Ascendant: Modern Essays on Polytheism and Theology

edited by Michael Hardy

published by Bibliotheca Alexandrina: January 2019

166 pages

Paperback: $10.99, Kindle: $4.99

Pagans invented theology. The word itself is Greek: theos (God) + logia (the study of)… though in its original form, the first root word would have been theoi, which is plural. The first theologians (that we have records of) were Hesiod and Plato. Yet today, no less a source than Britannica.com says:

Whereas theology as a concept had its origins in the tradition of the ancient Greeks, it obtained its content and method only within Christianity. Thus, theology, because of its peculiarly Christian profile, is not readily transferable in its narrow sense to any other religion.

Certainly Christianity has built its own theological tradition based on Christian foundational assumptions. That does not mean modern polytheists should consider the field off limits to us. Quite the contrary: if our religions are to grow and thrive, they need a strong theological component. But so far we haven’t produced much in the way of theology.

This needs to change. There have been a few works of Pagan and polytheist theology, but not many, and fewer still that are accessible to ordinary readers.

As of January we have another: Ascendant: Modern Essays on Polytheism and Theology, edited by Michael Hardy and published by Bibliotheca Alexandrina. It’s a collection of short essays by modern polytheists, some well-known and others not. They vary in length and emphasis, but they’re all thought-provoking. And at this point in the polytheist restoration, thought-provoking is what we need most.

Editor Michael Hardy opens the book with an introduction titled “Theology: What It Is, Why We Need It.” He explains the task ahead of us with this:

The most obvious difference between monotheism and polytheism is the number of gods involved. But there is much more to it than that … Polytheism entails a very different way of understanding the world, and the divine. It raises its own questions that cannot be adequately addressed by answers originally developed in a monotheistic context.

One of the reasons we haven’t developed much new theology is that it hasn’t been a very high priority for us. After all, what is thinking about the Gods compared to actually experiencing the Gods for ourselves? But a deep and vibrant religion needs both. As Wayne Keysor says:

The ecstatic and the irrational works best when it is twinned with its opposite, so they might play off each other in fertile tension, drawing out insights and confusions, and pulling forth questions from the Well of Wisdom that might never have been asked otherwise.

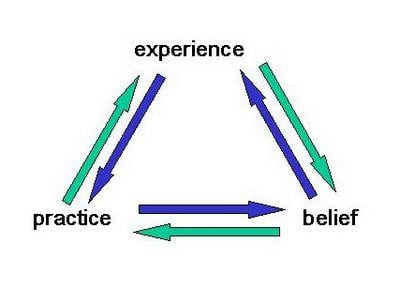

I made a similar point in The Path of Paganism when I described how experience, belief, and practice form a virtuous circle. We have an experience of the Gods, our interpretation of that experience leads us to develop beliefs about it and about the Gods, those beliefs inspire us to deeper practice, and our practice facilitates more first-hand experiences.

The last and best known form of ancient polytheist theology was Neoplatonism. Much of its literature survived to our era and some of it made its way into Christianity. That had negative repercussions, as to this day philosophy and theology that was written in a polytheist context is translated and interpreted as monotheistic – and that’s historically inaccurate.

Edward Butler, whose writing is more accessible here than in some of his articles in academic journals, says:

Nietzsche refers derisively to Christianity as “Platonism for the masses.” This would, however, be news to the polytheistic Platonists whose intellectual opposition was so vigorous in late antiquity as to require the services of the state to silence it through legislation in 529 CE. Only once the law prevented the unbaptized from public teaching did Platonism become safe for Christian appropriation.

John Michael Greer – who wrote A World Full of Gods in 2005 – does an excellent job explaining why Neoplatonism is often assumed to be monotheistic, and why that’s wrong.

The One is not a god. It does not have a spirit, a soul, or a body. It is simply the principle by which all things exist …

Since the One is not a god, has no myths, and receives no worship, it can be left to the contemplation of philosophers and mystics, while ordinary worshipers can do as polytheists have always done, and establish mutually beneficial relationship with those superlative beings we call gods.

Wayne Keysor also makes this point:

“The One” is not a god in the Jewish, Christian, or Islamic sense … rather, “the One” is completely perfect, unchanging, and fundamentally uninterested in the manifest universe, including humans. Its sole activity is contemplating the perfection of itself.

As important as Neoplatonism is, it’s not the only form of polytheist theology available to us. Gwendolyn Reece discusses the theological implications of citizenship and politics from her perspective as a modern devotee of Apollon and Athena.

The word idiot comes from an ancient Greek word for a private citizen and was applied as an insult for people who put their personal gain above the common good.

Wayne Keysor uses the problem of Gods who are said to do evil things in the stories of our ancestors to discuss different models of relationship between humans and Gods. He also reminds us that polytheism was never a unified thing in ancient times and we should not expect it to be unified today.

It is unlikely that any one theological approach will fit all. And there is no one line of reasoning that is ultimately definitive in its ability to convince everyone. This is the normal state of theology and should not be considered a failure or a defect.

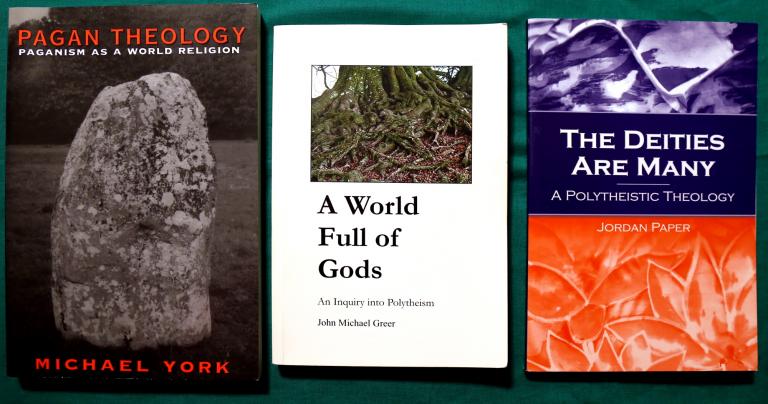

Ascendant joins a very short list of modern works of polytheist theology. In addition to A World Full of Gods, there’s Pagan Theology by Michael York (2003) and The Deities Are Many by Jordan Paper (2005). They’re all worth reading, but I consider Pagan Theology and The Deities Are Many to be religious studies more than theology.

As for me, I’m a Druid and a priest, not a theologian. But I like contemplating the Gods, and I enjoy reading other polytheists’ contemplation of Them. There is much in Ascendant I agree with, some I disagree with, and a lot I need to think about in more depth.

And that’s how theology advances. Ideas are proposed and articulated, then readers respond. Sometimes we pick up where the writers left off, while other times we think they’re wrong and argue against them.

The editor and the publisher are planning additional volumes of Ascendant in the near future. But, like all books, much of that depends on what kind of response this first volume receives. So please, contribute to the advancement of polytheist theology. Buy the book, read it, and talk about what makes an impression on you.

For those who care about such things, Michael Hardy contacted me shortly after Ascendant was published and offered to send me a review copy. He was too late – I had already ordered it. And I’ll be ordering future volumes as well.