repost.)

The presence of God is seen not in the empirical phenomena of nature, but in the purpose behind those phenomena. Thus Thomas answers objection 2:

The presence of God is seen not in the empirical phenomena of nature, but in the purpose behind those phenomena. Thus Thomas answers objection 2:

Lessons for the church. The best approach to dispel the atmosphere of conflict is to bring scientists in the church to the conversation. The scientists in the pews, known to the congregation will generally have the biggest impact. It can be useful to bring in “big names” for special lectures or presentations, but engage the locals in the conversation as experts in their fields. In the process, however, it is important to have a well-defined approach for dealing with potentially divisive issues. Ecklund describes a Scientists in Congregations program at her church – where many scientists in the congregation were initially quite wary – but overall convinced by the end that the program was a success for them personally as well as for the congregation at large. Although we have not had a formal program at our church, I have found the same to be true. To be engaged in open conversation is good for me and for my fellow Christians.

Lessons for the church. The best approach to dispel the atmosphere of conflict is to bring scientists in the church to the conversation. The scientists in the pews, known to the congregation will generally have the biggest impact. It can be useful to bring in “big names” for special lectures or presentations, but engage the locals in the conversation as experts in their fields. In the process, however, it is important to have a well-defined approach for dealing with potentially divisive issues. Ecklund describes a Scientists in Congregations program at her church – where many scientists in the congregation were initially quite wary – but overall convinced by the end that the program was a success for them personally as well as for the congregation at large. Although we have not had a formal program at our church, I have found the same to be true. To be engaged in open conversation is good for me and for my fellow Christians.

Third, the Fall was some kind of temporal event. It was historical – a movement from humanity as “good” and “righteous” to humanity as “sinful, incapable of willing the good.” In many respects, Smith bases this on the Augustinian doctrine of the Fall, affirmed in the confession and catechism. Augustine resisted any view that “would minimize the unmerited grace of God by suggesting any “inherent” human ability with respect to salvation” and “contested any teaching that would denigrate the goodness of creation.” (p. 58)

Third, the Fall was some kind of temporal event. It was historical – a movement from humanity as “good” and “righteous” to humanity as “sinful, incapable of willing the good.” In many respects, Smith bases this on the Augustinian doctrine of the Fall, affirmed in the confession and catechism. Augustine resisted any view that “would minimize the unmerited grace of God by suggesting any “inherent” human ability with respect to salvation” and “contested any teaching that would denigrate the goodness of creation.” (p. 58) 4. The tree of life and the warning about death. While there is sense of immortality attached to the tree of life, the tree in the garden is symbolic of more than just mortality and immortality. As the man and woman did not drop dead upon eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, death in this passage does not seem to refer simply to biological death. Middleton notes that the passage could refer to the introduction of mortality, but this is contradicted in Genesis and other places. Even Paul (1 Cor. 15:42-49) appears to acknowledge Adam as created mortal – of dust. Death could indicate a reversion to mortality – the man and woman must now be kept away from the tree of life. Middleton suggests, however, that life here refers more completely to human flourishing Death begins to encroach upon life when the humans turn from wisdom and obedience. Proverbs describes wisdom as “a tree of life to those who lay hold of her” (3:18) while the psalmist describes himself as “like those forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand“(88:5) because he experiences the absence of God. Death is biological and figurative at the same time. While human separation from God is a consequence of sin, the text need not imply that all death is a result of sin.

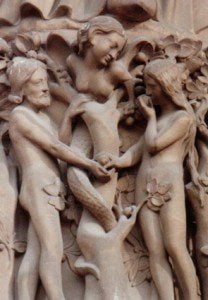

4. The tree of life and the warning about death. While there is sense of immortality attached to the tree of life, the tree in the garden is symbolic of more than just mortality and immortality. As the man and woman did not drop dead upon eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, death in this passage does not seem to refer simply to biological death. Middleton notes that the passage could refer to the introduction of mortality, but this is contradicted in Genesis and other places. Even Paul (1 Cor. 15:42-49) appears to acknowledge Adam as created mortal – of dust. Death could indicate a reversion to mortality – the man and woman must now be kept away from the tree of life. Middleton suggests, however, that life here refers more completely to human flourishing Death begins to encroach upon life when the humans turn from wisdom and obedience. Proverbs describes wisdom as “a tree of life to those who lay hold of her” (3:18) while the psalmist describes himself as “like those forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand“(88:5) because he experiences the absence of God. Death is biological and figurative at the same time. While human separation from God is a consequence of sin, the text need not imply that all death is a result of sin. 6. The snake was in the garden. The text of Genesis does not describe the snake as intrinsically evil. However, the snake is in the garden and the snake tempts the man and the woman. The snake possesses “street smarts” and there is a word play or pun in 2:25-3:1 (remember that the chapter and verse division is a much later addition). The Hebrew words for “crafty” or “shrewd” and “naked” set this up. “Here we have the identical word (ʾārûm) used with radically different meanings; the words are formally homonyms, yet they are semantically (almost) antonyms. This jarring pun signals, on the semantic level, the deception the snake will perpetuate , and its instrumentality in mediating the first sin.” (p. 86) Certainly the humans sin, but they are not the origin of sin.

6. The snake was in the garden. The text of Genesis does not describe the snake as intrinsically evil. However, the snake is in the garden and the snake tempts the man and the woman. The snake possesses “street smarts” and there is a word play or pun in 2:25-3:1 (remember that the chapter and verse division is a much later addition). The Hebrew words for “crafty” or “shrewd” and “naked” set this up. “Here we have the identical word (ʾārûm) used with radically different meanings; the words are formally homonyms, yet they are semantically (almost) antonyms. This jarring pun signals, on the semantic level, the deception the snake will perpetuate , and its instrumentality in mediating the first sin.” (p. 86) Certainly the humans sin, but they are not the origin of sin.