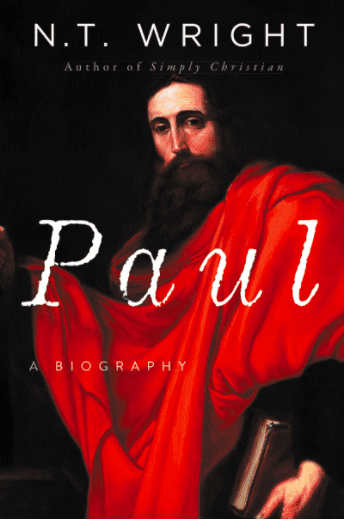

N.T. Wright’s big book on Jesus called Jesus and the Victory of God was turned into a more accessible book when he wrote The Challenge of Jesus and then later Simply Jesus, so when he wrote Paul and the Faithfulness of God many of us expected something similar: The Challenge of Paul or a Simply Paul. But that’s not what he’s done. His newest (and soon to be released) book is called Paul: A Biography and it is not an accessible version of Paul and the Faithfulness of God but something altogether different: a biography.

N.T. Wright’s big book on Jesus called Jesus and the Victory of God was turned into a more accessible book when he wrote The Challenge of Jesus and then later Simply Jesus, so when he wrote Paul and the Faithfulness of God many of us expected something similar: The Challenge of Paul or a Simply Paul. But that’s not what he’s done. His newest (and soon to be released) book is called Paul: A Biography and it is not an accessible version of Paul and the Faithfulness of God but something altogether different: a biography.

Here we go again with another adventure through the mind of NT Wright about the mind of Paul in the world of Paul.

Here’s an opener:

An energetic and talkative man, not much to look at and from a despised race, went about from city to city talking about the One God and his “son’* Jesus, setting up small communities of people who accepted what he said and then writing letters to them, letters whose explosive charge is as fresh today as when they were first dictated. Paul might dispute the suggestion that he himself changed the world; Jesus, he would have said, had already done that. But what he said about Jesus, and about God, the world, and what it meant to be genuinely human, was creative and compelling—and controversial, in his own day and ever after. Nothing would ever be quite the same again.

Tom is always asking the bigger questions, the central questions, and these are two of them:

This raises a set of questions for any historian or would-be biographer. How did it happen? What did this busy little man have that other people didn’t? What did he think he was doing, and why was he doing it?

Why did all that change? What exactly happened on the road to Damascus?

Wright gets personal in this introduction, about his early years of learning to read Paul while still in school:

His letters existed for us in a kind of holy bubble, unaffected by the rough-and-tumble of everyday first-century life. This enabled us blithely to assume that when Paul said “justification,” he was talking about what theologians in the sixteenth century and preachers in the twentieth had been referring to by that term. It gave us license to suppose that when he called Jesus “son of God, he meant the “second person of the Trinity.” But once you say you’re looking for original meanings, you will always find surprises. History is always a matter of trying to think into the minds of people who think differently from ourselves. And ancient history in particular introduces us to some ways of thinking very different from those of the sixteenth or the twentieth century.

And what he now still believes, but it’s all the same and different:

I hasten to add that I still see Paul’s letters as part of “holy scripture.” I still think that prayer and faith are vital, nonnegotiable parts of the attempt to understand them, just as I think that learning to play the piano for oneself is an important part of trying to understand Schubert’s Impromptus. But sooner or later, as the arguments go on and people try out this or that theory, as they start reading Paul in Greek and ask what this or that Greek term meant in the first century, they discover that the greatest commentators were standing on the shoulders of ancient historians and particularly lexicographers, and they come, by whatever route, to the questions of this book: who Paul really was, what he thought he was doing, why it “worked,” and, within that, what the nature of the transformation he underwent on the road to Damascus was.

As always, Wright’s concern is history and a historical perspective, a Paul in his own time:

Once we get clear about this, we gain a “historical” perspective in three different senses. First, we begin to see that it matters to try to find out what the first-century Paul was actually talking about over against what later theologians and preachers have assumed he was talking about….

Second, when we start to appreciate “what Paul was really talking about,” we find that he was himself talking about “history” in the sense of “what happens in the real world,” the world of space, time, and matter.

Third, therefore, as far as Paul was concerned, his own “historical” context and setting mattered. The world he lived in was the world into which the gospel had burst, the world that the gospel was challenging, the world it would transform.

This will become a standard textbook on the life of Paul, mark my word.