This is a Unitarian Universalist Sunday Service I presented twice: to Arlington UU Church on November 8, then to Pathways UU Church today. It’s an adaptation of my workshop at this year’s Pagan Unity Fest. It is not an attempt to advocate for polytheism. Rather, it’s intended to present polytheist concepts (including the fearsome Gods) to theologically diverse congregations in a way that will be meaningful to all.

This is a Unitarian Universalist Sunday Service I presented twice: to Arlington UU Church on November 8, then to Pathways UU Church today. It’s an adaptation of my workshop at this year’s Pagan Unity Fest. It is not an attempt to advocate for polytheism. Rather, it’s intended to present polytheist concepts (including the fearsome Gods) to theologically diverse congregations in a way that will be meaningful to all.

What happens after this is between the congregants and the Gods.

Introduction

I come before you this morning not as a polytheist who worships many Gods – although I am – but as a Unitarian Universalist who strongly supports every person’s right to a free and responsible search for truth and meaning. I don’t know your church well, but if you’re like most UU congregations you’ve got a collection of Christians and Buddhists, Pagans and atheists, and a lot of people who are hard to classify and damn proud of it.

Like the UU community, the Pagan community has many ideas about the Gods. There are some, particularly those from the Wiccan tradition, who worship Goddess and God. There are Pantheists who believe all is God. There are soft polytheists, who see all Gods as aspects of One God and all Goddesses as aspects of One Goddess. There are non-theists who see the Gods as metaphors or archetypes.

I’m a hard polytheist or a devotional polytheist. In my prayers, meditations, and ecstatic communions, I have experienced the Gods as real, distinct, individual beings; with Their own individual likes and dislikes, goals and dreams, and with Their own agency – They can act independently, of each other and of humans. I experience Them as individuals so I think of Them as individuals and I talk about Them as individuals… even though I know I can never be sure I’m right.

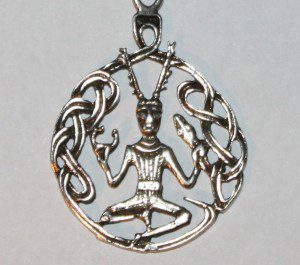

Each of you has your own beliefs and your reasons for them, but as UUs we understand that what you believe isn’t nearly as important as what you do. I wear the medallion of the Celtic God Cernunnos – the artwork is from the Gundestrup Cauldron, a silver bowl about 2200 years old, and it’s covered with mystical images of Nature. Whether you think Cernunnos is a God of Nature or an aspect of the Divine or a metaphor for Nature ultimately isn’t as important as whether you live in harmony with Nature.

Each of you has your own beliefs and your reasons for them, but as UUs we understand that what you believe isn’t nearly as important as what you do. I wear the medallion of the Celtic God Cernunnos – the artwork is from the Gundestrup Cauldron, a silver bowl about 2200 years old, and it’s covered with mystical images of Nature. Whether you think Cernunnos is a God of Nature or an aspect of the Divine or a metaphor for Nature ultimately isn’t as important as whether you live in harmony with Nature.

What is worship?

UUs have long had an uneasy relationship with worship. When I first came to Denton UU in 2003 what is now the Worship Committee was called the Program Committee, and while our fellowship was already well down the road to embracing theological and spiritual diversity, there were still a few members who didn’t want anything to do with worship. In the Pagan community, I occasionally hear someone say “I work with the Gods but I don’t worship anybody.” Perhaps we should begin by looking at what we mean by worship.

The word “worship” comes from the Old English word weorthscipe, meaning worthiness and respect. To worship is to declare something or someone worthy of honor. Contrast that simple meaning with the commonly-held idea that worship is all about self-debasement and chanting sycophantic praises to an insecure deity. Worship is a theologically neutral word.

The essence of polytheist worship is affirming that the Gods are worthy of our honor and respect. Their values and virtues are good and helpful. The natural processes They control or influence or symbolize are good even if they aren’t always nice.

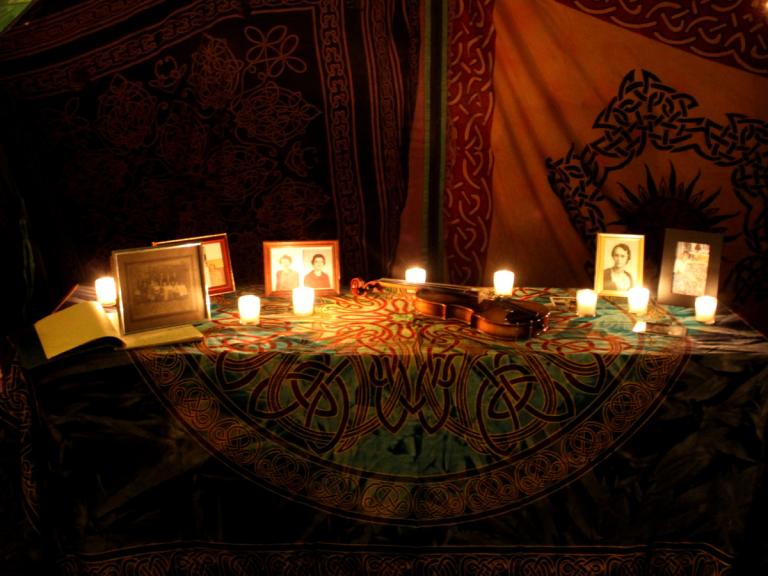

Honoring our ancestors is a common and natural impulse across cultures and religions. It’s easily understood by most people, even if they don’t practice it. Most adults have a grandparent, parent, or other relative they knew in this life who is now an ancestor – remembering and honoring Grandma instinctively strikes us as a good and proper thing to do.

The difference between honoring our ancestors and worshipping the Gods is a difference of degree, not a difference of kind. If I speak glowingly of my grandmother in a way that emphasizes her good characteristics and ignores her weaknesses, no one would think I was being anything but loving and polite. The same is true of worshipping the Gods; again, whether you see the Gods as beings or as aspects or as metaphors.

The Greek Neoplatonists taught that the immaterial Gods were so far above humans They could not be influenced by us. But they also taught that worship produces “a union of sympathetic minds.” When we worship we form a connection that flows both ways. Our thoughts and desires and devotion flow to the Gods, while the essence of Their virtues flows back to us. Worship aligns our will with the will of the Gods and gives us a glimpse into the divine perspective on Life.

Or, to quote 19th century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, “Prayer does not change God, but changes him who prays.”

How we relate to the Gods

As with Paganism, many of us come into Unitarian Universalism after spending years and years being taught there is only one God who is a stern father, obsessed with rules and quick to punish if we break them – perhaps eternally. So it’s no surprise that some of us reject the whole idea of God, while others gravitate toward the softer sides of God and others toward loving and nurturing Gods and Goddesses.

This is a necessary thing. If we are wounded we must heal, and that healing takes time – how much time varies widely from individual to individual. But a hospital is a place we go when we must – it is not a place to live our entire lives. This is true whether the hospital is literal or metaphorical – life is so much more than the hospital. Whether we see the Gods as literal or metaphorical, sooner or later we begin to understand They are far bigger and more complex than we originally thought. Eventually, we learn They are not only loving, They are also fearsome.

Some fearsome Gods

Let’s look at a few of the fearsome Gods.

Odin is first among the Gods of the Norse. His Old English name Woden gives us Wodensdag, which we know as Wednesday. Odin hung himself on Yggdrasil, the World Tree, for nine days and nine nights, and he pierced himself with his spear, all so he could learn the secrets of the runes. He plucked out one of his eyes in order to obtain wisdom. In doing so he became the most powerful of the Norse Gods.

What are you willing to do to obtain wisdom? What sacrifices will you make in order to learn what you need to learn?

The Morrigan is an Irish battle Goddess and the Chooser of the Slain. Is there one Morrigan, or three, or many? Both ancient lore and contemporary experience are unclear. Morrigan is the Lady of Sovereignty who gives the right to rule, and who demands that we rule rightly. When Her fellow Tuatha De Danann were oppressed by the Fomorians, She went to the Formorian king to “take from him the blood of his heart and the kidneys of his valor.”

The Morrigan is an Irish battle Goddess and the Chooser of the Slain. Is there one Morrigan, or three, or many? Both ancient lore and contemporary experience are unclear. Morrigan is the Lady of Sovereignty who gives the right to rule, and who demands that we rule rightly. When Her fellow Tuatha De Danann were oppressed by the Fomorians, She went to the Formorian king to “take from him the blood of his heart and the kidneys of his valor.”

What are you willing to do to reclaim your sovereignty? Are you willing to make the sacrifices necessary to live the way you’re called to live instead of the way mainstream society tells you you’re supposed to live?

Even supposedly softer Gods have fearsome sides. The Goddess Brighid is often confused and conflated with the Catholic Saint Bridget. She is one of the most beloved Goddesses in the modern Pagan world. She’s a Goddess of Healing, and a Goddess of Inspiration. But She’s also a Goddess of Smithcraft. She has a forge, and an anvil, and a hammer, where She forcefully shapes raw metal into useful tools and beautiful works of art.

Are you willing to be reshaped into an instrument of justice? Are you content to live as you are, or are you willing to be transformed, even if it’s hot, dirty, and painful?

We don’t have ancient stories about Cernunnos, but what could be more peaceful than the Lord of the Animals and the God of the Forest? Everybody knows to be afraid of lions and tigers and bears but if you get too close to an elk or a moose you can find yourself in big trouble. Just because they won’t eat you doesn’t mean they won’t kill you if they feel threatened by you.

Do you love Nature? Are you willing to care for Nature, even if it inconveniences you? Are you willing to fight for Nature against those who only see “resources” to be exploited for personal gain?

The work of fearsome Gods

It would be easy to label to fearsome Gods as evil, or at least as undesirable. It would also be wrong. The work of fearsome Gods is death, destruction, and chaos, which we generally think of as bad things.

But Gods of Death release the tired and sick and worn out to move on to the next world. Contrary to what the drug companies and the cosmetics industry try to convince us, living forever isn’t possible, not even with their overpriced anti-aging potions. And we see younger people, who, faced with painful and debilitating deaths, choose to end their lives before their suffering becomes too great. California recently became the fifth state to pass a Death With Dignity act, allowing physician assisted suicide for terminally ill patients.

Gods of Destruction tear down laws, beliefs, and institutions that no longer serve the needs of the world to make way for the new. Gods of Battle teach us to fight for our home, our tribes, and especially for justice. The crows on the battlefield disgust us, but they clean up the aftermath of wars and oppression.

There is much we can learn from fearsome Gods and their stories – not for some great hereafter, but to make us more useful for the work that needs to be done, and to build the kind of world we want and need, right here right now.

There is much we can learn from fearsome Gods and their stories – not for some great hereafter, but to make us more useful for the work that needs to be done, and to build the kind of world we want and need, right here right now.

Why should we care about fearsome Gods?

Fearsome Gods teach us the wholeness of the Gods.

When we begin exploring polytheism, many of us start with a 3-line entry on some Encyclopedia of the Gods website. As we read more about Them and begin to honor Them in ritual, we start to understand They’re more than a Goddess of Love or a Mother Goddess or a God of War. They’re more complex than that – They’re whole beings. And when we understand the wholeness of the Gods, we start to understand the wholeness of ourselves. We’re more than our job, or our families, or our health. Those things may be very valuable and meaningful parts of us, but if we lose them we are still ourselves, and we are still beings of inherent dignity and worth.

Fearsome Gods show us our place in the order of things. We used to think we were at the center of the Universe, then Copernicus showed we weren’t. We used to think we were unique among animals, then Darwin showed we weren’t. If we are unique it is because of the choices we make and not because of where we come from.

When we worship fearsome Gods we’re reminded there’s something or someone of ultimate importance… and it’s not us. Life isn’t all about us. And if it’s not all about us, we start to understand that the sovereignty of other people matters as much as our own. So does the sovereignty of other creatures and ecosystems. We start to learn that life is not about who’s on top, it’s about living in relationship with everyone and everything else.

When we worship fearsome Gods we learn to accept reality. Here in Texas we understand Spring means it’s Tornado Season.. and sometimes late Fall too. We understand a new birth is a reminder that sooner or later there will be a death. We learn that life is not simple and it’s not easy, but it’s still good. We learn to do what must be done. We don’t have to like being in a bad situation, we just have to do what we have to do to make it better.

Perhaps that means finding a new job or a new home. Perhaps it means planning a funeral and accepting that a relationship has changed from one of family member or friend to one of ancestor and beloved dead. Perhaps it means making arrangements for medical care so you won’t have to plan a funeral just yet.

Perhaps it means recognizing that economic and political power is being abused and deciding to start doing something about it.

There is much we can learn from fearsome Gods.

The wants and needs of the Gods

One of the errors that new Pagans often make is to assume that the Gods are primarily concerned with our well-being, which is assumed to coincide with our comfort and convenience. We think they’re our guardian angels or our life coaches. But whether the Gods are individual beings or if They’re the personification of ideals, They have wants and needs that do not always align with our own.

Truth is not concerned with your personal growth and development. Truth is concerned with facts, no matter how inconvenient they are. Justice is not concerned with your comfort. Justice is concerned with doing what must be done to insure the fair and equitable treatment of all.

Do the Gods need us? The Neoplatonists said the Gods need nothing. I don’t know. They certainly seem to make use of us, and that can make things difficult for us, whether we see the Gods as individual beings or as the personification of ideals.

Do the Gods need us? The Neoplatonists said the Gods need nothing. I don’t know. They certainly seem to make use of us, and that can make things difficult for us, whether we see the Gods as individual beings or as the personification of ideals.

They can call us to take on work that will turn our lives upside down. They can put us in harm’s way for reasons we may not fully comprehend. Working to make the world more just, more compassionate, more sustainable – more virtuous – is threatening to those with a vested interest in the way things are. Our fear shows we understand the potential for serving fearsome Gods.

But we do it anyway because we want to be part of something bigger than ourselves, and because we understand that anything worthwhile is going to involve work and risk.

A caveat

Worshipping fearsome Gods is a good thing, but beware apocalyptic thinking. Beware assuming the fearsome Gods are going to made a dramatic and violent appearance. For one thing, you look stupid: think of the fundamentalist Christians who predict the rapture, or worse, politicians who try to start a war in the Middle East in order bring it about.

They’re always, always wrong. Remember December 21, 2012 and the supposed end of the Mayan Calendar?

Apocalyptic thinking is wishful thinking. We think the Morrigan is going to slaughter the wicked and establish justice and everything’s going to be great… and so we don’t have to do anything. Or we think Mother Nature is going to wipe out all of humanity like the infection we are and we’re all going to die… and so we don’t have to do anything.

Apocalyptic thinking is a feature of conservative monotheism – it’s a way to get around the philosophical dilemma of the Problem of Evil. It says the presence of evil isn’t a flaw in the character of a God who’s supposed to be both all-powerful and all good, it’s just a temporary phase in a long-term plan to make everything just fine in the end. Polytheism has no need of apocalyptic thinking – our Gods are neither all-powerful nor perfect. Good things happen, bad things happen, the Great Wheel turns and life goes on.

The fearsome Gods aren’t going to save us. Rather, They need our help to make things right.

Why worship fearsome Gods?

So with all this, and with all the long and honorable history of skepticism within Unitarian Universalism, why would anyone want to worship fearsome Gods?

We’re living in challenging times. We face climate change and resource depletion, growing wealth and income inequality, obscene amounts of student debt and the disappearance of the very jobs necessary to pay back the loans. Our police are militarized and our privacy is invaded by both governments and corporations. Even as we celebrate marriage equality we worry about the loss of reproductive freedom.

We live in fearful times – we need the support and guidance of the fearsome Gods.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said “a man will worship something … That which dominates will determine his life and character. Therefore it behooves us to be careful what we worship, for what we are worshipping we are becoming.”

Many in our mainstream society worship mindless consumption and vapid entertainment. Some worship money and power. Many worship their own egos. What are they becoming? I prefer to worship the God of the Forest, the Goddess of Sovereignty, and the Goddess of Inspiration and Transformation.

What do you want from your religion? Are you looking for opium to dull your pain? Do you want a divine vending machine where you do the “right” things and blessings just appear?

Or do you want the inspiration to live virtuously and heroically, to do what’s right even when it’s not easy, and to leave the world a better place for those who come after us?

To update the words of 19th century Episcopal minister Phillips Brooks made famous by President John F. Kennedy “Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger people.”

Worshipping fearsome Gods will make us stronger people.

Benediction

The fearsome Gods do not ask us to recite creeds but to embody Their virtues. They do not ask for flattering praise but for service to the greater good. They do not tell us everything will be OK, They show us how things really are so we can make them OK.

As we leave this sacred hour and return to the ordinary world, may the wisdom and valor of the fearsome Gods be with you and in you, both now and in the times to come.