In what will become one of the most discussed chapters in Greg Boyd’s The Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Boyd sketches The Synthesis Solution. That is, four ways the church has attempted to include the violence passages in its theology without diminishing its view of Scriptures.

In what will become one of the most discussed chapters in Greg Boyd’s The Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Boyd sketches The Synthesis Solution. That is, four ways the church has attempted to include the violence passages in its theology without diminishing its view of Scriptures.

Which of these four views did you grow up hearing? Or did you learn as the best explanation?

While theologians within the historic-orthodox church have always viewed Christ as the most important revelation of God, they have, espedaily since the fifth century, also generally assumed that the plenary inspiration of Scripture entails that the OT’s violent portraits of God must be accepted as accurate revelations alongside of Christ. Rather than seeking for ways to reinterpret the violence found in these portraits as a means of preserving a nonviolent conception of God, the way Origen, Nyssa, and others had done, these theologians sought for ways to justify the violence these portraits ascribe to God. Consequently, the dominant portrait of God advocated by the church’s major theologians over the last sixteen hundred years has been, to one degree or another, a synthesis of the portrait of God we are given in Christ and the OT’s portraits of God as a violent divine warrior. 379-80

Boyd discusses four views and finds each of the four deficient.

First, the “Beyond-Our-Categories Defense.”

The first defense of the OT’s violent depictions of God by advocates of the Synthesis Solution essentially argues that we fallen humans are in no position to question God’s actions. In this view, the transcendent and all-holy God is not subject to our fallen ethical intuitions. God’s ‘thoughts are not [our] thoughts,” and God’s “ways are not [our] ways” (Isa 55:9).3 Hence, in this view, we must simply accept that everything God is said to have done and commanded in Scripture is perfectly good, regardless of how immoral it may appear to us. 381-382

In my experience this has been a common response by my Calvinist friends, or at least the more vocal kind of Calvinist. Hence, they appeal to this text: Romans 9:14-24.

[Discussing a typical violent text] With the honesty that typified Calvin’s commentaries, as we saw in chapter 7, Calvin grants that this behavior would reflect “boundless arrogance” and be a “barbarous atrocity” if it had not been ordered by God. But since it was so ordered, according to Calvin, he concludes that we must simply accept that in this one instance at least, barbaric and atrocious-appearing behavior is, in fact, “good.” 383

A moral problem arises and it either is acknowledge or morality must be redefined.

Yet, if we must call actions “good” that we would otherwise call “evil” if God had not told us otherwise, then our calling these actions “good” cannot be motivated by any goodness we actually see in these actions or in the character of God. 384

The next two observations are potent. At least they are for me.

Related to this, unless the word “good,” when applied to God, means something analogous to what it means when we apply it elsewhere, we must accept that we have absolutely no idea what we mean when we say “God is good” or when we claim that anything God does or commands is “good.” 386

In other words, if something we would otherwise always call “evil”—such as infanticide—must be considered “good” on the grounds that God commanded it, then we have to admit that there is no longer any intelligible distinction between what we mean by “good,” when applied to God, and what we would mean by “evil” (386-7).

Second, the “Divine Punishment Defense.” I would say this is the one I grew up hearing the most, and one I encountered often in my reading into this topic.

Throughout church history, the single most common defense of God’s apparent violence in the OT has been that it expresses God’s holy wrath against sin. In this view, if God sometimes commanded or engaged in violence against people, as we find throughout the OT, it was because they deserved it. Indeed, in this view, God would be unjust if he did not punish wrongdoers. 392

Third, the “Greater Good Defense.”

When God sanctions or engages in violent behavior, this defense argues, it is to promote some greater good, or to at least prevent some greater evil. For example, the reason God commanded capital punishment for sons who were slothful and drunkards, Copan argues, is because allowing sons like this to go unpunished ‘would have had a profoundly destructive effect on the family and the wider community.” 395

Fourth, the “Progressive Revelation Explanation.”

The final primary strategy for explaining violent portraits of God in the OT by advocates of the Synthesis Solution centers on the fact that God has always had to accommodate his revelation to the limitations and fallen state of his people. His strategy was to gradually increase his people’s capacity to know him as he truly is. The revelation of God within the “God-breathed” written witness to God’s covenantal faithfulness thus unfolds gradually. 399

Throughout church history, theologians have explained embarrassing or troubling aspects of the way God is depicted in Scripture by claiming that these depictions do not reflect the way God actually is; they rather reflect the way God had to adjust his appearance to accommodate the limitations and fallen condition of humans. 399

Advocates of progressive revelation hold that as parents must do with children, God had to initially accommodate his revelation to the immaturity of his people, which explains why we generally find God’s revelation getting filled out, clarified, and, some would argue, corrected as the biblical narrative unfolds, culminating in the revelation of God in his incarnate Son. 400-1

Among the four versions of the Synthesis Solution that we have reviewed, I believe this approach is the most profoundly grounded in Scripture and holds the most promise as a contributing aspect of an adequate account of Scripture’s violent divine portraits. 402

Problem?

First, if God truly abhors violence and commands and engages in it merely as an accommodation to the violent proclivities of the people he is dealing with at the time, would we not expect to find Yahweh consistently discouraging violence as much as possible and commanding it and engaging in it as little as possible? 404

An even more important objection to the way progressive revelation has usually been applied is that, as we have seen is true of the other three versions of the Synthesis Solution, this view compromises the definitiveness and beauty of the revelation of the nonviolent God in the crucified Christ. 404

On the other hand, the image of the sea is often an image of chaos in scripture and in ancient Near Eastern culture more broadly. In the Genesis 1 the “deep” and the sea are inanimate objects, but remnants of this image of chaos are still present, if nothing else in the emphasis on them as inanimate objects.

On the other hand, the image of the sea is often an image of chaos in scripture and in ancient Near Eastern culture more broadly. In the Genesis 1 the “deep” and the sea are inanimate objects, but remnants of this image of chaos are still present, if nothing else in the emphasis on them as inanimate objects. The consummation in Revelation 21 begins:

The consummation in Revelation 21 begins:

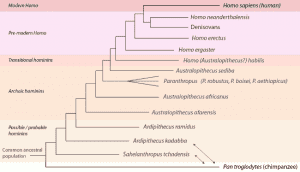

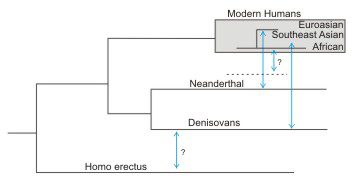

The second half of chapter three in the new book Adam and the Genome by Dennis Venema and Scot McKnight looks at the fossil and genetic evidence for human evolution. The image above, from his post at BioLogos (

The second half of chapter three in the new book Adam and the Genome by Dennis Venema and Scot McKnight looks at the fossil and genetic evidence for human evolution. The image above, from his post at BioLogos ( (2) It has been possible to sequence the genome of a few of these species including including Neanderthals and Denisovans. The analysis of genetic evidence suggests that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals to some extent and all but sub-Saharan African populations retain evidence of this interbreeding in the human genome. Humans also interbred with Denisovans in Southeast Asia and populations from Southeast Asia and Oceania retain evidence of this interbreeding. Sub-Saharan African populations may contain evidence of interbreeding with other extinct human species. Given the revolution in the ability to extract and sequence the genome of ancient specimens, we may uncover additional connections in the future.

(2) It has been possible to sequence the genome of a few of these species including including Neanderthals and Denisovans. The analysis of genetic evidence suggests that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals to some extent and all but sub-Saharan African populations retain evidence of this interbreeding in the human genome. Humans also interbred with Denisovans in Southeast Asia and populations from Southeast Asia and Oceania retain evidence of this interbreeding. Sub-Saharan African populations may contain evidence of interbreeding with other extinct human species. Given the revolution in the ability to extract and sequence the genome of ancient specimens, we may uncover additional connections in the future.