For countless readers who have crossed the line from unbelief to embrace the Commandments and the Bible and the Beatitudes and all the lessons which Christ taught, their journey has been guided by the writings of C.S. Lewis.

For countless readers who have crossed the line from unbelief to embrace the Commandments and the Bible and the Beatitudes and all the lessons which Christ taught, their journey has been guided by the writings of C.S. Lewis.

In Mere Christianity, his most popular apologetics work, Lewis leads his readers along the path of sound reason, helping the reader to discern why *A* is true and *B* is not. At the end, the preposterous idea that we were created by a loving God, and that He sent His Son to die a cruel death in our stead, seems the only logical explanation for life.

Despite Lewis’ prominence in Christian apologetics, he was not always a follower of Christ; during his university years, he was an avowed atheist. At Oxford, he often debated philosophy and religion with several Christian friends including J.R.R. Tolkien (best known for the The Lord of the Rings trilogy). And those friends were persuasive! “Really, a young Atheist cannot guard his faith too carefully,” Lewis confided in his conversion story, Surprised by Joy

. “Dangers lie in wait for him on every side.”

Lewis wrote poignantly in Surprised by Joy about his first steps toward faith, toward confirming the existence of God:

“You must picture me alone in that room at Magdalen, night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”

So Lewis embraced Christianity, albeit reluctantly.

* * * * *

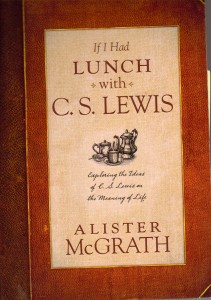

Alister McGrath, in his new new book If I Had Lunch with C. S. Lewis: Exploring the Ideas of C. S. Lewis on the Meaning of Life, cites two major influences on Lewis’s growing interest in Christianity:

First, his friends–such as Owen Barfield–raised questions about his atheism that Lewis knew couldn’t be answered. Second, Lewis read works by Christian writers–such as G.K. Chesterton–which helped him to realize that their faith provided a rich and realistic way of seeing, understanding, and experiencing the world.

Once a convert to the Christian faith, Lewis began his lifelong task of “passing it on”–sharing the gift he’d been given as an “apologist” for the faith. McGrath explains that the three main tasks of apologetics are (1) defending, (2) commending, and (3) translating the faith.

How did he successfully lead so many to faith? For one thing, McGrath reports, C.S. Lewis was both a very good speaker and a very good writer. He was skilled in translating complex ideas into the “cultural vernacular”–that is, he could communicate effectively with an academic audience, but also with the uneducated.

During the Second World War, Lewis was invited to tour Royal Air Force bases and talk to the aircrews about his faith. This experience of speaking to “plodders”–young men who had left school at sixteen and had no intention of doing anything even remotely academic–forced him to translate his ideas into “uneducated language.”

Lewis’s lesson for would-be apologists today is twofold: Listen before we speak; and translate every bit of our Theology into the vernacular, the language of the common man.

But beyond that, McGrath explains, Lewis enriches our vision of apologetics, allowing us to affirm that Christianity makes sense, without limiting it to the “glib and shallow” rationalism that he himself once knew as an atheist. Says McGrath,

“Truth, beauty and goodness all have their part to play in Lewis’s apologetics. Such an “imaginative apologetics” allows us to affirm the reasonableness of faith, while at the same time displaying its power to captivate the imagination.”

There’s so much more in just this single chapter of McGrath’s book. He defends faith utilizing Lewis’ “argument from desire” and his “argument from morality.” He shows how apologetics can be an invitation to step into the Christian way of seeing things, and explore how things look when seen from this vantage point.

Lovers of C.S. Lewis should, of course, read his works. But If I Had Lunch with C. S. Lewis will, I’m sure, become a classic for those who want to better understand the apologist.

* * * * *

If I Had Lunch with C. S. Lewis

If I Had Lunch with C. S. Lewis is a selection of the Patheos Book Club. For more information, to read an excerpt, or to join the conversation, click here.