Hugh Ross provides a clear description of his view of old-earth progressive creation in Four Views on Creation, Evolution, and Intelligent Design. He has a high regard for the authority and inerrancy of Scripture, but this takes him in a direction quite different from that described by Ken Ham in the opening chapter. Ken Ham’s understanding of Scripture is shaped by his view of creation (perfect creation), fall, redemption and new creation. The manner in which he views this narrative and his emphasis on a young earth interpretation are internally coherent for the most part. There are some inconsistencies in Scripture (internal “problems” to be resolved), but the biggest challenge comes from modern science – physics, geology, archaeology, chemistry, biology, cosmology and linguistics for starters.

Hugh Ross provides a clear description of his view of old-earth progressive creation in Four Views on Creation, Evolution, and Intelligent Design. He has a high regard for the authority and inerrancy of Scripture, but this takes him in a direction quite different from that described by Ken Ham in the opening chapter. Ken Ham’s understanding of Scripture is shaped by his view of creation (perfect creation), fall, redemption and new creation. The manner in which he views this narrative and his emphasis on a young earth interpretation are internally coherent for the most part. There are some inconsistencies in Scripture (internal “problems” to be resolved), but the biggest challenge comes from modern science – physics, geology, archaeology, chemistry, biology, cosmology and linguistics for starters.

Hugh Ross’s view of the biblical narrative is slightly different … he sees the overarching narrative as one of preparation. God is preparing his people for the age to come. Human beings with free will, including the freedom to choose to follow God are the pinnacle and purpose of this creation. This view finds ample support in the New Testament. For example:

Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in the heavenly realms with every spiritual blessing in Christ. For he chose us in him before the creation of the world to be holy and blameless in his sight. (Eph. 1:3-4)

He has saved us and called us to a holy life—not because of anything we have done but because of his own purpose and grace. This grace was given us in Christ Jesus before the beginning of time, but it has now been revealed through the appearing of our Savior, Christ Jesus, who has destroyed death and has brought life and immortality to light through the gospel. (2 Tim. 1:9-10)

Paul, a servant of God and an apostle of Jesus Christ to further the faith of God’s elect and their knowledge of the truth that leads to godliness— in the hope of eternal life, which God, who does not lie, promised before the beginning of time. Titus 1:1-2

Ross explains:

This message implies God created the universe and all it contains for the express purpose of providing for the eternal redemption of billions of humans. Consequently day-age creationists interpret all the Bible’s creation content in the context of God’s salvific goal. We also interpret science in the context of this goal. We see every component of the universe, Earth, and life as a contributor to making possible the salvation of billions of humans. (p. 93)

There are several key points to Ross’s view.

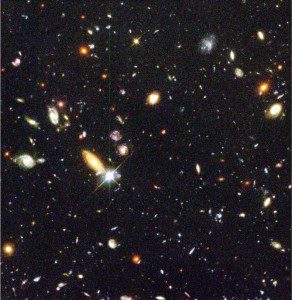

First, the earth is old because God progressively created a universe, galaxies, the sun and the earth appropriately designed for his purpose. From the creation of elements in stars to the preparation of an oxygen atmosphere on earth … think of God as a creative artist shaping the world he desired. God didn’t simply start the process and let it go, he was intimately involved at every stage.

First, the earth is old because God progressively created a universe, galaxies, the sun and the earth appropriately designed for his purpose. From the creation of elements in stars to the preparation of an oxygen atmosphere on earth … think of God as a creative artist shaping the world he desired. God didn’t simply start the process and let it go, he was intimately involved at every stage.

Second, God’s creative work ceased in the sixth “day” (actually a long period of time) with the creation of humans in his image. At this point the world was ideal for population by humans, created with a free will, to be shaped into the people God desires … not puppets but willing disciples. Each “kind” – form of life – was progressively created by God for his purposes. Ross suggests that today we see a gradual loss in diversity of life because God’s creative work has ended and progression toward maximum entropy will lead to disorder and decay. Ross also rejects the idea of common descent, taking hold of the claim in Genesis 1 that God created creature according to its kind.

Third, Adam and Eve were unique individuals – the progenitors of the entire human race – but some perhaps 135000 years ago or so early in the last ice age rather than 6000 years ago. Humans are a special creation in every sense of the word.

Fourth, Noah’s flood was a real “worldwide” event, but one that only needed to cover the area populated by humans. At this time humans were not dispersed around the globe in the Genesis narrative or in Ross’s view.

Ross suggests that both young earth creationists and evolutionary creationists leave too much to so-called “natural” processes. In particular he questions the reliance of Ham and others on the flood in shaping the earth and the manner in which rapid diversification of life post-flood is used. The old-earth progressive creation model is both more consistent with observation and emphasizes the role of God as engaged and active creator. He also suggests that evolutionary creationists err on the side of deism – with God starting the process and then stepping back and letting it go. He does acknowledge that this is not the claim of many … but the absence of a mechanism for God’s involvement he still finds troubling.

The world God created is governed by physical laws that restrain and control evil (especially natural evil) while still providing the necessary freedom for the development of humans into the people God intends for New Creation. Here it is useful to turn to the discussion in a recent post Is “Natural Evil” Evil? on the book Old-Earth or Evolutionary Creation?. Ross is more explicit in the chapter on Death, Predation and Suffering in this book where the questions are more focused and there is space for more detailed development.

While so-called natural evil is not the direct result of the fall, in creating the universe God foreknew that moral evil would enter his good creation. Consequently, he designed his creation in advance with the features to optimally deal with moral evil once it arose. The creation design had, as a necessary byproduct, the occasional occurrence of natural disasters and disease. … To summarize, in the context of God’s strategy to completely and permanently eliminate evil and suffering from his creation while enhancing the free-will capacity of redeemed humans, everything that God created is very good. (p. 83-84)

In the next post on this book we will look at the responses from Ken Ham, Deborah Haarsma, and Stephen Meyer.

What do you think of Ross’s view of the overarching narrative of scripture?

What is the overarching narrative and how does it influence our understanding of God’s creation?

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

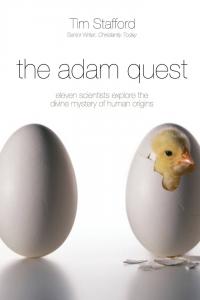

He returned to Great Britain with his wife and family after 15 years abroad. Although a non-traditional career track to be sure, he finally settled into a position at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge becoming chair of the Molecular Immunology Programme. Eventually he, along with “close Christian colleague Bob White, a professor of geophysics at Cambridge” and initial funding from the Templeton Foundation launched the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion in Cambridge. A multitude of resources are available online – including archived lectures on science and faith by a wide range of Christian speakers. He had a new mission field – to convey “the Christian message in an academically coherent manner.” (p. 164)

He returned to Great Britain with his wife and family after 15 years abroad. Although a non-traditional career track to be sure, he finally settled into a position at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge becoming chair of the Molecular Immunology Programme. Eventually he, along with “close Christian colleague Bob White, a professor of geophysics at Cambridge” and initial funding from the Templeton Foundation launched the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion in Cambridge. A multitude of resources are available online – including archived lectures on science and faith by a wide range of Christian speakers. He had a new mission field – to convey “the Christian message in an academically coherent manner.” (p. 164) In contrast to Denis Alexander, Simon Conway Morris found found Christian faith in adulthood through reading C.S. Lewis and his friends Dorothy Sayers, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield, and from a generation earlier, G. K. Chesterton. “These writers led Conway Morris to Christ. … “They opened completely new worlds. They allow[ed] us to step outside of ourselves, ask what it means to be human, why we are not animals anymore while clearly of animal derivation.” ” (p. 175)

In contrast to Denis Alexander, Simon Conway Morris found found Christian faith in adulthood through reading C.S. Lewis and his friends Dorothy Sayers, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield, and from a generation earlier, G. K. Chesterton. “These writers led Conway Morris to Christ. … “They opened completely new worlds. They allow[ed] us to step outside of ourselves, ask what it means to be human, why we are not animals anymore while clearly of animal derivation.” ” (p. 175) Stafford finishes his survey of Christians with John Polkinghorne. Another interesting story. The Rev. Dr. John Polkinghorne was born into a Christian home, regular attenders in the Anglican church. Although from a humble background, he was clearly talented in mathematics and provided with the opportunity to cultivate his ability. He studied mathematics at Trinity College in Cambridge, then pursued a Ph.D. in Physics – theoretical particle physics. He was very successful in his field. But it wasn’t enough. In his forties he left academic science (he was now a Professor at Cambridge) and went into the ministry becoming ordained in the Anglican Church. After a brief time in a rural parish he returned to Cambridge, first as dean of the chapel at Trinity Hall Cambridge and then as president of Queens. His views matured and developed during this time as did his sense of calling.

Stafford finishes his survey of Christians with John Polkinghorne. Another interesting story. The Rev. Dr. John Polkinghorne was born into a Christian home, regular attenders in the Anglican church. Although from a humble background, he was clearly talented in mathematics and provided with the opportunity to cultivate his ability. He studied mathematics at Trinity College in Cambridge, then pursued a Ph.D. in Physics – theoretical particle physics. He was very successful in his field. But it wasn’t enough. In his forties he left academic science (he was now a Professor at Cambridge) and went into the ministry becoming ordained in the Anglican Church. After a brief time in a rural parish he returned to Cambridge, first as dean of the chapel at Trinity Hall Cambridge and then as president of Queens. His views matured and developed during this time as did his sense of calling.