Recently I’ve seen a “broke – woke – bespoke” meme going around about vampires being repelled by crosses and other holy objects and how that works.

The broke part says vampires are repelled by Christian symbols and elements, regardless of the faith of the person using them. “The power of Christ compels you!”

The woke part says vampires are repelled by symbols that are deeply meaningful to the person using them, if their belief is strong enough. “The power of my faith compels you!”

The bespoke part says vampires are repelled by the symbols of the religion they followed in life and that were meaningful to them. “The power of your faith compels you!”

As someone who’s a life-long vampire fan and as someone who actively works to decenter Christianity in religious discussions, I find this meme fascinating, and worth diving into more deeply.

Folklore giving way to fiction

Because I sometimes write about folkloric beings as persons, I suppose I should begin by clearly stating that the roots of vampire folklore are best understood naturalistically.

Vampire legends began because until very recently, people cared for their own dead. Someone died, the family prepared the body, laid it out for a short while, and then buried it. Figuring out exactly when someone was or wasn’t dead was a very inexact science (and it still is, though much less so than even a hundred years ago). Sometimes those thought to be dead came back – occasionally after they were already buried. Dreams of the dead returning are common – and so is the fear that they might.

The vampires of folklore were revenant corpses – something any sensible person would be frightened of and something no one would ever want to be.

And then came Dr. Polidori.

Dr. John Polidori was Lord Byron’s traveling companion in the famous “year without a summer” of 1816. The same storytelling contest that led to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein also gave us Polidori’s The Vampyre, the first modern vampire story in English. The main character was Lord Ruthven – a thinly disguised caricature of Byron – and the whole idea of vampires as evil aristocrats was born.

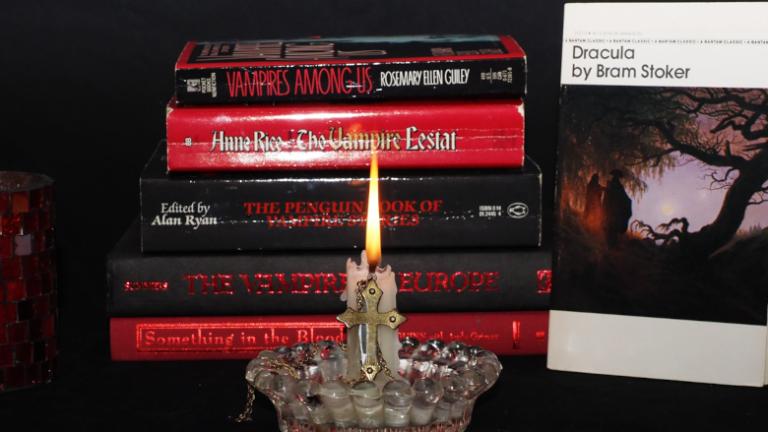

Folklore gave way to fiction, and while the vampire stories of the 19th and 20th centuries incorporated a good amount of folklore, that didn’t stop authors from Sheridan Le Fanu to Bram Stoker to Anne Rice from following in Polidori’s footsteps and creating their own visions of the undead.

Fiction in a thoroughly Christian environment

I re-read Dracula (first published in 1897) over the Winter holidays in 2022 for the first time in at least 20 years. I was struck by how Christian the story is, and not just because of things like crosses and communion wafers. Of course it is – 19th century Britain was a thoroughly Christian environment, where Christianity was presumed to be the One True Religion. The world of Dracula is a thoroughly Christian world, where Christian symbols and elements and rituals carry real power.

Stoker’s vampires are evil and so of course they’re repelled by symbols of the One True Religion. That idea carried over into the Universal movies of the 1930s and from there into the wider popular culture. “Vampires are afraid of crosses” became one of those things “everybody knows.”

Humanity, diversity, and the declining power of crosses

Countess Zaleska (played by Gloria Holden in Dracula’s Daughter in 1936) is generally considered to be the first sympathetic vampire – she wanted to be cured. The exorcism scene early in that movie is brief but excellent. And then came Barnabas Collins in Dark Shadows in 1966. They were both repelled by crosses, because that’s what the then-current ideas about vampires said should happen. But the more human vampires became, the harder it was to call them “evil.” And if a vampire isn’t truly evil, why should a symbol of good repel them?

As that was happening, Anglo-American society was becoming far less Christian. If an author doesn’t believe Christianity is the One True Religion – or if they remain Christian but don’t see any real spiritual power in Christianity – why would they make Christian symbols toxic to their characters?

So now we’re to our “woke” and “bespoke” elements. The power of holy objects lies not with any intrinsic power, but with the power of faith: either the faith of the user, or the faith of the vampire. If you believe it’s true, then for all practical purposes it’s true for you.

Which is right? It comes down to what works best for the author and their audience. But for those of us who are fascinated with such things, it makes for interesting conversation over a glass of warm red… wine.

Metaphysics – our foundational ideas

Metaphysics are our foundational ideas about the world and how it works. Those ideas form a container for interpreting our experiences, a boundary between what we assume is possible and what we assume is not. In a fictional world, the author decides the metaphysics. In the ordinary world, we have to figure them out through observations and logic, using a process that constantly tries to get closer to the Truth while accepting we will never fully get there.

Vampires and crosses are an example of metaphysical contemplation. Do crosses repel vampires? If so, why? And what are the wider implications? “Broke, woke, and bespoke” present different lines of thinking and reasoning.

Last year I taught an on-line class in Modern Pagan Metaphysics. We covered the philosophical foundations of metaphysics, and then spent five weeks going through the major foundations of modern Paganism: animism, polytheism, science, magic, and myth. And then we put all that together into a worldview that is reasonable, meaningful, and that helps us understand the world and our place in it. The class is on-demand – you can take it now if you like.

It’s important for each and every one of us to build our own metaphysics in a mindful manner. Otherwise, we end up falling back on what we were taught as small children, and on what corporate and political leaders hammer into our heads with their constant advertising.

Pagans doing Christian magic in a secular world

And now we get to the whole purpose of this post (besides the fact I can’t resist an opportunity to write about vampires).

Much of what is commonly called “folk magic” is thoroughly Christian. Preachers and priests may call it superstition (or worse, “of the devil”) but working magic is part of our legacy as humans, and people didn’t stop working magic when they became Christians. They just worked magic in a Christian environment. Your great grandma who did these things would smack you with a bible if you called her a witch.

Often, the magic worked. It still does.

And as with vampires and crosses, we wonder: how does it work? And what does it mean that it does?

Grimoire magic is religious magic

The grimoires of the medieval and early modern period are thoroughly Christian (and Jewish, which raises more metaphysical questions – as well as questions of religious authenticity). They use Christian symbols and liturgy to channel the power of the Christian God to summon demons and compel them to serve the magician.

Does that power actually come from the Christian God? Does it come from the magician themselves? Does it come from the beliefs of the demons? Or some combination of all of them?

You can do these sort of operations from a Pagan perspective, but the further away from the source tradition you get, the less likely things will work as planned.

On the other hand, some of the oldest Western magic is Pagan in origin. Or more precisely, it originated in the religious and cultural melting pot of the Eastern Mediterranean in the first couple of centuries CE. I have repaganized a couple of them, with good results.

For a good, practical look at this sort of magic from multiple perspectives, see Jason Miller’s Consorting With Spirits.

My own thinking on these things

I’m less concerned that you agree with me and more concerned that you take the time and effort to think about the deeper implications of your magic. That said, I want to share my own thinking on Pagans doing Christian magic, if only to provide a starting point for further conversations.

I am a polytheist, and as such I acknowledge the divinity, agency, and power of the Many Gods. I acknowledge the Christian God, but as one God among many, not as the only God or the supreme God.

Magic has three sources: the intercession of Gods and spirits, the manipulation of unseen forces, and psychological programming. A magician’s ability to work magic, then, depends on their ability to persuade their spiritual allies to help them, to shape and direct the currents of magic, and to perform and present their magic in ways that convince themselves and others that it is real and powerful.

A Pagan working Christian magic is unlikely to get much help from the Christian God – He is known as a jealous God. Given that few magicians working Christian magic were ever orthodox Christians (which is why the Church often harassed and sometimes burned them) you have to wonder how much the Christian God cares about orthodox Christianity, but that’s another topic for another time – and likely, for another blog.

Traditions, rituals, and objects can retain power on their own. Using them doesn’t channel power from a spirit, it draws power from the thing itself. Sometimes Pagans and secular magicians can make use of Christian items simply because they’ve got power built up in them from centuries of practice.

But I’m a Pagan and a polytheist, and I prefer to ground my magic in Paganism and polytheism.

As for vampires and crosses…

Should I ever encounter a folkloric vampire (I don’t expect to, but hey, you never know) I can promise you I won’t try to repel it with a cross. I’ll use whatever mundane weapons I have at hand to disable and dispatch it.

And should I encounter a vampire of more modern lore, I’ll trust in my own abilities with shielding and circling to remain safe… while we talk…