InterVarsity press recently sent me a copy of a new book A Little Book for New Scientists: Why and How to Study Science by Josh Reeves and Steve Donaldson. The book is designed for Christian college, or possibly high school, students contemplating a career in science. It also contains insights in a short readable format that pastors, including youth pastors, may find useful.

InterVarsity press recently sent me a copy of a new book A Little Book for New Scientists: Why and How to Study Science by Josh Reeves and Steve Donaldson. The book is designed for Christian college, or possibly high school, students contemplating a career in science. It also contains insights in a short readable format that pastors, including youth pastors, may find useful.

Despite the fact that I am no longer a new scientist, I immediately dove in and began to read. Josh Reeves is an assistant professor of Science and Religion at Samford University in Alabama with an undergraduate degree in Psychology, an MDiv, and a Ph.D. in Religious Studies (Science and Religion track) from Boston University. Steve Donaldson is a professor of Computer Science at Samford (BS in Physics, BS in Engineering, MS and Ph.D. in Computer Science). Both Reeves and Donaldson have long-standing interest in the questions at the forefront of science and religion, particularly science and Christianity.

I have to admit that curiosity with a touch of skepticism drove some of my interest in the book. As a scientist with now 20+ years as a professor and 30+ years as a researcher I was curious to see where I would agree or disagree with the views expressed by Reeves and Donaldson. Outside perspectives can be enlightening, but also infuriating on occasion. (Well, Reeves brings an outside perspective – Donaldson has more direct science experience.) Samford, however, has an active program in Science and Religion – and Reeves and Donaldson bring a wealth of experience to this book.

Why study science? Part one of the book addresses this basic question in three chapters. In the first, Reeves and Donaldson point to the two books metaphor “For over 1500 years, Christians have used the metaphor of God’s two books to suggest the complementarity of natural and supernatural knowledge.” (p. 22) God speaks both in the general revelation of his creation and in the special revelation to his people.

Science will not differ for the secular or religious person – not when it comes to empirical observation or mathematics. But there is a difference:

They [secular scientists] just fail to see the true spiritual significance of what they study. In other words, they do not comprehend the spiritual realities to which the physical realm bears witness, with the result that secular scientists are often wrong when they try to construct a worldview based on science. (p. 26)

The two book metaphor has limits however. These limits do not challenge the science – but point to the inability of the investigation of nature alone to bring us to a saving relationship with the Creator. Christianity is a personal and historical religion. God reveals himself through people and actions. This cannot be deduced from any kind of scientific investigation of nature. Reeves and Donaldson quote Francis Bacon who noted that creation and investigation of God’s works in creation “shows the omnipotency and wisdom of the maker, but not his image.” (p. 27) One can be a faithful Christian with no knowledge or understanding of modern science, but one cannot be a faithful Christian without the knowledge or understanding of the personal character of God and historical events transmitted down to us through the church and through Scripture.

Reeves and Donaldson next give a brief overview of the history of apparent conflict between science and the church. While the conflict is quite real on issues of metaphysical and spiritual importance, the conflict on scientific questions is overblown. Scientific materialism is at odds with Christian faith, but science itself is not. Even the famous case of Galileo needs to be understood in context – (1) Galileo was at the cutting edge and the mainstream science community (if we can push such an idea back to the time) did not accept his ideas and (2) much of the reaction was to Galileo’s rather aggressive, even offensive, method of communicating his ideas. This isn’t a simple case of science vs. the church.

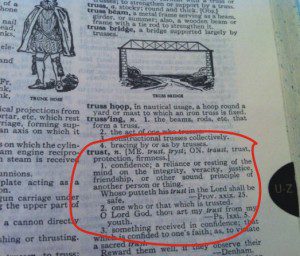

Science and ethics. The final chapter in the first section of the book looks at science and ethics (image Wikipedia). The bottom line is that we need Christians in the sciences to evaluate the claims made in the name of science and to use the knowledge obtained or obtainable through science to live out the Christian calling of love of God and love for one another.

Science and ethics. The final chapter in the first section of the book looks at science and ethics (image Wikipedia). The bottom line is that we need Christians in the sciences to evaluate the claims made in the name of science and to use the knowledge obtained or obtainable through science to live out the Christian calling of love of God and love for one another.

The title of this post comes from this section. Reeves and Donaldson claim that “there is a long history of people claiming that scientists are ethically superior to their fellow citizens.” This statement surprised me because I am not aware of anyone making this claim, nor has it cropped up in anything I’ve read. In fact, I don’t think I had ever heard the claim prior to this. Not in reading of the history of science or in the present day. It also surprised me because I know it isn’t true – all of the foibles and flaws of the general population are at play among scientists as well. Ambition … The allure of money, sex, and power runs deep. The issues are discussed in more depth in the book, but Reeves and Donaldson certainly agree that there is no ground for viewing scientists as ethically superior.

Reeves and Donaldson move from this to talk of science as a community activity. Whereas scientists as individuals are not ethically superior to other humans, could the scientific community as a whole provide an ethically superior outlook?

Our society tends to see scientists in either/or terms. Either they are especially trustworthy, playing the role of priests who can produce sacred truths for a secular society, or they are a corrupt institution because they are beholden to political pressures. A better view, as the sociologist Harry Collins has explained, is to see scientists in a middle-ground category: scientists are merely experts, and as such “should be accorded all the attention and respect we give to other experts in our society like potters, carpenters, real estate agents, and plumbers.” The main reason we trust experts is that they participate in communities that evaluate their actions. (p. 47)

The particular set of examples Collins gives here is telling (quoted approvingly it appears, by Reeves and Donaldson). Scientists are technicians producing a product or middlemen arranging a connection? And where does trust come into the mix with a potter? Potters need licenses? I could go off on a tangent – but perhaps it is better to step back and look at the bigger point. The main reason we trust scientists is that they participate in communities of experts – any new idea, insight, or result must be defended in a community of people capable of evaluating the ideas. The cutting edge should be taken with a grain of salt as the bugs haven’t necessarily been worked out – but well established theories are just that for a reason. The scientific enterprise is intrinsically a community endeavor. Ideas may start with an individual (although the reality is usually more complex than this) but they don’t stay with the individual.

But ethics is a far more embracing idea than simply judging the accuracy of answers to perplexing problems in the natural world. The scientific community places value on certain kinds of pursuits – but society at large should be involved in these discussions. How much time and money should be invested in developing better tools of war? Stand-off detection of biological and chemical threats and explosives? Drugs, imaging methods, materials, solar energy conversion, particle physics, cosmology, evolution, next generation telescopes, and a myriad of other topics? What should be the balance between basic and applied research?

In their conclusion to this section Reeves and Donaldson note that “if Christians abandon science for fear of anti-Christian bias in scientific research, it only ensures that no Christians will be left to evaluate claims made in the name of science.” (p. 54) I think it goes deeper than this – if Christians abandon science for fear of anti-Christian bias it ensures that no Christians will be at the table to challenge metaphysical claims that move beyond science, and it ensures that Christians will be missing from the table when decisions are made to value one avenue of study over another. We will benefit if Christians are active in the communities that make these decisions.

Why should Christians study science?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.