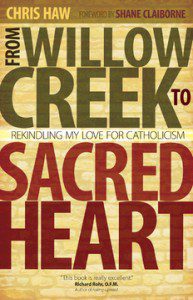

I wrote on last Friday about my friend Chris Haw and his great new book, From Willow Creek to Sacred Heart. You sent in some great questions, and we picked three winners. (Congratulations to Katie Valencia, Nick Liao, and Olivia. You copies are on the way!) Here are the winning questions, with replies from Chris.

Where do you find relevance in the Catholic Church’s message today for young Christians, especially considering the Catholic Church’s move to be what is seen and felt by many as ever more closed and defensive in its doctrine and theology rather than reflecting the inspiration of the Second Vatican Council? I am a young Catholic woman who feels continually disillusioned by my own church community. I am interested in reading your book to gain a different perspective on what has called you back to the Catholic Church community.

Where do you find relevance in the Catholic Church’s message today for young Christians, especially considering the Catholic Church’s move to be what is seen and felt by many as ever more closed and defensive in its doctrine and theology rather than reflecting the inspiration of the Second Vatican Council? I am a young Catholic woman who feels continually disillusioned by my own church community. I am interested in reading your book to gain a different perspective on what has called you back to the Catholic Church community.

I think a very patient way of engaging this problem is by precisely naming and deeply understanding what we perceive as “closed” and “defensive” in official Catholic teachings–be it in our nation’s bishops or in the global/Roman Magesterium. What exact declarations, what precise postures do we find problematic?

On a lighter example, is it the push for a closer translation of Latin in the Mass? Oddly enough, for some this is a huge bother–which to me is almost as insignificant as whether our cantor’s voice pleases me. My parish is famous for being liberal, open, and flexible; but ask them to translate a few words to make the Mass more ancient, and they become closed-minded and stubborn. Whether that’s good or bad is beside the point. I simply want to point out that even the open-minded police their boundaries. Not even liberals are exempt from conservatism; for the best liberals attempt to conserve their liberation.

I might also note, concerning this liturgy-translation problem, that it is not entirely evident to me that liturgy in the vernacular is the more “radical” or “progressive” mode. It generally feels so to me, but some things have made me wonder. 1) We all know that the “progressive” position desires diversity over uniformity; and we all know on the surface that a Latin blanket over the world appears far more uniform than, say, the Orthodox taking on the form of each nation into which it spread (Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, etc.). But a priest friend of mine, who is as progressive as the day is long, pointed out to me that the uniformity of Latin Mass has, in practice, made for a dizzying diversity of liturgy throughout the world; whereas, go anywhere in the world to an Orthodox Liturgy, and you will find startling uniformity. I personally could take either model; but I only point it out to say that the relationship between diversity and uniformity is not obvious. 2) Another liberal priest friend of mine–the kind that burned Vietnam draft cards and went to jail–says he wishes the second half of Mass, the liturgy of the Eucharist, be said in Latin. The first half in the vernacular is perfectly edifying he insists; but the symbolic structure of visiting anywhere on earth, and celebrating the Last Supper in a shared language, roots the diversity of the Church into a unity. 3) Knowing Latin would make us closer to bilingual–which seems more “liberally” educated, if nothing else. 4) All my adventurously progressive friends want more ancient, pagan, and mysterious things like dead languages in their diet. I’d rather prescribe them some ornate, byzantine, and magical Liturgy than a seeker service in English. Otherwise, they might come to the blasphemous conclusion that Christianity isn’t a complex weaving of poetry, symbol, metaphor, ritual, sacred scriptures, paradox, and mystery. Heaven forbid, they might stoop to making Christianity appear plainly relevant, straightforward, and comprehensible.

On a more serious note, some of the things that are more evidently “defensive” are the political proclamations that come out of the CDF and USCCB. A difficult one, to me, is the notion that gay marriage is destroying the family. The burden of proof, to me, is on them to demonstrate that. I understand their argument about “nature”; but even that feels a little flat to me: for, upon observing nature, it appears to be a natural occurrence that we have numerous species that are attracted to the same sex. Pulling the “Fall” card here feels like shoehorning “ought” into the “is”. Scientists would call that bending facts to suit the theory. My limited chain of logic, rather, concluded that what destroys marriage is infidelity, divorce, pre-marital sex, pornography, money problems, capitalism, cohabitation, fornication (I might even risk joining the fray and say contraception). Social science can demonstrate the correlation on almost all of those, I believe. But a group of people wishing to get married? I want to see the proof. I can applaud numerous Church leaders saying that civil unions are as far as they will go, and they support it as an issue of justice, dignity, and humans rights. (I’ve read some who actually say that.) I understand their not going farther; as they feel constrained to use a certain sacramental definition of what marriage is. But I want to start arguing when I hear the “destroying marriage” rhetoric.

Is it the abortion rhetoric? This can sometimes feel grating when injected into politics. But, I might add, that I (mostly) only register political arguments from people or groups that are actually doing something about the problem, apart from the legislation. And on that count, I think we can give the Catholics–even the insanely conservative ones–some points. The Sisters of Life, et al, should shame people of almost any political persuasion with their sacrificial commitment to care for women. And, I might add, that the Catholic Church is the only institution around, to my knowledge, that has any institutional-historical memory of the classical era of infanticide. When an institution has that much historical memory on hand–and can tell you the stories of what that was like–I think it worth at least listening. That’s “relevant” to “young people”; but none of us listen. Because we’re young people.

Women’s inclusion-issues, to me, are perhaps the most scandalous and important among these “closed” topics. The issue is too heavy to lift in what is already an oversized response. I recommend readers engage debates like the one on Commonweal (“Why Not?” a debate between Sara Butler and Robert Egan.) I also encourage readers to overlook what feel like insults and scandal, and be the more patient, engaged, theological, and steadfast party.

Speaking generally, I encourage you to do a few things (besides emailing me with further thoughts after reading my book): take encouragement that, while the Catholic Church contains a structured and formal hierarchy, it is a structure that is not without influence from the rest of its baptized members–who are also the Church themselves. Lay members kicking butt out there in the world, getting done what needs to get done, affect the atmosphere of the Church and provide a witness to others and the teaching authorities. Second, I would take the time to patiently identify and critique exact things. Some people just complain about the mere teaching authority of the church. To which I quote Chesterton, “It is rational to attack the police; nay, it is glorious. But the modern critics of [religious] authority are like people who attack the police without ever having heard of burglary.” The only thing worse than a pope is millions of popes, which is paradoxically what much of our “anti-hierarchical” modern world is constructing in its experiment of escaping religion. There are plenty of things, as stated, that even the liberals want conserved–and they reconstruct “authority” to do so. And there are plenty of things that, in order to be progressive, we might have to turn around and go the other way. Which ones? And how? Well, then we are entering into the old fashioned work of figuring things out instead of blanket statements and antagonism.

Chris, I recently read two interesting memoirs: “How to Go from Being a Good Evangelical to a Committed Catholic in Ninety-Five Difficult Steps” by Christian Smith and “Rome Sweet Home” by Scott and Kimberly Hahn –two very different books in a fast-growing genre of Protestant-to-Catholic conversion stories. Can you describe how your book fits or doesn’t fit into this genre, and what readers might be able to glean from your particular journey that may not be covered in these other conversion narratives?

I wasn’t aware that it was a fast growing genre. If anything, I’ve felt that I’m treading into a Church about which popular opinion is mostly giving up on. In my book I draw a connection between my going into Camden and my partnering with the Catholic Church–both of which are profoundly struggling, some might even say tragically living-dead. Both of which, upon entering, I felt I might be walking into a tunnel with no light at the end of it. The pedophilia scandal was raging as I entered Catholicism. Camden had entire blocks abandoned, populated with sparse dirty nomads living off crack and prostitution. Both have a feeling of near hopelessness. But Christianity taught me the odd relationship between hopelessness and hopefulness–and it takes much of my book to unpack that.

I also discuss in the book what, for me, is a very aggressive grappling with atheism. And I don’t mean, “I was once and atheist and now I believe there is a god.” Rather, at times, I view my faith through the lens of atheism. I quote Chesterton who was catching onto the deep, mysterious, “apophatic” theology implied by Christ’s cry from the cross. “In a garden Satan tempted man: and in a garden God tempted God. He passed in some superhuman manner through our human horror of pessimism. When the world shook and the sun was wiped out of heaven, it was not at the crucifixion, but at the cry from the cross: the cry which confessed that God was forsaken of God. And now let the revolutionists choose a creed from all the creeds and a god from all the gods of the world, carefully weighing all the gods of inevitable recurrence and of unalterable power. They will not find another god who has himself been in revolt. Nay, (the matter grows too difficult for human speech,) but let the atheists themselves choose a god. They will find only one divinity who ever uttered their isolation; only one religion in which God seemed for an instant to be an atheist.”

Put another way, I don’t find the Catholic Church as some neat and happy answer to life’s problems; I see it through what sometimes feels like the other side of the apocalypse in Camden. I don’t “return” to Catholicism with a nostalgic approval of the status quo. No: virtually everything, to me, is destroyed by, or susceptible to, the apocalyptic fires of deconstruction. Many of the warm theodicies of God–that he is watching over us, so take comfort–have been all but lost on me. I think they are often, per Cormac McCarthy, a version of human vanity and pride. BUT, and this is the clincher for my journey, I ultimately know and am convicted that we must reconstruct. We can’t go on with deconstruction forever. We must find the sparks of life left, the things absolutely worth cultivating and redeeming, and breathe upon them. And, I’ve found Sacred Heart in Camden–as a member of this global Body which has lived through dozens of massive historic social apocalypses–shows me that the Catholic Church has a special capacity for cultivating and rebuilding the goods of humanity after total deconstruction. Maybe even the death of God. In fact, it is among the few institutions which has done it. So, I haven’t read the autobiographies you are talking about. But sometimes I get the idea that many Catholic conversion stories can serve as a sort of Thomas Kinkade painting; it is a soothing reminder of something warm and happy. It serves as a comforting presence. Maybe so. That’s not an entirely terrible reading of Catholicism. But I greatly disliked that I couldn’t beat my publisher in their selection of my subtitle: “rekindling my love for Catholicism.” It fails to summarize my story because “re” means again (and I never had the love), and the phrase seems to imply (if only by sound) that sort of Kinkadian comfort.

Do you think that the Catholic Church has done a better job than the Evangelical Church in staying with and working among the poor within the last century? Does your working relationship with Sacred Heart continue to be positive, and a mutual learning experience? And, how can the Protestant/Evangelical Church move forward in urban ministries with humility?

“A better job” is a very tough thing to answer without a sociological statistical analyst on hand–let alone somebody to define what exactly a good job is. To my knowledge the Catholic Church is the largest distributor of service to the poor in the world. And, this is where it gets a bit more complicated, they have had to spend less time and energy debating their way through what many Protestants had to debate in the 20th century–and that is the problem of the “social gospel” vs the (what do we call it?) “evangelical gospel.” The Catholic balance of teaching has, by my observation, always insisted that this is a false choice. And, as far as I can tell, virtually all Protestants are coming to the same conclusion. Protestants had to go through this partly because Martin Luther told them that the book of James, “an epistle of straw,” should be kicked out of the canon. Meanwhile Catholics wore the disreputable badge of “works,” sticking with James like the stubborn papists they are. So, I would imagine statistically that the Catholics indeed have thrown a, perhaps larger per capita, effort at working among the poor.

My relationship with Sacred Heart indeed continues to be a lasting source of support and inspiration. I am constantly impressed by how much people treat the Church as a family–a dysfunctional one at that. But they treat it with this sense of being bound, almost like marriage, with a sense of tragic finality, a sense of commitment beyond their preference or fancy. Its their home, like it, love it, or hate it. I’m so impressed by that. If nothing else, that is perhaps one of the most powerful weapons we could ever wield against the culture of “consumerism.” And, on this topic of service to the poor, I find that many Catholic parishes have this weighty, constant, and taken-for-granted group of people who go by the name of the St. Vincent DePaul Society. And they are there to weekly, if not sometimes daily, be organizing soup kitchens, food distribution, etc. I love the regularity of it–the sense of “its just what we do”: its as if they would all declare, with a logic as anti-(or post-)-modern as you can get: “its part of my religion to do this.” What a thumb in the eye of that kind of service which somehow really becomes about one’s self, one’s self expression of piety! Instead, what I often see, is people just doing this good work because it must be done or the power of the Spirit within the community simply compells them to. Our problem today is not religion, and its certainly not works. Doug Paggitt, a thinker with whom I differ on not a few points, once put it very well: “the problem with the Pharisess was not that they ‘believed in works.’ It’s that they said they worked but they didn’t.”

Lastly, St. Vincent laid a good ground for humility by saying, “You will find out that Charity is a heavy burden to carry, heavier than the kettle of soup and the full basket. But you will keep your gentleness and your smile. It is not enough to give soup and bread. This the rich can do. You are the servant of the poor, always smiling and good-humored. They are your masters, terribly sensitive and exacting master you will see. And the uglier and the dirtier they will be, the more unjust and insulting, the more love you must give them. It is only for your love alone that the poor will forgive you the bread you give to them.”