Honoring ancestors is a common and natural impulse across cultures and religions. It’s easily understood by most people even if they don’t actively practice it. Most adults have a grandparent, parent, or other relative they knew in this life who is now an ancestor – remembering and honoring Grandma instinctively strikes them as a good and proper thing to do. This is a point of honest commonality across many religions.

I see four categories of ancestors. We may honor them differently, but they are all worthy of our respect and devotion.

Ancestors we know

We begin by honoring the ancestors we know. These are the people we knew in life, those we’ve been told about or who we found through genealogical research. We have pictures of these ancestors, or stories about them, or a bit of biographical data. We can honor their memory because we have memories of them.

I knew my maternal grandmother very well. She came to live with us when I was 9 and lived till I was 28. I have pictures of her, but I don’t need pictures to remember her: I remember her face and her form, her voice and her hair. I remember the foods she liked to cook. Most importantly, I remember how she loved me and our whole family, and how she went out of her way to care for us, over and over and over again. I knew her well, and it’s easy for me to honor her.

My father’s family traces our history in this country through James Beckett, who was my great-great-great-grandfather. There are no pictures of him. We know he was born in Ulster around 1750, moved to North Carolina after the American Revolution, and died around 1820. That’s it. But that’s enough to honor his courage and determination to cross the ocean and provide opportunities for his descendants – opportunities that have benefitted me. I can call his name because I know his name.

Ancestors we don’t know

We knew a few ancestors in this life and we know more through history. But we all have many, many more ancestors who are beyond the reach of historical records. I know James Beckett’s name, but I have 15 other great-great-great-grandfathers and 16 great-great-great-grandmothers whose names I do not know. They are also worthy of my honor and respect.

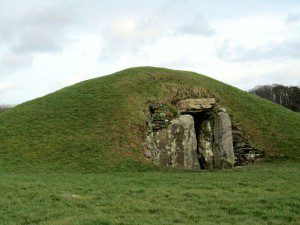

Mainstream history is helpful here. Many early immigrants to the Southeastern United States were Scots-Irish, meaning it is highly likely many more of my ancestors came here from Scotland by way of Ireland. I can visualize ancestors who were Irish, Scots, Celts, and Picts. I can go back further and further to ancestors who lived in places further south and further east, though I cannot know exactly where or when. At some point tens of thousands of years ago, I had an ancestor who walked out of Africa.

I don’t know these ancestors, but if they hadn’t lived, I wouldn’t be here. I cannot call their names – I can’t even visualize enough placeholders for all of them. But I can acknowledge their gifts and honor their lives.

When we honor these ancestors, we subtly affirm an important fact: most of them weren’t Christians. If I assume my ancestors in the British Isles converted to Christianity in 500 CE (it could have been earlier – it also could have been much later) then I’ve got about 50 generations of Christians in my heritage. While the “out of Africa” migration date is highly contentious, even using the conservative date of 70,000 years ago I’ve got about 2300 generations of non-Christian ancestors – and that’s in addition to thousands more generations of human ancestors who lived in Africa.

Yes, in leaving Christianity I have rejected the religion of some of my ancestors. But I’m working to restore the polytheist, animist, and pantheist religions of many, many more.

Ancestors of spirit

While biologically we are all related at one level or another, there are people who have influenced us to whom we are only tangentially related by blood. Some of these we knew in life: teachers, neighbors, spiritual leaders. Others we knew by their work: authors, scholars, activists. As a Druid, OBOD founder Ross Nichols is my spiritual ancestor and it is proper that I honor him, even though I never knew him and never heard of him before he died.

Because of my ancestors of blood, I have physical life. Because of my ancestors of spirit, I have spiritual and religious life. I have built my practice on the foundations laid by those who came before me.

People in other religions who are unused to ancestor work are likely to understand the importance of honoring civic heroes. We have Presidents’ Day – I’m old enough to remember when it was Washington’s birthday. We have federal holidays honoring Martin Luther King, Jr. and (for better or worse) Christopher Columbus. There are countless statues honoring war heroes, civic leaders, and sports stars… and don’t forget The Apotheosis of Washington, the painting on the rotunda of the United States Capitol Building which depicts George Washington becoming a God.

We’re all familiar with the faces on Mount Rushmore and the famous monuments in and around Washington DC, but go to any small town square and you’ll see statues of people you likely don’t know. Local ancestors are just as worthy of honor as national ancestors: they may be less-famous ancestors, but they’re our ancestors.

Ancestors most ancient

It is proper to honor our ancestors because we are in debt to them – if it weren’t for them we quite literally wouldn’t be here. Their lives and their work laid the foundations on which we build our lives.

We intuitively understand the need to honor our parents and grandparents, and it doesn’t take much thought to extend that back to the first ancestor who came to the land where we live. A little more thought brings up ancestors further and further back: those who survived war, famine, and plagues, those who crossed mountains and rivers, those who overcame constant obstacles of a life far different from our own. Keep going back and eventually you reach the first modern humans – the first of our species.

But our ancestry does not stop in East Africa 200,000 years ago. Homo erectus, Homo habilis, and Australopithecus are also our ancestors. If they were here we could not speak with them because they did not have the capacity for language (we think). But as with our more recent ancestors, if it weren’t for them we wouldn’t be here, and it is right that we honor them.

We don’t stop here, either. We have ancestors who were long-extinct mammals and even-older vertebrates. We have ancestors who were smaller and simpler creatures stretching back to the first life. Each of us must decide for ourselves how much importance we place on honoring these ancestors most ancient, but never forget they are our ancestors.

The urgent need to honor our ancestors

One of the core problems of modern society is our unwillingness to consider the needs of future generations. So what if we burn up all the oil and change the climate to something inhospitable for humans? I won’t be here – why should I care?

But when we honor our ancestors we realize we are the beneficiaries of their lives and their work. Because of them, we are here.

Because of us, future generations will be here. Will they look back on us as mighty ancestors who left them a healthy world and a thriving culture? Or will they look back on us as we look back on ancestors who owned slaves and slaughtered the buffalo?

How do you want to be remembered?

* * * * * * * * *

For a solitary ritual of communion with your ancestors, excerpt or adapt the Main Working from this Samhain ritual.

For a group ancestor ritual – particuarly with a religiously mixed group – try this Ancestor Communion Ritual we led at a Sunday service at Denton UU last year.

There are many other ways to honor and commune with your ancestors – find the one that works for you.