We’ve all suffered through bad rituals at one time or another – I’ll spare you the further suffering of listing examples. But sometimes what’s even more frustrating than a bad ritual is a good ritual that’s just one thing away from being a great ritual – the kind that inspires participants to do great things and that people still talk about months and even years later.

Let’s be clear: any time we gather to honor the Gods, work magic, and celebrate being Pagan is a good time. Public ritual is not a competition. The most important part of a good ritual is the presence and participation of the Gods, and that is something we cannot control.

But we can facilitate a good experience of the Gods, of magic, and of a healthy and vibrant community. If we’re going to go to the trouble of planning, staging, and presenting a ritual, shouldn’t it be the best it can be?

I’m not talking about rituals that just aren’t your thing. As a part of a CUUPS group with a wide variety of members, I often leave a ritual thinking “that wasn’t what I would have done, but it was really good and people seemed to enjoy it.”

Rather, I’m talking about a ritual that reminds you of a soup that needed one more vegetable or a book that kept you enthralled for 300 pages and then disappointed you in the last five. It was good, but it was almost great.

When I think back on these so-close-but-not-quite rituals (some of which I wrote, to be perfectly honest) what I notice is that they were all missing essential elements. And that got me to thinking about what those essential elements (or more precisely, categories of elements) might be.

To hopefully head off needless comments that miss the point of the post, this is not some Joseph Campbell-ish attempt to universalize all Pagan rituals into one “monoritual.” Diversity is good, and if your tradition has a standard liturgy, you should follow it. Tradition is the collective wisdom of our ancestors, mainly about what works and what doesn’t.

But if you’re writing a ritual for a mixed audience like a Pagan Pride Day, a CUUPS group, or a new assortment of folks who haven’t decided what they want to be yet; and especially if you found this post by googling “Pagan ritual” I encourage you to think carefully about these eight elements.

1. Gathering

The ritual does not begin with the opening bell. The ritual begins with the arrival of the first participant.

We often think of hospitality as something we do so people will like us and say good things about us, or because it’s a virtue and a sacred obligation. More than that, though, good hospitality helps people feel comfortable and welcome, which helps them participate more fully.

What do people see and hear when they walk through the door? Does it help get them in the proper frame of mind for ritual, and especially for this ritual? Atmosphere is important.

Gathering includes what ADF calls the “pre-ritual briefing.” We need to give people the information they need to fully participate, without explaining it all in advance. Leave room for mystery.

2. Opening

A formal opening is so quick, so simple, so important… and so easy to overlook.

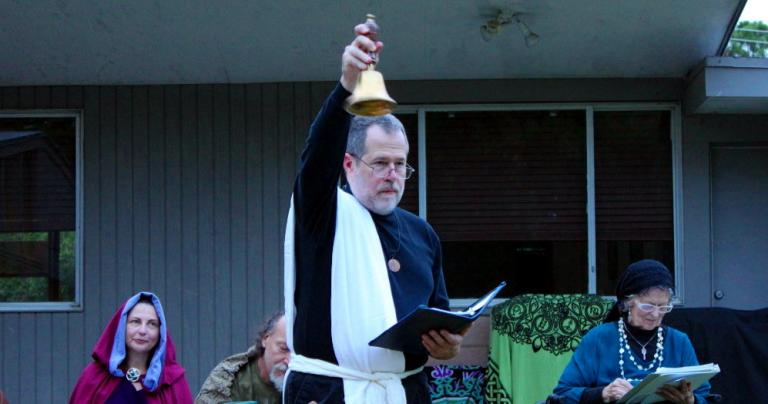

I like to use a bell for this. You can change the lighting or play a musical prelude. Merely pausing for a moment and saying the words “let us now begin” works well. You can combine it with a grounding and centering meditation, though I’ve found myself de-emphasizing opening meditations in recent years.

All participants – including the ritual leaders – need an overt signal that we are leaving ordinary time and entering sacred time.

3. Preparing the Space

If we had dedicated temples and other permanent sacred spaces, perhaps this wouldn’t be necessary. Or at least, not as necessary. But by and large, we don’t. We hold our rituals in living rooms, public parks, and UU churches. We have to turn them into temples and groves – we have to show our participants that they’re not in ordinary space anymore.

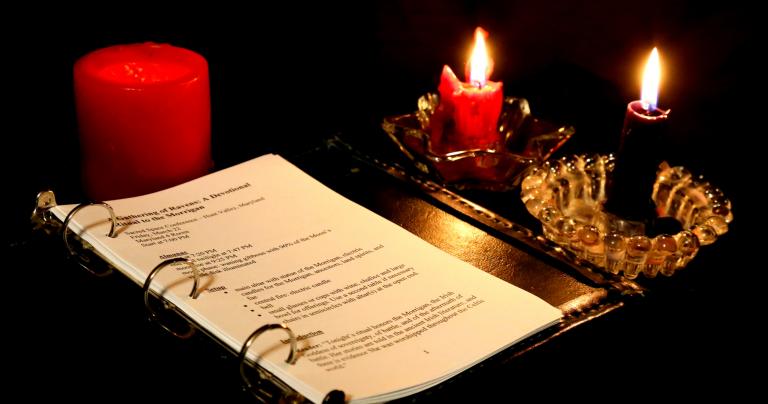

There are two parts to this. The first is physical and atmospheric. Light candles and incense, put up banners and tapestries, cover unused furniture. Cover or take down clocks – you don’t want any reminders of ordinary time. The atmosphere doesn’t have to be anachronistic (although I’m rather fond of that) it just has to be non-ordinary. Make it mysterious, but mainly, make it beautiful.

The second part is liturgical and energetic. Before we can move between the worlds, we need to ground ourselves in this world. We need to orient ourselves and affirm our relationship with the land where we are.

Some ritualists say that all Pagan ritual should begin by recreating the cosmos. This is what’s done with the Wiccan circle casting and elemental consecration, and with the ADF invocation of fire, well, and tree. I’m not going to say that’s always necessary, but I almost always do it.

Skipping this step or doing it poorly can leave participants both disconnected from the land and overly tied to the mundane world. Neither is conducive to good Pagan ritual.

4. Inviting and Welcoming

Religion is ultimately about relationships, and one of the main goals of Pagan ritual is to form and strengthen relationships with our Gods, our ancestors, and other spiritual beings.

As a polytheist, almost all the rituals I write include invitations to specific deities. Sometimes the whole purpose of the ritual is to honor and commune with Them. Other times we ask Them to attend our rite and bless it with Their presence and power. We also invite our ancestors, the spirits of the land where we are, and in some cases, the Fair Folk.

In the Gathering we provide hospitality to our physical guests. Here we provide hospitality to our spiritual guests. Greet Them with kind words and make offerings of food and drink. We may light candles or anoint statues to represent Their arrival.

If we do these four elements and do them well, we should now be ready for the main working of the ritual.

5. The Main Working

Normally this is the hardest part of composing a ritual. Most groups and traditions have a fairly standard opening and closing liturgy that can be adapted to any occasion. The hard part is coming up with what to do for this specific Samhain or Solstice or Full Moon.

But in virtually every so-close-but-so-far-away ritual, the main event has been good. Amazing, even. It’s like the leaders had this great main working and put all their time and energy into it, but then forgot to build a complete ritual around it.

This can be especially challenging when trying to revive or recreate an ancient festival. You don’t want to drop an Egyptian temple ritual into a generic Pagan liturgy, and rightly so. But that beautiful and authentic ritual someone found on a pyramid wall wasn’t done in isolation. There were preparations and purifications, gatherings and invocations. The ancients may not have used all eight of these elements, but they used some of them. Do some more research and see what else you need to make your authentic ritual complete.

Or accept the fact that you’re not an ancient Greek or a pre-Roman Celt and reimagine the rite for here and now. The idea of perfect continuity with the past is mostly a fiction, and not a very good fiction at that. A good religion is a living religion.

As always, credit your sources and don’t pretend to be something you aren’t.

Bad rituals usually have bad main workings. Could-have-been-great rituals often have good main workings but little else.

6. Regathering

The ritual isn’t over when the main working is over. If thing have gone well so far, the magic is flowing and the participants are inspired and energized. But there is still some liturgical work to do, and we need to give everyone a chance to come back to the mundane world in a soft and gradual manner.

This is where most contemporary Pagan rituals put the Simple Feast, Reversion of Offerings, or Sharing of Blessings. Those aren’t all the same things even though they often take the same form. In addition to whatever magical or divine energy they may conduct, eating and drinking helps ground people in the ordinary world.

I’m not fond of “anybody want to talk about what they just experienced?” for a variety of reasons, but in a small intimate setting it can work. If so, this is the place to put it. Poetry and music also give people a chance to come down in a good way.

Sudden stops are rarely a good thing, and the higher the high the worse the crash. Bring things down slowly and carefully.

7. Thanksgiving

Want to ruin a good ritual? Invite the Gods, experience Their blessings, and then neglect to say thank you. Or worse, “dismiss” Them… as if the Morrigan would take orders from you.

Tradition says we do not thank the Fair Folk, but we can express our gladness that they were present and that all went well.

This isn’t complicated and it need not take long. But anyone you invite should be recognized as they depart.

8. Closing

As with the opening, a formal closing can be quick and simple. But it’s just as necessary. We all need a clear signal the rite is over and we have returned to the ordinary world.

I like to end the ritual with a benediction: a brief summary and a departing blessing. But by “brief summary” I mean three or four lines, not three or four paragraphs. Trying to recap the whole thing – or worse, trying to explain it – is like a good long novel with a lousy ending.

Additional Resources

I’ve spoken rather generally about these eight categories of elements. Experienced ritualists will know what usually goes in them. If you don’t, or if you’d like some other suggestions, here are three books you may find helpful.

There’s a whole chapter on planning and facilitating rituals in my first book The Path of Paganism (2017), including an outline that can be used as a template.

The best single resource is Neopagan Rites: A Guide to Creating Public Rituals that Work by Isaac Bonewits (2007). This was originally titled Rites of Worship. That version is out of print, but Neopagan Rites is readily available.

Another good resource is The Elements of Ritual by Deborah Lipp (2003). This book deals specifically with Wiccan ritual, but it does a very good job of explaining ritual theory.