Marjory Wentworth sits at the dining room table in her Mt. Pleasant, S. C., home, and pushes back the copper  curls falling into her eyes. It is late and she is tried. She has buried a good friend on this day and the grief of it all has exhausted her.

curls falling into her eyes. It is late and she is tried. She has buried a good friend on this day and the grief of it all has exhausted her.

He died too young, this friend of hers, but cancer is indiscriminate. His funeral service reminded Marj of that of her own beloved father, John Heath, who instilled in Marj a love for all things literature.

Unaware that this freckled-faced girl would one day grow up to become Poet Laureate of South Carolina, Heath introduced his daughter to all of his favorite writers.

“My father bought be a copy of Shakespeare soliloquies when I was eleven,” Marj says.

A Marine veteran, Heath used the G.I. Bill to fund his education at Vassar where he majored in English Literature and History. Marjory was raised in a household void of religion but filled with the poetry of Chaucer and Frost. She was twelve when her father fell ill with cancer, and in her freshman year of high school when he died. It broke her heart.

Marjory saw a glimpse of the girl she once was in her friend’s grieving tween-age daughter. “It brought back a lot of sadness,” Marj says. “It’s tough.”

It was during the silence and grief of her own childhood that God became Marjory’s most constant companion. She’d suffered a kidney ailment as a young girl that left her hospitalized and out of school for a good long time. “As a child I spent a lot of time not understanding all the bad things that were happening to me,” she says. “I missed a full year of school in the second-grade. All I could do was read. Without God, I would have been very lonely. I felt as if God was my only friend and that was it.”

Throughout her school years, Marjory prayed that her parents, who held to no particular faith practice, would see fit to send her to a Catholic school. Her parents, however, didn’t know what to make of their daughter’s fixation with Catholics, or God, for that matter. Even now, decades later, Marjory is still drawn to the mystery of the High Church tradition. “Part of it is the poetry, but church has a stillness to it that I like.”

Prayer is poetry, Marjory says. “I don’t know how to separate the two. I feel like when I’m writing I am praying. The two require the same kind of concentration and the same kind of feeling.”

And as is often with prayer, poetry is often a matter of weaving together the tragic with the sacred.

And as is often with prayer, poetry is often a matter of weaving together the tragic with the sacred.

“We poets are not usually a happy go-lucky bunch,” Marjory says, smiling.

Poets look for meaning in the line breaks, the pauses, the in-between places.

Where others see emptiness, poets like Marjory find intention.

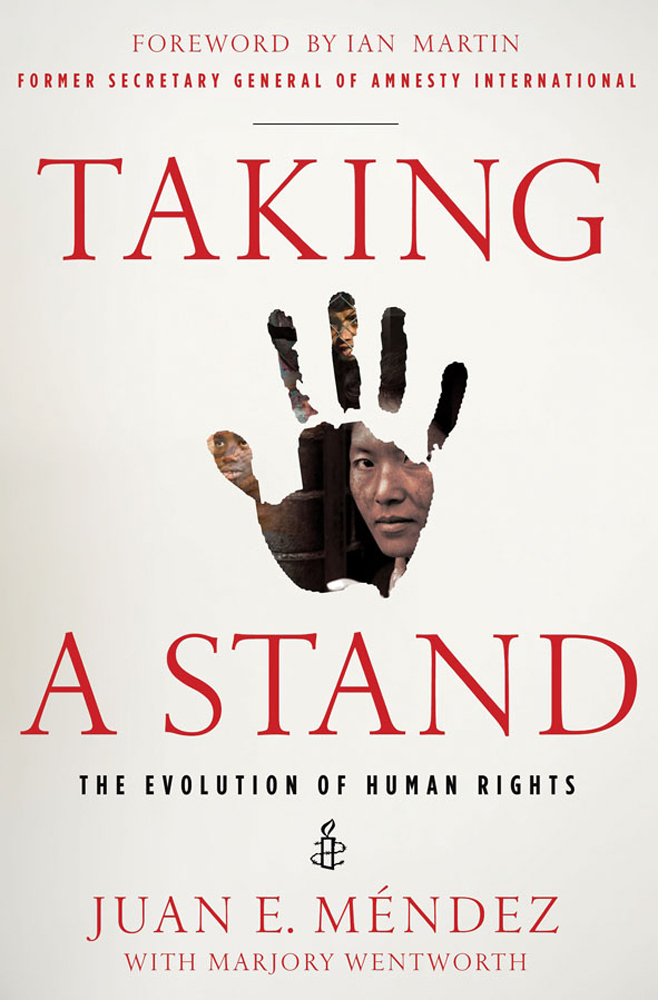

And it was with that in mind, that the poet Marjory Wentworth teamed up with Juan Mendez to write TAKING A STAND: The Evolution of Human Rights. Mendez is the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture.

“Human Rights work is about change,” Mendez says. “The object of our endeavors is change from the situations of oppression, whether individual or collective, to ones of enjoyment of freedom. For such change to occur, we need to imagine a world in which every person, especially the disadvantaged and the vulnerable, is able to fulfill all the capabilities of the human spirit. Imagination, therefore, is what inspires us.”

Can we get an Amen to that?

Pine Pitch

by Marjory Wentworth

Clustered around the edges

of my father’s open grave,

the grown-ups lean into one

another like bunches of crows,

pressing their pale wet faces

against the emptiness

of the slate sky gathering

in the late winter wind.

The flapping minister’s robes

sound like sails unfurling

beside the coffin. It is

as if this man carries

the sea inside of him,

the way my father did.

Pine boughs cover the coffin.

Arranged like flowers from one

end to the other, they fill

the air with Christmas smells.

I think of my uncle, climbing

at dusk through falling snow

to do the one thing he could

still do for this man he loved

like a brother. I consider

the tenderness and courage

it must have taken to tear

the branches one by one,

from the mountainside. And how,

when his arms were full of pine,

he ran stumbling down

the trail he had made alone

through the woods. His hands covered

in dark patches of pitch

that stayed on his skin for days.