There was only one chair available. It was stuck in a corner, near the guy in uniform.

There was only one chair available. It was stuck in a corner, near the guy in uniform.

Anyone sitting here? I asked.

No, he said.

Mind if I do?

Not at all.

In Columbus, Georgia, soldiers in camo gear are a common sight.

“I hardly ever wear mine out,” the soldier told me later. “Whenever I do somebody wants to thank me or buy me a drink or dinner. It’s nice but I don’t feel deserving of it.”

That’s common too — that those most deserving of attention like it the least.

Knowing these things in advance, I made a choice to give the soldier his personal space. I sat up my computer and began to work, purposely choosing to not engage him in conversation. I didn’t have much time anyway. I was meeting someone for lunch in 30 minutes. I went into the Starbucks for no other reason than to catch up on some correspondence. Hard to get anything done when you’re driving, driving, driving.

I hope my cell phone doesn’t interfere with your connection, he said.

Oh, no, not at all, I replied. But I’m probably going to need a parka in here. I’m not used to this air conditioning.

Feels good to me, he said. It’s been hot here. I’m from Montana and not used to the heat.

That’s how the conversation began. All causal like, about nothing and everything all at once. They call it small talk but in reality, there’s nothing small about small talk. If a person really listens even the gaps between the words can be revealing.

I was listening when he told me that his daddy was a rancher in Montana, or had been until his mama died, a few years ago. What I heard in the words the soldier didn’t say was how much he misses his mama.

“She was a fighter,” he said, all set jaw and misty-eyed.

Fighter is the word we use when we talk about people struggling with a disease, when they die in an unpleasant way. It’s not what we say about somebody dying quickly, the way they do sometimes with a heart attack.

The Ranger insignia on his left-shoulder told me that he’s a fighter, too. I know tough men who have flailed Ranger school, been turned away, even though they were good soldiers.

He had dark hair, dark eyes, charming smile. European good-looks. The sort that could land him a spot on Survivor Island or the cover of GQ.

Married & divorced.

Somebody from back home? I asked.

Yes. No hard feelings though, he said. “I messed it up. I had a drinking problem.”

The result of PTSD, I asked. Or just growing up a farm kid in Montana?

He’d already told me that he’d done three tours in in Iraq. He’d told me about his brothers, too.

One died, he said. The other, well, he shrugged, indicating a lost cause or lost soul. Maybe both.

Killed-in-action? I asked about the brother now dead. I don’t know why I asked that. I just did.

Yes, he said. Afghanistan. Last year.

They’d enlisted together, these brothers. They’d promised their mama they’d never join the military but 9-11 changed all that. His older brother called him and said, I’m enlisting and you are going to drive me to the recruiting center. So he did, and joined up himself in the process. He was already educated, had a fancy degree from University of Portland.

Oh, one of those liberals, I’d said, laughing. He’d laughed,too.

Their mama hit the roof when the brothers told her what they’d done.

Y’all had a big fight, huh? I said.

Yes, he admitted. We did.

He didn’t say it but I could see it beneath those dark lashes, he feels bad about that fight now — now that his mama is dead, now that he’s seen three tours of duty in Iraq, now that his brother is buried beneath a cold marble slab.

I’m proud of him, he said.

I’m sure you are, I said, but I know how empty pride can feel when it’s your brother.. or father.. you’re missing.

He just shook his head in understanding.

William Stafford says every war has two losers, I said.

Yes, he nodded.

Even so, he wants to go to Afghanistan, to fight in the war that cost him his brother.

I understand, I said. But you know how important it is to have someone like you, someone who has been on the battlefield to teach a new generation the ropes of what it means to be a Ranger.

Yes, he agreed. We no longer ask if someone has done a tour — we want to know how many tours they’ve done. If it’s only one, we’re suspicious of them.

I’ll bet.

He told me about the one tour where he earned that Bronze Star. They were clearing an area, looking for insurgents. He jiggled the door knob, right before the bright white flash that knocked him backwards and sent a plume of smoke up from his chest. He thought he was dead but then he saw the fellow with the gun walking towards him.

It seems funny to him now, how he thought he was already dead or dying, what with that smoke rising up and him not being able to breath, but worried at the same time that the guy was going to shoot him in the face and that was going to hurt something fierce. So he reached up to the revolver strapped to his right shoulder and shot the man. Nothing sexy about it, he said. Just firing. Boom. Boom. Boom. The man fell backwards and he rose up.

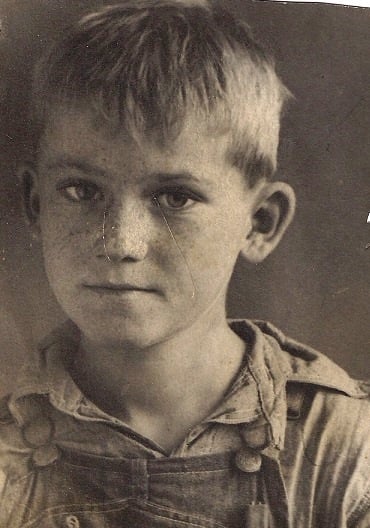

The gear which he didn’t have the year before protected him that day. He rushed into the house and saw a child there, a young boy, pointing a gun at him. A lot of soldiers might have panicked, might have killed the kid. But not him. He kept his cool, acted responsibly despite the threat to his own life. He was able to get the kid to give up his weapons without any more bloodshed. Deeds like that deserve recognition but the best part of all that is not carrying around the PTSD that surely would have been his burden had he killed the young boy.

That’s the thing about enemies that the history books and thriller novels never mention — how much they look just like us, especially when they are afraid.

I told him about Destre, whose father was a Ranger. And about how Destre says that some kids think it’s cool when your daddy dies in war but how Destre knows it’s not — it hurts.

Wow, he said. What an articulate boy.

Very, I said. Smartest boy ever.

Destre understands what those who order others to war fail to — that if we raise up a generation of young kids who think that war is a cool thing then we’ve become exactly like our enemies.

American jihadists.

I gave him a copy of After the Flag and told him if he ever gets back to Oregon, I know this really wonderful girl…

There was a torrential rain driving into Birmingham, but I hadn’t been able to see the road since outside Opelika, while praying for that soldier named Tim, the brother he misses, and their dead mama, who was surely proud of them both.