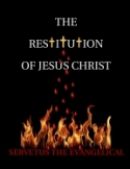

As author of The Restitution of Jesus Christ (2008), I used the pseudonym Servetus the Evangelical. I created it based on Michael Servetus. (This book is available at kermitzarley.com.) The following is an excerpt about him from my book:

As author of The Restitution of Jesus Christ (2008), I used the pseudonym Servetus the Evangelical. I created it based on Michael Servetus. (This book is available at kermitzarley.com.) The following is an excerpt about him from my book:

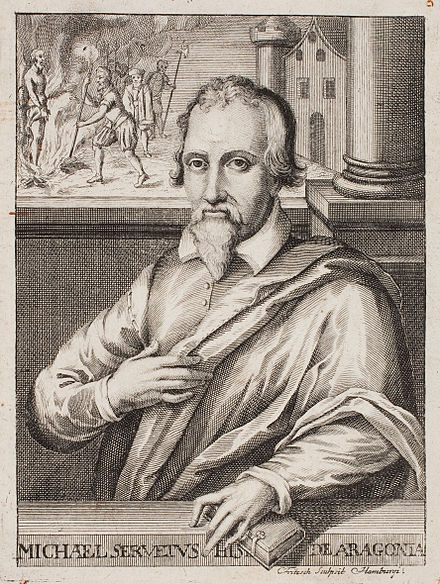

Michael Servetus

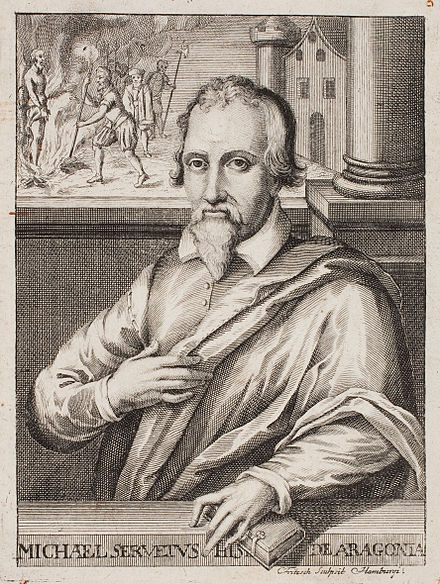

That man was Michael Servetus (Sp. Miguel Serveto Conesa, 1511-1553).[1] Born in Villeneu[f]ve, Spain, to a devoted Catholic family of nobility, his father was a notary and his mother was a Jew. A child prodigy, he grew up in the early stages of the Spanish Inquisition, when the government forced adherence to Catholic Christianity and thus its doctrine of the Trinity. This religious persecution by the RCC aroused serious questions in Servetus’ youthful mind. While studying law at the French University of Toulouse at the age of seventeen, he became shocked at his first reading of the Bible, which he did in its original languages. He concluded that the Bible did not support the doctrine of the Trinity. He also asserted that Christians should not demand adherence to doctrines that are unessential to their faith, as was this doctrine, especially if unsupported by the Bible.

Consequently, at the youthful age of twenty, Servetus naively set himself to the daunting task of correcting this supposed theological error. As an assistant to Quintana, confessor of Emperor Charles V, Servetus became familiar with some of the inner workings of the RCC, and he was dismayed by it. Spurned of a requested hearing with his church and then denied interviews with Protestant leaders (except Oecolampadius), especially in France and Switzerland, he quickly wrote and published his first theological book. Entitled On the Errors of the Trinity (1531), it consisted of only 119 pages.[2] Early Protestant leader Wolfgang Capito wrote that “the book became remarkably popular.”[3] Even at that early age, Servetus was fluent in Spanish, Latin, Hebrew, and Greek, the last two being the original languages of the Bible. Servetus’ father apparently had trained him in these languages during his youth, and he later learned Arabic as well.

Consequently, at the youthful age of twenty, Servetus naively set himself to the daunting task of correcting this supposed theological error. As an assistant to Quintana, confessor of Emperor Charles V, Servetus became familiar with some of the inner workings of the RCC, and he was dismayed by it. Spurned of a requested hearing with his church and then denied interviews with Protestant leaders (except Oecolampadius), especially in France and Switzerland, he quickly wrote and published his first theological book. Entitled On the Errors of the Trinity (1531), it consisted of only 119 pages.[2] Early Protestant leader Wolfgang Capito wrote that “the book became remarkably popular.”[3] Even at that early age, Servetus was fluent in Spanish, Latin, Hebrew, and Greek, the last two being the original languages of the Bible. Servetus’ father apparently had trained him in these languages during his youth, and he later learned Arabic as well.

In his book, Servetus affirms the sole authority of the Bible in doctrinal matters and denies that it contains either the doctrine of the Trinity or its terminology. He lodges a scathing rebuke against the Church, asserting that its inclusion of the doctrine of the Trinity in Church creeds reveals that they are mere inventions of men. He contends that the Bible designates the Holy Spirit only as God’s “activity,” i.e., the power of God, and thus not a person. He alleges that the Trinity doctrine, as proclaimed in the Athanasian Creed, is an insuperable and unnecessary obstacle in the conversion of Jews and Muslims to Christianity. And he rightly insists that he believes in the Trinity as generally taught by the apologists. Finally, Servetus contends that the Protestant Reformation had not gone far enough and that he is attempting to reestablish pre-Nicene, biblical Christianity.

As for Servetus’ Christology, he denies the eternal generation of the Son. This free-thinking Spaniard affirms the virgin birth and claims that Jesus’ Sonship began at His incarnation, in accordance with Lk 1.32-35. So, Servetus denies that Jesus preexisted. He argues that Scripture only verifies that the Logos preexisted as a manifestation of God the Father, not as a separate Person from Him, and it united with Jesus at His conception. Servetus even admits that Jesus is God by agreeing with the apologists in explaining that His divinity is derived solely from the Father. Yet Servetus affirms the following major elements of Church orthodoxy: Jesus was the Christ who performed miracles, died for our sins, arose alive from the tomb, appeared to His disciples, and ascended into heaven where He was exalted by sitting at God’s right hand, and now awaits His second coming.

As with the writings of the ante-Nicene fathers, whom Servetus cites liberally for support, On the Errors of the Trinity suffers from much Logos speculation and not a little incongruity. But it reveals that Servetus had a considerable knowledge of the Bible as well as patristic and Scholastic literature. Andrew M.T. Dibb gives an unbiased critique of Servetus’ book, saying, “The Trinitatus is not an easy book to master. Although liberally annotated with Biblical and Patristic references, Servetus makes it difficult for a reader to follow his argument. It seems to have little cohesion and the outline of his argument is difficult to follow. However, although it is often obscure, there is a progression of ideas in the Trinitatus that can be roughly illustrated under the paradigm that Christ is a man, Christ is the Son of God, Christ is God,”[4] but not fully God as determined at Nicaea.

One year after Servetus published this first of his theological works, he published a booklet entitled Dialogues on the Trinity to further clarify his previous views. In it, he even describes his previous book as a “barbarous, confused and incorrect book” that is “incomplete and written as though by a child for children.”[5] That same year Servetus published another book entitled On the Justice of Christ’s Reign.

The danger of being anti-Trinitarian in the early Protestant Reformation cannot be over-exaggerated. Both the Roman and Protestant churches agreed on the doctrine of the Trinity, treating it as foundational to Christianity. As Servetus’ book about the Trinity circulated in Europe, governmental authorities usually banned it and confiscated copies to burn them. Servetus, fearing for his safety, abandoned his passion for theology, returned to France, and disguised his identity, changing his name to Michel de Villeneuve. In this the doctor provided a clue to his identity, since his birthplace was Villaneuva de Sijena.

While in France, this brilliant and multi-talented Spaniard attained several notable achievements as a consummate multi-professional. He became an editor and a translator of classics, temporarily a university mathematics professor, then an inventor, and briefly a pioneer in geography. But most of all, Servetus attended medical school in Paris and became a distinguished physician. His twelve-year medical practice in Vienna included his being the personal physician for the archbishop. His keen intellect was manifested when he discovered and wrote about the pulmonary circulation of the blood more than a century before the medical community discovered it. Servetus also translated and edited the famous Santes Pagnini Bible. He added a preface to it, in which he recommends the study of the history of the Hebrew people in order to achieve a better understanding of the Bible. Servetus was an indefatigable researcher. He read much Judaica, the writings of Greek philosophers, and church fathers. Because of his many skills and a critical mind, modern scholars recognize Michael Servetus as a forerunner of biblical criticism. Some historians even regard him as “the father of the freedom of conscience.”

Because of Servetus’ knowledge of Hebrew, he correctly argued that the common Hebrew word for “God,” the plural elohim, does not provide for a trinity of Persons in a supposed Godhead. For this and other reasons, Jewish scholar Louis Israel Newman concludes, “it is apparent that Servetus was equipped for Biblical exegesis far better than his contemporaries.”[6] Indeed, in many ways Servetus was a man ahead of his time.

But this alias Dr. Michel de Villeneuve could no longer restrain his penchant for expounding with the pen God’s truth, as he perceived it. After twenty years of public silence on theology, and despite a successful medical practice and peaceful life at Vienna, he was discontented. So he resumed his theological career by writing and publishing another provocative book, in 1552, this one under his real name. It was his magnum opus, being 734 pages in length, and it contained his treatise on the circulation of the blood. Entitled Christianismi restitutio (ET The Restitution of Christianity), he meant its restoration. Catholics and Protestants alike detested it just as vehemently as they did his first book. To make matters much worse, back in 1546 Servetus had started a lengthy correspondence with the astute John Calvin that lasted for over a year, with Servetus writing thirty letters to Calvin. (The two simultaneously had been students in Paris.) The tenor of these letters soon deteriorated dramatically, with Servetus hurling a cascade of invectives at Calvin. Indeed, the excitable Spaniard could be very obstinate and caustic in controversy. But then, Calvin was a well-known master of rhetoric himself.

John Calvin had been made master of Geneva, Switzerland. The city offered him the post, and his friend, Guillaume Farel, a fanatical Reformer, had threatened Calvin with God’s judgment if he refused to accept it. Geneva afterwards became the capital of the Reformed churches and a sort of model theocracy. Calvin instituted much restrictive legislation there. Citizens were reprimanded and even punished for not greeting him with the title “Master.” Many of them declared him a tyrant. Although John Calvin was small in stature, even frail and often rather sickly, he admitted to having a violent temper and absolutely no tolerance whatsoever for criticism of himself.

Marian Hillar is a contemporary authority on Servetus as well as Calvin’s role in the execution of Servetus. Hillar alleges:

“Calvin in fact established a dictatorship, becoming a civil and religious dictator. Geneva was nicknamed Protestant Rome and Calvin himself—the Pope of the Reformation…. Calvin introduced an absolute control of the private life of every citizen. In his doctrine every man was a wretched being not worthy of existence, a sinner and evil doer, ‘trash’ (une ordure). He instituted a ‘spiritual police’ to supervise constantly all Genevese and they were subjected to periodical inspections in their households by the ‘police des moeurs.’ Anything that smacked of pleasure—music, song, laughter, theater, amusement, dancing, playing cards, even skating—was declared ‘paillardise’ and severely punished. Calvin managed to destroy the normal bonds between people and simple decency inducing them to spy upon each other. His method of intimidation and terror was so refined that it involved control of every petty activity.”[1]

The Arrest, Trial, and Execution of Servetus

Because of Servetus’ last book, Calvin summoned the Catholic Inquisitors to arrest him in Vienne, France. They promptly did so on April 4, 1553. But the doctor outwitted his captors and escaped. Later, he headed for northern Italy where he planned to practice medicine among new groups of anti-Trinitarians, many of them Anabaptists.

Unfortunately for Servetus, it seems that he could not avoid traveling through Geneva. And mostly on account of Master Jean Calvin, Geneva had strict Sabbatical laws. One of them was the mandatory requirement of church attendance on Sunday.

Servetus apparently feared arrest if discovered breaking the “Christian Sabbath.” So he took a calculated, but foolish, risk. On August 13th, 1553, he attended the large church where Calvin pastored and preached every Sunday. A parishioner uncannily recognized the doctor and quickly informed the Master. Calvin hailed the heresy-hunting Inquisitors to arrest Servetus again, this time charging him as an escaped prisoner.

During the next seventy-five days, Calvin led Geneva’s other thirteen Protestant pastors—called “the Venerable Company of Pastors” and members of the Little Council of Geneva—in an intense doctrinal interrogation of Servetus and his two main books. Due to Calvin’s frail health and civil governing duties, it was orchestrated by him but conducted by his student secretary living at Calvin’s home—Nicholas de la Fontaine. These judges were incensed at Servetus’ denial of the doctrine of the Trinity and thus Jesus’ eternal-divine Sonship. Servetus had asserted in his first book that the post-Nicene Trinity was “a Cerberus” (a pagan, three-headed, monster god.) But these pastors were further repulsed at Servetus’ denial of infant baptism and the immortality of the soul. Calvin was especially irritated with Servetus labeling his opponents as “Trinitarians.”

The civil court directed Calvin to write a draft of the interrogation, with Servetus’ annotations appended. It consisted of thirty-eight extracts from Servetus’ two books. Calvin pronounced these extracts “partly impious blasphemies, partly profane and insane errors, and all wholly foreign to the Word of God and the orthodox faith.” This document was submitted to four major cities in Switzerland for the judgment of their city councils and church pastors. They ruled Servetus guilty and seemed to approve of his execution.

Switzerland was like most European states in that it was a church-state. Geneva’s court condemned Servetus in accordance with the Codex of Justinian. Established by the Roman Empire during the 6th century, it prescribed the death penalty for those denying the church doctrine of the Trinity or infant baptism, thus advocating rebaptism as adults. Servetus had committed both infractions. These were the only two legal charges brought against him. The Geneva Reformers, however, had earlier abolished all (Catholic) canon laws, so that this was not the legal basis for their condemnation of Servetus.

Purposeful judicial irregularities were made in the trial of Michael Servetus.[2] Although he was entitled by law to counsel, which he requested, it was refused on the illegitimate grounds that he was intelligent enough to defend himself. When Calvin and the others completed their lengthy interrogation of Servetus, they pronounced him guilty of grave heresy and blasphemy against “the Lord God Jehovah” for publishing his two main books and that such infractions were deserving of death. The court had authority to try defendants accused of crimes committed within Geneva’s jurisdiction, yet this was never mentioned in the trial. Nor was an attempt made to prove that Servetus committed such crimes in Geneva or that any of his books had ever been sold there, much less been there. And the court never stated the legal basis for its condemnation of Servetus. It only was inferred in its judgment that the accused was guilty of breaking the Mosaic law of blasphemy as stated in Lev 24.16 and perhaps Deut 13.

Ironically, seven years earlier Calvin had vowed in a letter to his friend Farel about Servetus, that “if he come here [to Geneva] … I will never permit him to depart alive.” Calvin only stated his opposition to burning Servetus at the stake; but the other pastors surprisingly overruled him. As a consolation, they offered Servetus hanging rather than tortuous burning on the condition that he confess to them the words, “Jesus Christ, the eternal Son of God.” The accused remained steadfast in his convictions and refused.

Servetus was presented with his condemnation and death sentence only a few hours before his execution. He apparently did not expect it, since he was shocked when so informed. He quickly requested a meeting with Calvin, pleading for his forgiveness. But the Reformer stayed true to his convictions as well, refusing to grant a pardon.

Servetus was executed on the Plateau of Champel just outside Geneva during midday on October 27, 1553. M. Hillar relates the scene as follows: “No cruelty was spared on Servetus as his stake was made of bundles of the fresh wood of live oak still green, mixed with the branches still bearing leaves. On his head a straw crown was placed sprayed with sulfur. He was seated on a log, with his body chained to a post with an iron chain, his neck was bound with four or five turns of a thick rope. This way Servetus was being fried at a slow fire for about a half hour before he died. To his side were attached copies of his [last] book” by a chain.[3] With a large crowd witnessing the proceeding, and in a moment of hushed solemnity, the executioner reached forth with his fiery torch and ignited the mass of kindling surrounding its victim. Flames quickly arose and engulfed his emaciated body. For a while, the accused heretic uttered painful shrieks and groans. Just before he expired, and recalling the consolation that had been offered to him only hours prior, he cried out with a loud, penetrating voice, “Oh Jesus Christ, Son of the eternal God, have mercy upon me.” Even in his last dying breath, Michael Servetus passionately held to his convictions, proclaiming what he had perceived to be original, biblical Christology. Church historian and strong Trinitarian P. Schaff admits concerning Servetus, “it is evident that he worshipped Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior.”[4]

So, Protestant leaders afflicted Michael Servetus with martyrdom in his forty-second year. Yet this alias Dr. Michel de Villeneuve—physician, physiologist, humanist, and scholar—was a devout follower of Jesus Christ. Throughout that final day of his life, Servetus portrayed a most exemplary spirit. This proud and illustrious Spaniard refrained from his usual vitriolic attacks on his accusers. Instead, chained to the stake, he humbly and graciously prayed out loud, asking God to pardon all his accusers, even John Calvin.

What a contrast was the indomitable Jean Calvin, Master of Geneva! The famous Reformer afterwards never recanted of his participation in this dastardly deed. Despite an angry uproar against Servetus’ execution, which news spread like wildfire in much of Europe, the arguably dictatorial Calvin remained stubbornly impenitent the rest of his life about this Servetus affair. The next year he published a book defending his action, saying, “Whoever shall maintain that wrong is done to heretics and blasphemers in punishing them makes himself an accomplice in their crime and guilty as they are. There is no question here of man’s authority; it is God who speaks,… Wherefore does he demand of us … to combat for His glory.”[5] Calvin implores the two Mosaic laws against blasphemy even though they apply to those guilty of idolatry or blasphemy against Yahweh.[6]

On the contrary, Servetus was a devout worshipper of Yahweh as the one and only true God. And he exalted Jesus as the Christ, God’s special Son, and the only Savior from sin for all humankind. Thus, this application of the two Mosaic laws of blasphemy against Servetus is absolutely baseless. Actually, Servetus’ faith corresponded much more closely to the Jewish concept of Yahweh as the one God than did the traditional, Trinitarian view of God held by Calvin and all other leading Reformers and Catholics.

[1] M. Hillar, Michael Servetus, 153-54.

[2] M. Hillar (Michael Servetus, 187-88) lists the following legal irregularities: (1) Servetus was refused counsel without reason, despite requesting it twice and being guaranteed such by law; (2) he was tried for his book on the Trinity despite it being published twenty-three years prior and in another state; (3) he never published or dogmatized in Geneva; (4) the accusation that The Restitution of Christianity corrupted Christians was baseless since it had just been published and not one copy had been sold.

[3] M. Hillar, Michael Servetus, 185. Historians are divided on which book it was and if one or two.

[4] P. Schaff, History of the Christian Church, 8:789,

[5] John Marshall, John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture (Cambridge: University, 2006), 325.

[6] Calvin also argued against interpreting Jesus’ parable of the wheat and the tares as implying religious toleration of heretics (Mt 13.29 par.), and he did the same concerning Gamaliel’s wise counsel (Ac 5.34).

[1] I have allotted an inordinate amount of space to Servetus, not only because I have drawn my pseudonym from him. He knew six languages and practiced six intellectual professions. P. Schaff (History of the Christian Church, 8:786) says Servetus “was one of the most remarkable men in the history of heresy.”

[2] The full title (but in Latin) is On the Errors of the Trinity. In seven books, by Michael Servetus, Spaniard from Aragonia, also known as Reves.

[3] Indebted to Marian Hillar with Claire S. Allen, Michael Servetus: Intellectual Giant, Humanist, and Martyr (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2002), 26.

[4] Andrew M.T. Dibbs, Servetus, Swendenborg and the Nature of God (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005), 67.

[5] Dialogues on the Trinity, Greeting.

[6] Louis Israel Newman, Jewish Influences on Christian Reform Movements (New York: Columbia University, 1925), 534.

………………

To see a list of titles of 130+ posts (2-3 pages) that are about Jesus not being God in the Bible, with a few about God not being a Trinity, at Kermit Zarley Blog click “Chistology” in the header bar. Most are condensations of my book, The Restitution of Jesus Christ. See my website servetustheevangelical.com, which is all about this book, with reviews, etc. Learn about my books and purchase them at kermitzarley.com.

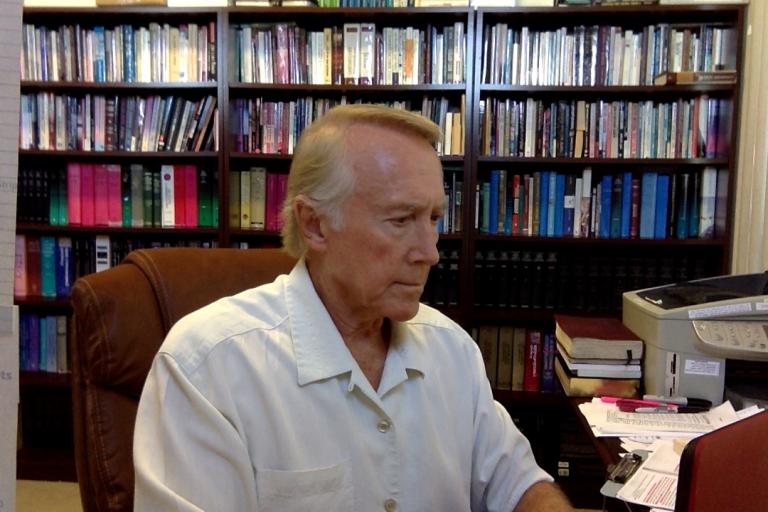

But I did not develop in Christian understanding until I went to college at the University of Houston, in Houston, Texas. I soon got involved with Campus Crusade for Christ and began attending an independent Bible church named Berachah Church. (It was located right next to the successful, original, shopping mall The Galleria.) Bob Thieme was the pastor. In about 1950, he had graduated from Dallas Theological Seminary (DTS) with honors. This school is the bastion of Dispensational Theology throughout the world. And Thieme had specialized in Greek since college. Berachah was my church home from late 1959 through 1970.

But I did not develop in Christian understanding until I went to college at the University of Houston, in Houston, Texas. I soon got involved with Campus Crusade for Christ and began attending an independent Bible church named Berachah Church. (It was located right next to the successful, original, shopping mall The Galleria.) Bob Thieme was the pastor. In about 1950, he had graduated from Dallas Theological Seminary (DTS) with honors. This school is the bastion of Dispensational Theology throughout the world. And Thieme had specialized in Greek since college. Berachah was my church home from late 1959 through 1970. Yet, I eventually came to the opinion that God had used Bob Thieme in my life to make me a more critical thinker about everything, especially my theological beliefs. Rather than this making me a weaker Christian, as Thieme warned me one time privately, calling me “a reversionistic believer,” it has done just the opposite and made me stronger in the faith.

Yet, I eventually came to the opinion that God had used Bob Thieme in my life to make me a more critical thinker about everything, especially my theological beliefs. Rather than this making me a weaker Christian, as Thieme warned me one time privately, calling me “a reversionistic believer,” it has done just the opposite and made me stronger in the faith.