“How does your religion say you get to heaven?”

“How does your religion say you get to heaven?”

I’ve been asked that question several times, at least once in those very words. In answering, I begin by pointing out the unstated assumptions behind the question: 1) that heaven and hell are the only possible outcomes, and 2) that preparing for death is the most important aspect of religion.

Christianity (at least in its more conservative forms) is a death-preparing religion – its primary focus is on holding the proper beliefs so the follower will end up in eternal bliss and not eternal torment. Paganism (at least in its more popular forms) is a life-celebrating religion – its primary focus is on doing the right things so the follower lives meaningfully and honorably here and now. That’s a highly generalized view, and that’s certainly not all either religion is concerned with, but it is a key difference in core assumptions.

There is wisdom in focusing on living a good life here and now. This life is all we know we have with certainty. There is evidence we live on after death in one form or another – enough evidence to convince me – but there is no conclusive proof. Sacrificing the only life you know you’ve got for another life that may not even exist strikes me as a bad bet. Besides, while the world’s religions disagree on what constitutes a good life, all of them except one agree that living a good life improves your standing in the next life. Live honorably and heroically here and now and let the Gods or the Universe worry about what comes next.

Still, that’s easy for me to say. I was born into the mid-20th century American middle class. I’ve always assumed I’d live between 70 and 100 years, and while I never thought my life would be easy, I’ve never thought it would be a struggle to survive. If I had been an African slave on an American plantation, “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” would mean something very different to me. If I had been a conscript into the Roman army, knowing a violent and painful death or mutilation wasn’t just possible but likely, I might be more worried about an afterlife. If lived in any of the places and times where famine and disease run rampant and I might not live to 30, much less 70, I’d likely be more concerned with what comes after death.

It is possible to live honorably and heroically in difficult and tragic circumstances – that is, to a certain extent, the very definition of living heroically. Doing it is one thing. Having it be enough is another.

It is possible to live honorably and heroically in difficult and tragic circumstances – that is, to a certain extent, the very definition of living heroically. Doing it is one thing. Having it be enough is another.

Even living in favorable circumstances is no guarantee it will be enough. I can remember thinking about death as a child and as a young adult – I was terrified I was going to hell. I had said and done and believed all the “right” things, but the preacher talked about knowing you were going to heaven. I didn’t have the experience to realize he used knowing much more loosely than I did then, and with much less nuance than I do now.

I’ve written plenty about my journey out of fundamentalism and I don’t want to get this post sidetracked. I’ll just say I’ll never forgive Christian fundamentalism for the fear it caused me and continues to cause others.

I can remember a couple times in my 20s and 30s when I thought I might die. I wasn’t in any serious danger in any of them – they were simply unpleasant and unfamiliar circumstances mixed with a dose of paranoia. My strongest emotions were disappointment over the things I’d never get to experience and regret at what I thought were bad decisions and poor priorities – regrets I later came to understand were a conflict between what I really wanted and what I’d been told I should want. I had yet to discover my True Will.

Had I died in those times, I would not have had a peaceful passing. And realizing that, I thought about death and worried about death a lot more than I wish I had.

The cold hard fact is that any of us can die at any moment, and all of us will die eventually. So while Paganism and many other religions are right to focus on celebrating this world, and while our best course of action is to focus on living honorably and heroically here and now, there is value in preparing for death.

I see three useful approaches to prepare for death.

Naturalistically. This we know – every thing that lives will some day die. That includes us. We are born, we live, we die. Why we die isn’t important – the fact is that we do, and we will. While dwelling on death is not helpful, there is no reason to fear it. Death is not “the enemy” nor is it the opposite of life. Birth is the entrance into this world and death is the entrance into whatever comes next. Just as you were fine before you were born, you’ll be fine after you die.

I had this demonstrated to me first-hand. A few years ago I had an endoscopy – they stick a camera down your throat and take pictures. Because of the gag reflex, you pretty much have to be unconscious to do it. I don’t know what anesthesia they used, but one instant I was lying on the table, wondering why the doctor was getting ready to stick the camera down my throat when I wasn’t anywhere close to going to sleep, and the next instant I was in the recovery room. No fading in and out, no dreaming, no sensations, no memory, no nothing. For those 15 – 20 minutes it was like I ceased to exist.

And it immediately occurred to me: if the atheists are right, that’s what death is like. And it’s no big deal. It’s certainly not what I want, but it’s nothing to fear. Life went on before me and life will go on after me, just as it’s done for every other creature ever born.

We prepare for death by accepting its universality and its inevitability.

Communally. If I had really died on that table my consciousness might have been extinguished but I would not have ceased to exist. I would live on in the memories of those who knew me. I would live on in the institutions I have supported and influenced – influences that will be felt long after I’m forgotten. I would live on in this blog, both in the sense that my words will be preserved and in the impact they’ve had on readers. While I have no children, I share much of my genetic makeup with my brother’s children, and I share much of my cultural and spiritual makeup with younger Pagans. I will live on in them.

Communally. If I had really died on that table my consciousness might have been extinguished but I would not have ceased to exist. I would live on in the memories of those who knew me. I would live on in the institutions I have supported and influenced – influences that will be felt long after I’m forgotten. I would live on in this blog, both in the sense that my words will be preserved and in the impact they’ve had on readers. While I have no children, I share much of my genetic makeup with my brother’s children, and I share much of my cultural and spiritual makeup with younger Pagans. I will live on in them.

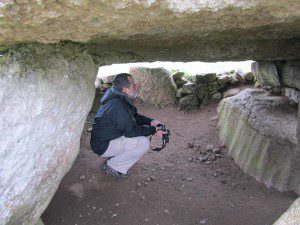

When I visited ancient tombs on my recent trip, I felt the presence of the ancestors. Not in the sense of a living person being there, nor in the sense of a ghost or spirit – I don’t think the souls of my Celtic ancestors are hanging around those places. Still, I felt them there: their lives, their loves, their hopes and dreams – those things have remained, in some cases for over 5000 years. I connected to them, and they live on in me.

The Christian theologian Paul Tillich called this “the courage to be as a part.” He said “it is the participation in something which transcends death, namely the collective, and through it, in being-itself.” (The Courage to Be, 1952)

This is a difficult concept for modern Westerners whose sense of identity rests firmly in the individual and not in the group. But it’s why warriors have always risked their lives to protect their tribes and nations, and sometimes even other tribes and other species – they know they are part of something more important and more enduring than themselves. Our pagan ancestors understood this and modern Pagans are rediscovering it – it’s why I say community is one of the centers of Paganism.

We prepare for death by participating in and contributing to communities and institutions that will live on for many generations.

Individually. For some people, accepting death and understanding communal immortality is enough. For others, the question remains: what of the afterlife, and how do we prepare for it?

I base my beliefs about the afterlife on the wisdom of many of the worlds religions, on past life memories and after death communication, and on my own religious experiences. If you don’t believe in the continuation of consciousness after death, it’s highly unlikely I’ll change your mind – and I have no need to do so. The only thing any of us can say with absolute certainty is that We Don’t Know.

How can you prepare for an afterlife if you don’t know anything about it?

Where we do not have knowledge we must have faith.

Part of this faith is the usual meaning of belief in the absence of proof: I have faith that whatever comes next will be good, whatever it is. But that doesn’t help me prepare for death – that just tells me not to fear death.

The faith we need to prepare for death is its second meaning: being faithful.

Perhaps when we die, the Valkyries will decide if we are worthy of Valhalla or if we will end up in Helheim. Perhaps Osiris will weigh our hearts against the Feather of Ma’at and decide if we will join Him in the Duat. Perhaps we will evaluate our own lives and decide what we have truly learned and what we need to do again.

Did we work on what we were supposed to do, or did we get distracted by pop culture? Did we leave the world a better place, or did we contribute to its decline? Did we do the best we could with what we had to work with? We were faithful to the calling of our Gods and ancestors?

And just what is that calling we’re supposed to be faithful to? That’s your True Will – your reason for being in this world. While you and I may share beliefs, practices, values and virtues, my True Will is not your True Will. The best I or any other person can do is point you toward a path that will help you discover what it is you’re supposed to be doing in this life. Nobody could figure that out for me, and nobody can figure it out for you.

Above the entrance to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi were the famous words γνῶθι σεαυτόν, gnōthi seauton: know thyself. That advice is as helpful in death as it is in life.

We prepare for death by doing the hard work of discerning who we are and what we are called to do, and by being faithful to that calling.

* * * * *

The Universe is so old and so long and our lives are so very brief. It is a waste to spend any of our precious hours worrying about an afterlife about which we know nothing with certainty. Instead, let us live lives of honor and heroism, and let us, in the words of Doreen Valiente, “sing, feast, dance, make music and love.”

Still, humans have wondered about death and the afterlife for at least as long as we’ve been human, and our generation is no exception. So let us also accept the inevitability of death. Let us understand that we will live on in our descendants even as our ancestors live on in us. And let us strive to know ourselves and our Great Work, and to be faithful to our calling.

It will be enough.