At the core of the outrage over The Return of the Pagans lies a question of definition: who is a Pagan? What is Paganism?

Language is a living thing, and appeals to the dictionary are among the weakest of arguments – originalism and textualism aren’t just bad legal theories. At the same time, not every definition is a good and useful definition.

The English word “Pagan” comes from the Latin word paganus. Most of us in the Pagan community were taught that paganus means “country dweller” and was used as a term of derision to refer to the native Britons who kept their ancestral religions instead of converting to the religion of the invading Romans.

When I wrote What Makes Paganism Pagan? in 2018, Dr. Edward Butler said we have that wrong. Paganus was a way of othering the native Britons, but the charge was not that they were country hicks. The charge was that they were following a particular religion instead of the supposedly universal religion of the Romans – and that religious othering did not begin until after the Romans converted to Christianity.

Whatever the origin, the word stuck. Then, when the British Empire expanded in the modern era, it was used as a catch-all term for any religion that was insufficiently like “proper” Anglican Christianity. Ancient Greeks and Romans were lumped in with Hindus and Buddhists and with any people still practicing their own indigenous religions. The only thing they had in common was that they were “not like us, therefore wrong and in need of correction.” And so it was perfectly good and moral to take their lands and steal their resources and treasures.

Linguistic othering is far from the British (now Anglo-American) Empire’s worst sin. At the same time, intellectual honesty and basic decency demand that we not combine people and traditions that have nothing in common other than they’re “not like us.” Calling people “Pagan” when what you really mean is “irreligious” isn’t just an insult to the Pagans (both ancient and contemporary) who were and are highly religious, it’s inaccurate.

The word “catholic” means “universal.” You’re not wrong if you use it to mean “universal” in a way that doesn’t refer to the Church of Rome (at least indirectly) but you are likely to confuse your readers. Choosing a different word would result in better communication of ideas.

Likewise, when you use “Pagan” in a way that does not refer to the pre-Christian religions of Europe and the Near East or to their contemporary re-creations and reimaginings, you may not be wrong, but there are better ways to get your message across – ways that do not needlessly antagonize those of us who follow those religions today.

The irreligious are not Pagans

In his essay in The Atlantic, David Wolpe used Donald Trump as a contemporary example of a Pagan. Trump isn’t Pagan – he’s irreligious, and highly so.

Trump claims to be a Christian and he’s very popular with certain kinds of Christians, but his life and his politics show a complete lack of understanding of religion of any kind. That doesn’t make him Pagan: he doesn’t worship Nature, or the Many Gods, or his ancestors, or pretty much anything other than himself. He’s irreligious, and those of us who disagree with him – a group that presumably includes Rabbi Wolpe – would be better served by accurately describing him as such, rather than inaccurately describing him as part of a religious tradition he does not follow.

Likewise, the bulk of those who are leaving Christianity are not becoming Pagans. I wish they were. They’re becoming “none of the above.” They’re keeping a few high-level generic beliefs and some of “cultural Christianity” but they’re not part of any group and they don’t want to be.

The irreligious, the non-religious, and the none-of-the-aboves are not Pagan. Call them what they are.

Followers of indigenous religions are not Pagans

There are still some cultures in the world that have not been wiped out by Christianity or by Islam. They’re still doing what their ancestors did for thousands of years. That doesn’t make them Pagan. It makes them Yoruba or Ojibwe or whatever they call themselves.

It took modern Pagans a while to understand that these people aren’t part of our movement, as much as we’d like to include them. There is much we can learn from indigenous people – especially about how to relate to the land – to the extent that they’re willing to share.

Likewise, there is much we can learn from Hinduism. Hinduism shares Indo-European roots with the indigenous religions of Europe, and existing Hindu practices can sometimes point us in the direction of the practices of ancient Europeans that are lost to history. But Hinduism is its own thing, and it’s not Pagan – it’s Hindu.

Satanists are not Pagans

“There’s no devil in the Craft.” So said Sandra Bullock in Practical Magic and so say most – but far from all – contemporary witches.

Satanism is not Paganism. Satanism is the inversion of Christianity. It says “your religion is so bad and so unhelpful I would rather follow your ‘adversary’ than to follow your God.” Interestingly, the largest Satanic group today – The Satanic Temple – is explicitly atheistic. They reject the idea of a literal Satan, but embrace the Satanic archetype as a way of rebelling against the repression of conservative Christianity.

I consider The Satanic Temple to be allies in the cause of religious freedom, but their anti-theism extends to polytheists – I would not be welcome in their organization and I have no intentions of joining it.

Pagans don’t agree on who is and isn’t Pagan

That’s a brief list of people who are often misidentified as Pagan. But if they aren’t Pagan, who is?

If you asked me to define Christianity, I’d talk about Jesus (but as a teacher, a God, or a sacrifice?), the Bible (but which translation? and is it inerrant and infallible?), and the myth of the Universal Church. But a simple look at the Roman Catholic Church, the Southern Baptist Convention, and the United Church of Christ shows huge differences in beliefs, spiritual practices, and in how those beliefs and practices impact the social, economic, and political actions of their followers. An outside observer would likely conclude that while these groups have a common heritage, as practiced today they are different religions.

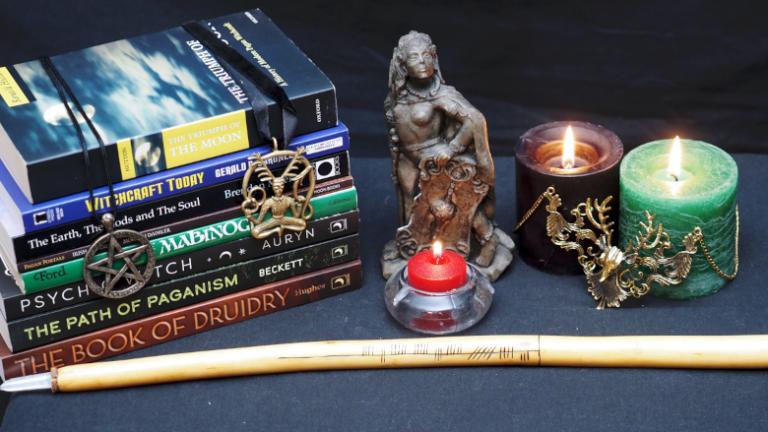

Modern Paganism is very similar. We have some commonalities but the core of what we do and who we are is different. Gardnerian Wicca, Heathenry, Kemetic Reconstructionism, and the seemingly-infinite variety of witches believe different things, do different things, and express their core values in different ways.

People get to define and identify themselves. Some people I think of as Pagans don’t use that term for themselves, and so I don’t use it for them either.

The core of my religion is polytheism – the belief in and worship of the Many Gods. Many contemporary polytheists don’t identify as Pagans. I respect that, but I do, for the reasons I outline in What Makes Paganism Pagan?

The Four Centers of Paganism

About ten years ago, several people in the wider Pagan community did some religious studies work to try to come up with a definition of Paganism. Our conclusion was that while it’s not possible to define Paganism, it is possible to describe it. Paganism is not an institution with clearly defined boundaries. Rather, it’s a movement with a center. People aren’t “in” or “out” of Paganism, they’re closer to or further away from the center.

Paganism has four centers: Nature, the Gods, the Self, and Community – places where people who go to Pagan events, read Pagan books, and generally consider themselves Pagans find the divine, however they conceive of the divine. I’m primarily a Nature-centered and Deity-centered Pagan, but there are elements of Self-centered (as in improving the self, not as in egotistical) and Community-centered Paganism in my practice as well.

We don’t hear a lot about the Four Centers anymore. That’s at least partially my fault. I’m not the primary originator of the concept (John Halstead and Joseph Bloch deserve much of that credit) but I was its loudest prophet. In recent years I’ve had other priorities. But if I’m going to argue that “Pagan” has a meaning I have an obligation to say what that meaning is. This is the best explanation I can offer.

The Big Tent of Paganism

Another model that came out of that wider conversation is the idea of the Big Tent of Paganism. As best we can remember, this term started with Jonathan Korman and was borrowed from politics, where an effective party requires people and groups with a wide variety of interests to support and elect candidates that generally share their values even if they don’t support all their goals (“politics is the art of the possible”).

Modern Paganism isn’t one religion. It’s a collection of many different religions that at least occasionally gather under a metaphorical big tent. There is no credal test to get in and you can leave any time you like. The Big Tent provides a visible, easy-to-find entry point for ordinary people who are looking for something their current religion isn’t providing. And it makes it easier for us to find others inside the tent who are doing the same things for the same reasons.

The Big Tent and the people who benefit from it (those who are inside it and those who are looking for it) are why I continue to invest time and energy advocating for the word “Pagan” and criticizing those who misuse it.

Stop using “Pagan” as a generic term for “religion that’s not like mine and therefore wrong”

I’m not claiming ownership of the word “Pagan” and I’m not insisting that people I see inside the Big Tent use it for themselves. I have neither the right nor the desire to do either.

Rather, I’m arguing that its use as a term of othering must end. Call the irreligious irreligious. Call indigenous people what they call themselves. Call Christians who leave the Church apostates until they develop a new religious identity, and then call them that.

Pagans are not beyond criticism. If you want to argue against Nature worship, against ancestor veneration, against magic, and against polytheism, have at it – that’s your right. We live in a marketplace of religions and monotheists are as entitled to promote their religions as anyone else.

What they’re not entitled to do is to misrepresent ancient traditions and modern practices because they’re not like what they believe and do.