Last year, when I agreed to teach a workshop on writing and social change, folks over at Duke asked me to write a short piece on how I make sense of my vocation as a writer. This got me thinking about words—their power and their limits in society and in a life. Whether you’re a writer or not, it turns out words are the tools you end up using, at least some of the time. As Witgenstein said, “Words make worlds.” But can words really change the world–not just the world we imagine, but the world that is? If so, what sort of words? And how might we best shape them to achieve our desired effect? (Do we really understand what change we hope to effect?)

Last year, when I agreed to teach a workshop on writing and social change, folks over at Duke asked me to write a short piece on how I make sense of my vocation as a writer. This got me thinking about words—their power and their limits in society and in a life. Whether you’re a writer or not, it turns out words are the tools you end up using, at least some of the time. As Witgenstein said, “Words make worlds.” But can words really change the world–not just the world we imagine, but the world that is? If so, what sort of words? And how might we best shape them to achieve our desired effect? (Do we really understand what change we hope to effect?)

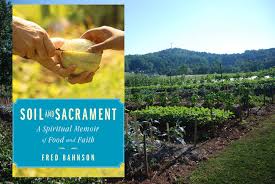

Last week, I had the chance to join my friend Fred Bahnson and a wonderful group of writers at a workshop hosted by the Wake Forest University School of Divinity. It was also a workshop on writing and social change. Fred is the author of an achingly beautiful book, Soil and Sacrament, that hopes, among other things, to help people connect with both heaven above and the soil below. I didn’t get to ask Fred all the questions I had during the workshop, so I asked if we could take up our conversation here. Thanks for joining me, Fred. Here’s where I’d like to start: if you’re writing to change the world, what do you want your words to do to your reader? What was your prayer when you sent your manuscript to Simon & Schuster?

Fred: Thanks, Jonathan, for the invitation to continue this conversation. Well, I do hope my writing changes the world in some way for the better. But in terms of the writing process, I can’t think about that while writing. I find that if I think too hard about my intended audience or what I hope they get from a piece of writing or what societal change might result, then the writing gets overly abstract or argumentative. I have to start with a story or image that I find intriguing, and then write my way into it. When the article or book is finished, I have to trust that it will move people in some way. And the parts that move them are often different than the ones that moved me or that sustained my interest in the writing process.

My hope for the words I give the reader is that they will first find them beautiful and compelling and true. If social change results from a piece of writing, it’s because people found a compelling vision in that work, and they want to see that vision enacted in the world. Our job as writers is to stay true to the vision. We must craft it as faithfully as we can, and not worry overmuch about the result or its lack.

My prayer when I sent my mss. to Simon & Schuster was something like “Lord, thank you that this is over.” Writing that book was a lot of fun, but it was also pretty exhausting.

Jonathan: Fair enough. You know, I’ve been reading William Stafford, a poet we both love, on writing. He says that the longer he taught writing, the more he came to feel that his praise was unhelpful to his students. Praise only taught them what they needed to do to please him as their instructor. But they needed to find their own vision, their own voice, their own reason for writing. I hear you saying something similar. Maybe the first rule of writing to change the world must be to give up our ambition. We write because we’re called to pay attention, to name, to describe. Our responsibility is to do that well and let the consequences fall where they may.

Jonathan: Fair enough. You know, I’ve been reading William Stafford, a poet we both love, on writing. He says that the longer he taught writing, the more he came to feel that his praise was unhelpful to his students. Praise only taught them what they needed to do to please him as their instructor. But they needed to find their own vision, their own voice, their own reason for writing. I hear you saying something similar. Maybe the first rule of writing to change the world must be to give up our ambition. We write because we’re called to pay attention, to name, to describe. Our responsibility is to do that well and let the consequences fall where they may.

But I hear something else in what you’re saying–something you are suggesting is basic to good writing. Namely, that it begins with a concrete engagement with the world. I think most people who write with conviction–people who write for a “cause”–need to hear this. (I am one of them.) You don’t compel people to give themselves to something by telling them how important it is. That’s not how most of us came to care about the issues that matter to us. I care about prison reform because I lived with Roy his first five years out of prison. Because I lived with him, I started visiting prisons. Because I know people whose lives have been crushed by a broken system, I care. If I quote for you the statistics that show how broken this system is, you’ll ask me, “Whose study are you quoting?” But if I tell you about Roy or Al or Frederica or Manuel, you’ll know their story. If I tell it well, you may come to care too.

But don’t you think it’s fair to say that some stories evoke social change more than others? I mean, what’s the difference between a Jane Austen and a Charles Dickens? We do decide, each of us, what we pay attention to, which stories we tell. What effect do these decisions have on the world around us?

Join the conversation by offering your response in the comments below. Check back tomorrow for Fred’s response…