I Love “Son of Man Study”

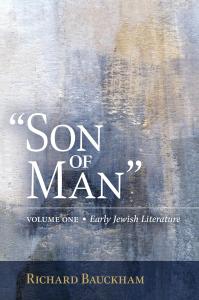

[This “post #1” is the first of a series of seven posts that are a review of Richard Bauckham’s book, “Son of Man”: Volume 1: Early Jewish Literature.]

My favorite biblical study for about the past thirty years has been what scholars call “Son of Man study.” It is because, according to the New Testament (NT) gospels, Jesus used this expression, “the Son of Man,” and applied it to himself way more than any other title or expression, such as “Messiah” or “Son of God.” It appears about eighty times in the sayings of Jesus and it is never said by characters mentioned in these gospels or by the authors of them. (In my book The Gospel—a composite and chronological harmony of these four gospels in the New International Version that includes all details but deletes all repetition—Jesus identified himself as “the Son of Man” thirty-nine times.)

I have several books about Son of Man study in my home theological library. My favorite is Chrys C. Caragounis’s book, The Son of Man: Vision and Interpretation (1986). I think there is nothing in the Bible that provides more insight into the identity of Jesus of Nazareth than the many instances of his self-identification as “the Son of Man” in the four New Testament gospels.

And I think Son of Man study is very important because church tradition has severely misled us Christians about Jesus’ self-consciousness and thus who he was. Nicene and post-Nicene church fathers taught that Jesus being “the Son of God” meant that he was God. Modern scholars, even most Trinitarians, agree that that is wrong according to the Bible. That is, “son of God” language is applied to other men in the Bible, such as the king of Israel (e.g., 2 Samuel 7.14), and even to angels (e.g., Job 1—2). Plus, the expressions, “the Messiah/Christ” and “the Son of God” are often combined in the NT gospels as if being used interchangeably (e.g., Matthew 16.16; 26.63; John 20.31). This indicates that identifying Jesus as “the Son of God” did not mean that he was God.

Moreover, the 5th ecumenical Catholic council of Chalcedon, in the year 451, decided on a construct for Jesus’ identity that it called “the hypostatic union.” It means Jesus had two natures: a human nature and a divine nature. These church fathers reasoned that, in the NT gospels, when Jesus did or said something it was from the exclusive perspective of one of these two natures. Furthermore, they asserted that Jesus being the Son of God referred to his divine nature, and his being the Son of Man referred to his human nature. Nowadays, just about all biblical scholars say both of these dogmatic assertions are wrong. That is, there is nothing in the Bible indicating that Jesus had two natures or that his status as the Son of Man indicated a human nature in contrast to his divine nature. Such false information makes it necessary for Christians to re-learn who their Lord and Savior Jesus Christ really was and is.

Richard Bauckham’s Book, “Son of Man”: Volume 1

Richard Bauckham’s Book, “Son of Man”: Volume 1

Leading New Testament scholar Richard Bauckham has now added his expertise to Son of Man study with his book, “Son of Man:” Volume 1: Early Jewish Literature (Eerdmans, 2023, 447 pp.). It is scheduled to be the first book of a two-volume series. The second volume is to be about Jesus as “the Son of Man” in the New Testament. I am much anticipating it since I regard Bauckham as an excellent scholar. As a Brit, he has distinguished himself as professor emeritus at the University of St. Andrews, a fellow of the British Academy, and a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. I do, however, disagree with Dr. Bauckham’s orthodox position that Jesus is God. (I once heard Dr. Bauckham present a paper at one of the annual meetings of the Society of Biblical Literature, of which I’ve been a member since 1999.) So, during the next few days, I intend to review this most recent and largest book by the professor in a series of blog posts, probably using some of the book’s chapter titles for each of the headlines for these posts.

Dr. Bauckham begins his “Introduction” to this book by stating (p. 1), “The phrase ‘the Son of Man’ occurs about eighty times in the four Gospels in the New Testament but only once in the rest of the New Testament (Acts 7:56). It occurs almost exclusively on the lips of Jesus, and most readers readily recognize that Jesus uses it to refer to himself. But the meaning and significance of the phrase is never explained in the Gospels and is by no means obvious.” Bauckham then recounts that although Jesus’ use of the “Son of Man” expressions has been diligently studied, “a scholarly consensus” of it “remains as elusive as ever.” He adds concerning it, “Even though I argue that the term is never used as a title, I capitalize ‘Son’ and ‘Man’ to signal that it is a technical usage.”

Parables of Enoch & Other Early Jewish Literature

Bauckham has constructed this book in two parts: Son of Man in “The Parables of Enoch” and Son of Man in “The Interpretation of Daniel 7 in Second Temple-Period Judaism.” The Parables of Enoch are extremely apocalyptic and eschatological. Since I specialize in my studies and writings on end times biblical prophecies, The Parables are of particular interest to me even though I do not regard them as divinely inspired like I do the Bible. They are part of an ancient book named 1 Enoch. It is a combination of five “books” that are named, and it is extant only in the classical Ethiopic language known as Ge‘ez. Portions of 1 Enoch exist in other languages. 1 Enoch consists of 108 chapters. Chapters 1-36 are Book 1 named “The Watchers.” Chapters 37-71 are Book 2 named “The Similitudes” or “The Parables.” The first third of Bauckham’s book is about the frequent use of the expression “Son of Man” in The Parables.

Scholars believe that each of the five books of 1 Enoch had different authors and were written at different times. Yet scholars still do not agree on the approximate dates of origin of these books of 1 Enoch. There used to be a bare consensus that all of 1 Enoch was written no later than the first century BCE. But now this is being increasingly contested by 1 Enoch specialists who claim that some of it, including The Parables, was written in the first century CE and thus after the Jesus Movement had begun, which was in about 28 CE. Bauckham is among this group. He says (p. 9), “the Parables was probably written in the late first century or early second century CE.”

There are also other books in ancient Jewish literature designated “Enoch” and numbered, such as 2 Enoch and 3 Enoch. But their content is not of the high quality that 1 Enoch is. I believe as Bauckham does, that The Parables in 1 Enoch are a commentary on the Tanakh, especially on Daniel 7, and that they are well worth reading and studying. I’ve been reading and studying The Parables somewhat since the 1980s.

Bauckham claims that his book is the most detailed study of The Parables ever produced. He says on pp. 19-20 that it is needed due to “the remarkable renaissance of studies on the Parables of Enoch that has taken place in the last fifteen years…. While some of this new interest in the Parables of Enoch is primarily concerned with understanding the place of the work in early Judaism, much of it is also driven by its possible influence on early Christology or even on Jesus himself.” Indeed, I think The Parables help a little in understanding the Son of Man and thus Jesus of Nazareth.

Who Was Enoch?

The name “Enoch” in this ancient Enoch literature is taken from Genesis 5.21-24. It says of an antediluvian, righteous man named Enoch that he was the father Methuselah, the oldest man in the Bible who lived 969 years. It says twice that “Enoch walked with God.” It adds, “then he was no more, because God took him.” This has been interpreted commonly to mean that Enoch did not die, and God took him alive to heaven. Regardless, many readers of The Parables have had an objection to them, as I have, because the author reveals at their end that the archangel Michael “carried me off [in] my spirit, and I, Enoch, was in the heaven of heavens” (1 Enoch 71:5).

So, the author of The Parables, who lived in the first century BCE or CE, seems to claim he was literally that antediluvian Enoch of thousands of years ago. Yet Bauckham explains (p. 26), “The author of the Parables was a learned scriptural exegete. We should not be misled by the fact that he represents the content of his work as heavenly disclosures made to Enoch. That belongs to apocalyptic genre. The author did not see the visions he ascribes to Enoch; rather, they are a vehicle for what he has learned from his study of the scriptures.” Seems strange to me! But then, apocalyptic literature can be pretty strange and sometimes not too pretty!

The Parables Are Mostly about Daniel 7.13-14

The first part of Bauckham’s book is about The Parables because of frequent reference therein to “the Son of Man.” Most scholars who specialize in studying 1 Enoch agree that the author of the Parables uses this Son of Man expression (I will also call it a “title” even though Bauckham objects to this) in sole reference to Daniel 7.13-14, which I regard as perhaps second in importance in the Old Testament to the Shema in Deuteronomy 6.4-5. Daniel 7.13-14 is a vision Daniel had as in the NIV:

“In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a son of man, coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power, all peoples, nations and men of every language worshiped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom is one that will never be destroyed.”

(Throughout my review of Bauckham’s book, I will quote the Bible by using the NRSV unless otherwise noted, as here. I don’t use it here since it has “one like a human being” in Daniel 7.13, to which I object. I believe this expression refers to Jesus, who was a human being and therefore not “like a human being.” [See Deuteronomy 18.15; Hebrews 2.17.] “One like a Son of Man” allows for Jesus to be like other men who were born into this world by means of natural procreation, therefore having a physical father; yet I believe it the word like provides that he was conceived by the Holy Spirit in the womb of Mary and thus indicates his virgin birth, as in Matthew 1.20-21 and Luke 1.31-32.)

Daniel 7.13-14 originally was written in the Aramaic language. The book of Daniel has a strange linguistic feature other than its highly apocalyptic nature. The most ancient manuscripts of it have Daniel 1-2.4b and Daniel 8-12 written in the Hebrew language, whereas Daniel 2.4b—7 is written in Aramaic, a sister language of Hebrew. Thus, the critical Aramaic expression in Daniel 7.13 is kebar enash, which means “one like a son of man since the prefix ke means “like,” bar means “son,” and enash means “man.” This is the only place in the Tanakh (Old Testament) where this expression occurs. The expression bar adam occurs in the Hebrew Old Testament numerous times. It can mean the personal pronoun “I” when the author uses it of himself, or “you, man,” when God uses it of his prophet, such as about 90 times in Ezekiel, but not with a word meaning “like” as ke does in Dan 7.13.

Although Daniel has the expression “one like a Son of Man,” The Parables has the expression “the Son of Man” as an obvious, shortened form of “one like a Son of Man” in Daniel 7.13. In the four NT gospels, Jesus always used this shortened form. It appears to be a capitulation to this Enochian use, other ancient Jewish literature, or even just oral tradition, all due to convenience.

The Transmission History of 1 Enoch

Bauckham begins his book in his chapter entitled “Introduction to the Parables of Enoch” by saying of 1 Enoch (p. 7), “It is a compilation of several ancient works ascribed to or associated with the biblical figure Enoch. It is usually divided into five major works” that “were originally all distinct, composed at various times in the Second Temple period, but none has survived entirely in the original language. All were composed in a Semitic language (Aramaic in most cases, possibly Hebrew in the case of the Parables), translated into Greek and then translated from Greek into Ethiopic. The Ethiopic version remains the only complete version of any of them.”

Due this convoluted history of extant manuscripts of 1 Enoch or portions thereof and for other reasons, such as that the Ethiopic version of the Parables “contains substantial interpolations,” Bauckham admits, “This obviously makes study of the Parables as a work of Second Temple-period Judaism a hazardous, perhaps even questionable enterprise” (p. 11). However, many fragments of 1 Enoch were found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are important to study for help in understanding the Old Testament. Furthermore, prior to the Catholic Church deciding officially what books were divinely inspired and thus to be included in the New Testament, some communities of early Christians regarded 1 Enoch as divinely inspired. The ancient Church of Ethiopia includes 1 Enoch in its Bible, thus regarding it equally divinely inspired.

The Construction of The Parables

Bauckham explains (p. 15), “The Parables of Enoch is composed of three ‘parables.’” While messale in Ethiopic means “parable,” Bauckham explains, “The author of the Parables probably uses it to mean something like ‘eschatological oracle’ or ‘prophecy of the final judgment…. The theme of eschatological judgment dominates the Enoch literature” (p. 16).

Bauckham then concludes this introductory chapter by stating (p. 16), “The new focus on eschatological prophecy drawing on Daniel and the biblical prophets enables the author of the Parables to introduce a major new element into the eschatological expectation: the introduction of a Messianic Figure (variously called ‘that Son of Man, ‘the Chosen One,’ and ‘the Anointed One’) as God’s agent in executing the final judgment. This may indeed have been the author’s overriding aim. It is the aspect of the Parables with which the following chapters will be concerned.”

More Observations that Involve Some Perplexity

It is interesting to me that Bauckham is a Trinitarian who therefore believes that Jesus was both fully man and fully God, yet he says often and most emphatically throughout this book that the author of The Parables believed that “the Son of Man” would be an actual human being to appear sometime in the future and that he will not be divine, thus a God-man. Yet many Trinitarian scholars have tried to cite Daniel 7.13-14 to prove that it refers to Jesus as divine. They present several different reasons, which are unconvincing to me, such as that only God rides on clouds.

Another intriguing thing for me about Bauckham’s book is that he explains how the author of The Parables believed so strongly that “the Son of Man” would conduct the judgment of God in the eschaton, i.e., the beginning of what Jesus called “the world to come.” This is clearly what the New Testament says repeatedly. Yet there has seemed to me to be no justification for making this assertion based on Daniel 7. Yet we read that when the high priest Caiphas said to Jesus as the Sanhedrin’s examination and thus interrogation of him, “‘Tell us if you are the Messiah, the Son of God.’ Jesus said to him, ‘You have said so. But I tell you, from now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven’” (Matthew 26.63-64). The high priest then called for the charge of blasphemy that required the death penalty (vv. 65-66).

All scholars agree that in his answer to the high priest, Jesus alluded to Psalm 110.1 and Daniel 7.13. And many recent scholars believe this was a cryptic way of saying that, although Caiaphas and those Sanhedrin members were his judges, he would be their judge at the end times bema. That will be a far more important judgment because it will determine eternal destinies. Since the author of The Parables believed strongly that the Son of Man in Daniel 7.13 will possess God-given authority to judge, if he penned The Parables during the first century BCE as most scholars believe, to me this is a very intriguing insight. And as I proceed with subsequent posts in reviewing this Bauckham book, I will explore this idea more.

Bauckham even admits this study caused him to see some things he had been wrong about previously. For, he says in his preface (p. ix)., “I was coming up with new observations and conclusions, but also that these were unexpected and surprising to me.” I’ll get into that also.

[In Kermit Zarley’s magnum opus, The Restitution: Biblical Proof Jesus Is NOT God (570 pp.), he has twenty pages on Daniel’s “Son of Man.” See also his 100-page primer for this book, The Gospel Corrupted: When Jesus Was Made God]

[Click here to go to post #2 of this multiple-post review of Richard Bauckham’s book, “The Son of Man”: Volume 1: Early Jewish Literature.]

Here are links to the other posts of this review of Bauckham’s book:

Post #2: “The Messianic Figure in The Parables of Enoch”

Post #3: “Worship of the Son of Man in the Parables of Enoch”

Post #4: “Introduction to Jewish Interpretations of Daniel 7”

Post #5: “Dead Sea Scrolls Have Oldest Interpretation of Daniel 7.13”

Post #6: “Josephus Was an Accomplished Historian and Biblical Exegete”

Post #7: “Conclusions of Ancient Jewish Interpretations of Daniel 7.13”