Where do women belong? Are the Mommy Wars really over? Is raising children women’s highest and most important calling? Today, Katelyn Beaty and I are conversing about all of this through her groundbreaking new book, A Woman’s Place : A Christian Vision for Your Calling in the Office, the Home and the World (Howard Books). Beaty is the former managing editor of Christianity Today and the co-founder of the award-winning Her.maneutics blog, a website covering cultural trends and theology from a Christian women’s perspective.

Where do women belong? Are the Mommy Wars really over? Is raising children women’s highest and most important calling? Today, Katelyn Beaty and I are conversing about all of this through her groundbreaking new book, A Woman’s Place : A Christian Vision for Your Calling in the Office, the Home and the World (Howard Books). Beaty is the former managing editor of Christianity Today and the co-founder of the award-winning Her.maneutics blog, a website covering cultural trends and theology from a Christian women’s perspective.

Would you give your elevator pitch for A Woman’ Place? What’s the core message of your book?

My elevator pitch takes less than 30 seconds: Women are human beings, all human beings are created to work; therefore, women are created to work.

On one level this sounds obvious. Of course women are human, and of course all women work in some capacity.

On another level, many women I’ve met—especially women in the church—face a lot of churning around their work. In some circles, there are questions about whether work done outside the home is as valuable or as eternally meaningful as work done inside of it. In other circles, there are questions about whether unpaid work is as “world-changing” as paid, professional work. There are competing messages and confusion surrounding the topic, so my book aims to give readers a strong theological and cultural foundation for wading through the tensions.

Thank you. I hate asking that question, just as I hate being asked it myself. I always want to say, “Read the book!” Because every book takes you 20,000 leagues under the sea. When you just flash a thesis, straight to the depths, people are missing out on the incredible journey that moves you to this wondrous new destination! So I want to make it clear to everyone that this is a fabulous book, full of fresh research, insights, theology, cultural analysis. And, for all of this, it’s entertaining and highly readable. So! Before we go any further, KNOW that these questions don’t replace the book in any way. I hope you’ll pick it up or buy it for your book club or small group. It will be incredibly fruitful, I promise you. Okay! Next!

Thank you. I hate asking that question, just as I hate being asked it myself. I always want to say, “Read the book!” Because every book takes you 20,000 leagues under the sea. When you just flash a thesis, straight to the depths, people are missing out on the incredible journey that moves you to this wondrous new destination! So I want to make it clear to everyone that this is a fabulous book, full of fresh research, insights, theology, cultural analysis. And, for all of this, it’s entertaining and highly readable. So! Before we go any further, KNOW that these questions don’t replace the book in any way. I hope you’ll pick it up or buy it for your book club or small group. It will be incredibly fruitful, I promise you. Okay! Next!

Some have claimed that Hillary Clinton lost primarily because she was a woman and the nation wasn’t ready yet for a female president. What’s your take on that perspective?

It’s hard to know how many Americans who voted against Clinton opposed her presidency because of her ideas and policies, or because of her gender. The truth almost certainly lies in the middle. On the one hand, there are plenty of female political leaders who those with more traditional views on gender have supported; Condoleezza Rice, Sarah Palin, and Nikki Haley are three who come to mind. That suggests that there’s openness to female political leaders with more conservative policies. On the other hand, I believe that most of us are biased to vote for people whom we like as people. It’s hard to completely separate policy from personality. On this front, many Americans found Clinton “unlikeable” or unapproachable, and part of why they found her unlikeable, I would venture, is because she does not fit traditional notions of femaleness. In many ways, she leads in stereotypically masculine ways. I believe this made a lot of Americans uncomfortable on a visceral level, and thus unlikely to support her on Election Day.

As you’ve traveled, spoken, done interviews for the book and now after its release, do you find many women identifying themselves clearly and as “egalitarian” or”complementarian,” coming from a theological perspective first, or do the various positions toward work appear to be more pragmatically based?

This is a really interesting question, because I wrote the book so that both egalitarians and complementarians could affirm the core message. I believe readers of various convictions on women’s leadership in the home and the church can nonetheless affirm the value of women’s work in professional settings. Beyond this, our views on women, and what Scripture teaches about women’s and men’s roles, don’t always neatly work themselves out in the ways we live day to day. A complementarian marriage can look very egalitarian in the daily churn. An egalitarian church, without a vision of empowering women for leadership, can look rather complementarian on Sunday morning. At some point, these labels go back to differences in scriptural interpretation, not lived experience.

That said, what we think of women’s work ultimately is rooted in what we think about women. If one believes that women are uniquely qualified or called to raise children and manage the home—or, related, that men are uniquely qualified or called to provide economically for their families—then it follows that women’s work outside the home will be valued inasmuch as it doesn’t conflict with more central work done inside the home. The Gospel Coalition gave a positive review of the book but noted that it had egalitarian underpinnings. Their reviewer, who did a wonderful, gracious job, wasn’t wrong in that interpretation.

As a single woman without children, do you find yourself readily accepted among women with children? Describe the experience of being a single woman in our family-oriented churches.

I’ve been blessed over the past several years with friendships with lots of women who have children, and I love being a part of their and their children’s lives. (Being an auntie is truly the highest vocation.) I’ve never sensed from them that not having children puts me in a different category, or means we can’t be in each other’s lives.

What happens in many local churches is more complicated and can be painful for single and/or childless women. I share a story in the book of finding myself in a circle of women after church one Sunday two years ago, and of the seven women, three were pregnant. Naturally the conversation went to having children and pregnancy, and unfortunately there was no attempt made to find a topic that all of us could talk about. What happened that morning, I think, is emblematic of what happens for many single women in the local church, especially in suburban settings. It’s not that anyone explicitly intends to exclude women without children. It’s that the programming and messages for women so often revolve around parenting, so that women who are investing a majority of their lives in professional work, often through no choice of their own, wonder where they fit. This is compounded when faith-and-work resources are tied to the men’s ministry—it communicates that women aren’t working outside the home or that professional work is uniquely a man’s thing. Raising children is a beautiful and crucial kind of work. Work is a topic that all Christians can engage, and it’s a topic that extends naturally to those without spouses or children.

In my myths of parenting book, I challenged some of the notions about parenting that are still prevalent, that women’s primary contribution to the kingdom of God is through raising godly children. When the kids “turn out” well, your life’s work has been a success. Of course, if your kids turn aside in any way, you’ve failed in your primary mission. This perspective is in step, of course, with our whole outcomes-based educational system. But you’ve got some really terrific news for mothers laboring under this impossible weight. Would you speak to that?

Any wisdom I’ve gleaned on this topic has come from conversations with women raising children. One thing I’ve observed among them is that whether or not a mother works outside the home is not a predictor of how a child will “turn out.” I think of adult friends whose fathers had passed away and whose mothers had to work to make ends meet. Or friends whose moms were simply invested in their careers and who were away from home during the day while the children were growing up. There’s no sign that these friends turned out much differently from friends whose moms were full-time at home. What matters is love, nurture, affection, attention, education, and spiritual investment.

I’ve also been struck by women who have told me that they are more engaged, happier and more present when they have some professional or creative outlet outside the home, even if it’s 10-15 hours a week. Common wisdom would say that a mother has to be at home all the time for “maximum impact” on a young child’s life, but that’s not necessarily true.

We also can’t neglect the crucial role of fathers in this equation. I’m encouraged that men of my generation seem interested and highly engaged in the work of parenting and home management. Women’s work outside the home necessarily affects and shapes men’s work, and I think we are culturally moving to a 50-50 model of marriage rather than a roles-based model of marriage.

As a professional woman, I’ve often felt much more comfortable in the workplace and mainstream culture than I have in churches where men, particularly older men who may not be used to working with women, didn’t quite know what to do with me. They were accustomed to women who worked at home and who were less interested in theology. I think this is changing, as more and more women attend seminary and pursue degrees in ministry and theology. But I also know there’s a lot of frustration among qualified, educated women with a heart to serve and lead, who are not given those opportunities. Could you speak to that?

We can’t be surprised that women with leadership, intellectual, and educational aspirations are turning to workplaces to find channels to express those aspirations, and to work alongside men who see them primarily as colleagues and comrades rather than as oddities or temptations. Whether or not a church or denomination ordains women to pastoral roles, what all churches can do is intentionally tap into the gifts and experiences of the women in the church for full and effective gospel witness. There are so many unseen resources and insights among half the members of any church; if church leaders can’t or won’t see those resources and insights, women will take them elsewhere. This is a great opportunity for the local church, but without the vision and intentionality among church leadership, it could easily be a missed opportunity.

How does a biblical view of feminine equality and strength differ from our mainstream cultural view?

First, I’ll say it’s hard to name one biblical view of feminine equality and strength, because there are so many models of femininity reflected in the whole of Scripture. We have the life-giving power of Eve, the shrewdness of Esther, the faithfulness of Ruth, the wisdom of Deborah, the industry of the woman of Proverbs 31, the hope of Anna, the obedience of Mary—and many more. While there are specific descriptions of women’s roles in sections of the Bible, there’s no one way to be a faithful woman of God. I find this wonderfully life-giving as a woman of God.

Having said that, feminine equality and strength in the Christian account comes ultimately from being created, known, and loved by God, not from self-will and self-determination. So ultimately we root our identity in our belovedness in God, not in whatever we can accomplish or carve out for ourselves. That’s not to say that ambition or accomplishments are bad—I devote a chapter of the book to giving women permission to pursue their ambitions. But even our ambitions find their proper source and aim in the Lord and his call upon our lives, not simply in trying to keep up with men amid their own ambitions and accomplishments.

Without a comprehensive vision of women and men flourishing alongside each other, mainstream feminism can sometimes operate on the ground as if there’s only space in the world for one sex or the other. There are only so many opportunities and invitations and opened doors, and women and men have to duke it out in order for one to get ahead. The problem that mainstream feminism is rightly addressing is that women have systemically been denied opportunity and advancement because of their sex, for a very long time. A Christian response to this reality is that sexism is sinful, plain and simple, and that workplaces and schools need to pursue more equitable cultures in which women’s gifts and talents are sought and celebrated.

That said, I believe men and women are meant to share the world, not to compete for their share of the world. Power is meant to be spent in order to empower others, not to lord it over others. Christianity provides a vision of women and men flourishing alongside each other in mutual dependence and trust. Feminist movements name a real problem on the ground; a Christian vision of reality can provide the solution.

The next section of Tim Keller’s new book

The next section of Tim Keller’s new book

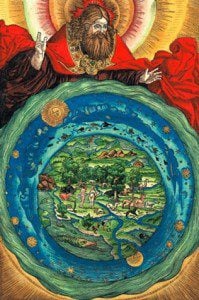

There are numerous examples of ancient cosmic geography in Job, pillars of the heavens (26:11) and of earth (9:6), storehouses of snow and hail (38:22), the chamber of the tempest (37:9) and so forth. No such reference impacts the message of the book. The purpose of the book of Job is not to describe how the cosmos works, but how God works in the cosmos. Is God just? Does the ordering of the cosmos reflect God’s justice? Does his justice shape its operation?

There are numerous examples of ancient cosmic geography in Job, pillars of the heavens (26:11) and of earth (9:6), storehouses of snow and hail (38:22), the chamber of the tempest (37:9) and so forth. No such reference impacts the message of the book. The purpose of the book of Job is not to describe how the cosmos works, but how God works in the cosmos. Is God just? Does the ordering of the cosmos reflect God’s justice? Does his justice shape its operation?