Editors’ Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on Myth, Imagination, Fairy Tales, and Fantasy. And Faith. Read other perspectives here.

This month’s Patheos Public Square topic is “Myth, Fairy Tales, and Fantasy and the Relationship with Religion.” The writing prompt begins with “the line between legend and history can sometimes be thin.” The timing is great – I couldn’t have asked for a better example of how history has been preserved in myth than Star.Ships, which I reviewed on Tuesday. Coincidence? Remember Isaac Bonewits’ Law of Synchronicity: “coincidence is seldom mere.”

According to Nobel prize-winning author Thomas Mann, “a myth is a story about the way things never were but always are.” A myth communicates Truth about who we are, whose we are, and what’s important in life.

Fantasy, on the other hand, is a story about the way we wish things were, or they way we fear things may become if we don’t change our ways. A fairy tale may be myth or fantasy or both.

What is the place of myth and fantasy in religion?

An old joke says that if a Baptist church catches on fire, someone will make sure to save the Bible. If a Catholic church catches on fire, someone will make sure to save the host. And if a UU church catches on fire, someone will make sure to save the coffee pot. More seriously, when people are forced to leave their homes suddenly, they grab pictures, family heirlooms, and seemingly random objects.

We don’t save what’s most useful, we save what’s most meaningful to us.

We often think that if we could find the earliest versions of the stories of our ancient ancestors (or for monotheists, the original versions of their scriptures), we would have the pure truth of what happened. Surely the originals were completely factual accounts that have been bastardized and dramatized by those who appropriated them for their own selfish purposes, with no respect for the facts.

This assumes the original storytellers were most interested in preserving facts. They weren’t. They wanted to preserve something far more important – meaning.

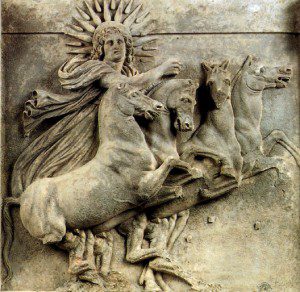

If you think the purpose of myth is to lead us to facts, you’ve missed the point. Remember, biologically and intellectually, our ancient ancestors were identical to us. Yes, every age has its dullards who take everything literally and who are only concerned what they’re having for dinner and whether or not they can get their attractive neighbor to have sex with them. But thoughtful members of ancient societies knew good and well the sun wasn’t driven across the sky in a chariot by Helios. They may not have figured out that the Earth revolves around the sun, but they did figure out the Earth is round.

Facts are good and necessary. Facts and the process by which we discover them have helped us build a world that’s richer and safer, and that allows more of us to live longer. But like having more money and things, having more facts doesn’t make our lives more meaningful. That requires myths: stories that help us understand who we are, whose we are, and what’s important in life.

The facts in myths provide context for our beliefs and practices. The facts in myths help us understand our origins. They ground us in physical places and historical times and connect us to once-living people. They remind our inner skeptics that what we’re doing is similar if not identical to what our ancestors did.

In other words, they help us answer the questions of who we are, whose we are, and what’s important in life. And occasionally, the facts in myths teach us a bit of liturgy, or a celebration, or just a piece of how our ancestors spent their days. Those facts help us adapt our own practices in ways we too may find helpful.

The purpose of myth is to teach us wisdom. I have an insatiable curiosity and I believe knowledge for the sake of knowledge is a good thing. But our contemporary society doesn’t have a shortage of knowledge, facts, and information. Our society is gorged on information, but we are starving for wisdom. Knowing “what” is useless if we can’t figure out what it means and what we’re supposed to do with it.

The story of Helios driving the sun across the sky in a chariot isn’t a case of mistaken facts. Rather, it’s a story that teaches us something of greater importance: the sun is sacred and Helios is a mighty being.

I don’t care what you think about the facts of the Gods. I have strong opinions which I frequently express, but if you think differently I won’t think less of you (so long as you don’t ridicule or needlessly confuse others). I do care what wisdom you gain through your experiences of the Gods. Does your study, worship, contemplation, and meditation of and about the Gods cause you to grow in Their virtues and values? If so, you’re a good Pagan and a good person.

I love visiting ancient sites, hearing and telling ancient stories, and learning about ancient ancestors. But the greatest value of the myths and history I learn lies in how they prepare me for my own experiences of the Gods, right here right now.