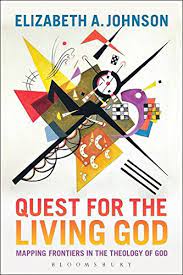

Elizabeth Johnson Maps ‘Frontiers in the Theology of God’

My favorite book store is the St. Vincent de Paul in Madison, Wisconsin. There for a dollar I picked up a copy of Elizabeth A. Johnson’s 2007 book Quest for the Living God: Mapping Frontiers in the Theology of God. I was visiting my daughter, who posed a couple questions. Why does it say God is living? What does “living God” mean? And, Why are there still new things to say about God? Is there anything really new under the sun?

My favorite book store is the St. Vincent de Paul in Madison, Wisconsin. There for a dollar I picked up a copy of Elizabeth A. Johnson’s 2007 book Quest for the Living God: Mapping Frontiers in the Theology of God. I was visiting my daughter, who posed a couple questions. Why does it say God is living? What does “living God” mean? And, Why are there still new things to say about God? Is there anything really new under the sun?

Devouring this book in record time (for me), I found a living God fairly leaping off its pages. This God is deeply involved in every crisis, every issue facing a dynamic, changing world. That world with its various new challenges is the context within which Christians live out their faith and, in consequence, find new things to say about the God in whom they believe. In Johnson’s telling the concept “God” doesn’t float down from heaven in a supernatural zap of revelation but arises from experiences that we call religious. New experiences in a changing world call forth new ways of thinking about God.

New theologies of the living God

After an introductory chapter setting out the ground rules for any new quest, each succeeding chapter addresses a theology, or theologies, arising out of a different setting. The progression is roughly both chronological and spatial, through time and across cultures. It reaches from the world of white male privilege and dominance to the experiences of women and all those “others,” including earth as one of the poor, whom politics and economic systems marginalize.

A partial table of contents

Chapter titles and descriptions will indicate the various contexts out of which new thinking about God emerges.

- Gracious Mystery, Ever Greater, Ever Nearer. The transcendental theology of Karl Rahner faces the challenge of atheism.

- The Crucified God of Compassion. In the face of unspeakable suffering such as that of the Jews in World War II, no abstract theory about the existence of evil in God’s world will do.

- The Liberating God of Life. Liberation theology, originating in Latin America, concerns itself not with the non-believer but with the non-person.

- God Acting Womanish. Women’s experience requires an appreciation for the feminine side of God and a much larger set of symbols for the divine.

- God Who Breaks Chains. Slaves in this country turned the religion of their oppressors into songs of survival and eventual freedom. God, who is black, lives the black experience in Jesus and in the Exodus from slavery in Egypt.

- Accompanying God of Fiesta. Hispanic, or Latino/a, popular religion expresses, through images, charms, processions, fiestas, and devotion to la Virgen, people’s connection to God in lo cotidiano, everyday life. Such spontaneous connections function somewhat independently of a clerical hierarchy

- Generous God of the Religions. In Asia, where Christians make up around one percent of the population, Catholics observe God acting outside the boundaries of the Church. Religious pluralism seems to be part of God’s plan.

- Creator Spirit in the Evolving World. The natural world, at the same time wonderful and tragically endangered, is the setting for eco-theologies of God’s universal presence and agency.

New life for the doctrine of the Trinity

None of the “quests” for the living God was entirely new to me. Yet in each chapter I found insights that I had not known or considered or, frankly, in some cases understood well enough to accept or reject until I read Johnson’s lucid prose. Her exposition of Karl Rahner’s difficult transcendental theology is remarkably clear. So was the coverage of James Cone’s startling insistence that Jesus was Black.

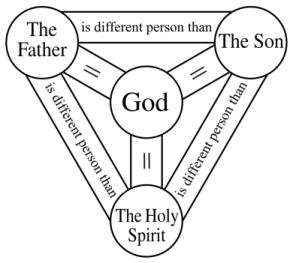

To do justice to the “living God’ of the book’s title, Johnson had to take on Christianity’s signature view of God as Trinity. Nothing says God is alive quite like what Johnson calls “a great ferment … brewing in Trinitarian theology.” (p. 109) It’s a liveliness that went missing in the typical instruction about the Trinity of, say, the last few hundred years. So I anticipated eagerly Johnson’s last chapter on “Trinity, the Living God of Love.” I was not disappointed.

A newly practical doctrine

Each of the chapters in Quest for the Living God deserves a treatment of its own. Future posts will cover at least some of these quests, in no particular order but starting with a post on that last chapter on the Trinity. There I will let Johnson’s text add to and interact with my own growing awareness of new Trinitarian theology. There also I hope to show some ways Catholics can let the doctrine of the Trinity, if rightly understood, influence their practical lives of faith.

A group of Sisters of Providence in Indiana, with a commitment to environmental justice, are doing that and talking about it. They have founded the White Violet Center for Eco-Justice. In 1996 they took back management of their land from industrial farm interests. One sister in a recent article about their sustainable farming project on the EarthBeat site explains: This project

Invites us to develop a spirituality of that global solidarity which flows from the mystery of the Trinity.

May the mystery of the living God, three in one, inspire us all in our spiritualities and lives of faith.