Jesus’ path gets increasingly dangerous as we move through Mark’s Gospel. At the same time he seems to be more and more isolated from his own disciples. Here we’ll see how Mark gives his readers a little hope. He provides some symbolic clues about a more hopeful direction for Jesus’ story.

Thirteenth in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and, looking ahead, a Table of Contents are HERE.

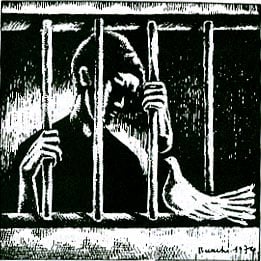

You have to sympathize with Mark’s first readers. Hope is a precious commodity. They live in an unsafe time for Christians. Their new ideas and ways spark opposition from many sides—Romans, establishment Jews, even the rebels. Mark’s community could use an uplifting story of heroes triumphing against the odds, like Judith or Esther of old, or even like the seven brothers of 2 Maccabees, defiant to the end and confident of eventual victory. I always figured the story of the Transfiguration was that kind of story.

But Mark’s story, which has now reached the halfway point, is nothing like an assurance of triumph. Ched Myers locates the Transfiguration solidly within the kind of story Mark has been telling. We see Jesus winning skirmishes with scribes and Pharisees, but we sense also growing danger. Jesus’ followers should be of one mind with Jesus, should be among the heroes of the story. Repeatedly they fail to understand. And there’s an uncomfortable suspicion that Mark’s audience, which includes us, shares that misunderstanding.

From where we stand, we “know” the story ends with the triumph of Jesus’ resurrection. Myers questions whether we are hearing the story the way Mark wants to tell it. Christian triumphalism seems far from what Mark offers his audience.

Our hope fulfilled, or the Cross?

We’re heading toward the Transfiguration, but are we ready for it? Are the disciples, and Peter especially? In a triumphant spirit Peter confesses Jesus as the Messiah, but that triumphalism has to be quashed. At the Transfiguration Jesus’ identity comes brilliantly into focus, but is that one of victorious Messiah or the cross? The disciples lean toward the former, Jesus insists on the latter.

Two miracles surround the section that includes Peter’s “confession” and the Transfiguration. They are a healing and an exorcism. In different ways they help to soften the impact of Mark’s narrative of misunderstanding. These miracles serve as introduction and conclusion to a chapter in Mark’s story, Myers says. In this post I will look at the two bookends, the two signs of hope. I’ll save the events from Peter’s confession to the Transfiguration for the next post.

The healing of the blind man of Bethsaida.

The first of these bookends seems like just another one of those odd events of which history is full. I never read it expecting any special meaning. But with Mark that’s not a safe bet. Jesus cures a blind man from Bethsaida. (8:22-26)

The odd thing is it doesn’t go right at first:

Putting spittle on is eyes he laid his hands on him and asked, “Do you see anything?

Jesus doesn’t seem very confident at this point.

The man does see but not very well. People look like trees walking about. It takes a second zap from Jesus for the man to see clearly.

No explanation is given. It apparently wasn’t any lack of faith in the man and not likely any weakening of Jesus’ powers. But Mark often uses sight as a metaphor for understanding, and this complicated incident becomes a complicated metaphor. It signals both the disciples’ poor grasp of what Jesus is about and the hope that in the end they will understand more completely. It also signals that the overcoming of the disciples’ blindness won’t be easy.

The exorcism of the boy with a demon

Now we’ll skip to the second bookend and see how Mark again gives his reader a signal that there is hope for Jesus’ followers. (Mark 9:14-27) He does, after all want us to keep reading.

We’re coming down from the mountain of the Transfiguration; that is, Jesus is, with Peter, James, and John. There is a commotion. Jesus’ other disciples have been trying and failing to cast out a devil. Some scribes are making much of that fact. Jesus bemoans a “faithless generation” for a while and then asks for the possessed boy. The boy’s father enters a desperate plea for help: “if you can do anything.” “IFF!” says Jesus, and then follow two famous lines:

Everything is possible to one who has faith.

and

I do believe, help my unbelief.

The father doesn’t understand any better than the disciples, but at least he knows it, and he knows where to go for help. Jesus is able to cast out the devil where the disciples failed, and Mark’s readers get another little dose of hope. At least somebody may be open to what Jesus is about.

A more difficult devil?

This episode concludes with another challenge to understanding, at least for me.

The disciples ask Jesus why they couldn’t drive the demon out. He answers, “This kind can only come out through prayer.” (Mark 9:28-29)

It seems odd to me. The apostles had already cast out several demons. Why was this one different? Jesus mentions prayer, and that seems reasonable. But we didn’t notice that Jesus was praying as he cast out the devil. In fact, the idea of praying has been absent up to this time in Mark’s Gospel. Prayer seems to come out of the blue.

A guess about the Transfiguration and prayer

Or does it? Mark doesn’t say that Jesus was praying in the desert, where the devil tempted him. We can assume that he was, and that’s one connection between prayer and the demonic. I’d like to make another assumption about Jesus praying and risk a guess about history and the Transfiguration.

The Transfiguration story could be an accurate memory or it could be merely symbolic, anticipating the post-resurrection Jesus. Both positions have their scholarly defenders. My guess is somewhere between. I’d like to imagine the Transfiguration as an event in Jesus’ life that may not have looked like the picture in the Gospels. I imagine Jesus at prayer. He’s experiencing a kind of rapture. He looks like one who hardly belongs to this world. This may have happened many times. It becomes a story that undergoes a normal process of exaggeration through retelling. Mark adds some symbolic elements, including Moses and Elijah and a voice from heaven. We’ll see those in the next post.

That’s a guess, of course. It enables another guess. Mark has a story about an exorcism. The disciples were not able to accomplish it, but Jesus could. My guess is that Mark consciously placed this exorcism right after an embellished episode of Jesus at prayer.

Looking ahead

My next post will deal with what that “prayer,” that is, the conversation Jesus had with Moses and Elijah on the mountain, may have been about. It will cover the events in the middle between the bookends of the healing miracle that took two tries and the exorcism that only Jesus could do. Those events are Peter’s declaration about Jesus’ identity, the first prediction of the Passion, some teaching by Jesus about discipleship, and the Transfiguration.