Giving God a story, 5. The last post on Elizabeth Johnson’s Quest for the Living God, Chapter 10, on the Trinity

The previous post in this series concluded with the following take on the Triune God:

God’s inner life resembles the way God has revealed God’s self to us. We have experienced that revelation in Gods affirming, challenging, and freeing actions in the world’s history. God affirms in creating and calling each part of creation good. God challenges through Jesus and his proclamation: “This is the time of fulfillment. Repent and believe in the good news.” And God is engaged in freeing the world from endless, hopeless cycles of growth and decay, love and hate. To that end God chose a people and nourished them with commandments and Sabbath rest. God sent the Son, calling us his friends instead of slaves. God poured out the Spirit, who moves in all these developments. The Spirit “blows where it chooses” (John 3:8) and does new, unexpected things. Of that Spirit we are born again “in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

Love affirms, challenges, and frees. That’s the way with human love, and those created goods must also be present in the creator. That makes for a very active God. It must be God’s nature with or without a created world. God didn’t just achieve those perfections courtesy of the world. But growth is also a perfection and this post will envisage God and world growing together in freedom through challenge in the context of affirming love. I’ll get some help from a theologian beloved by a pope.

A Balthasarian drama

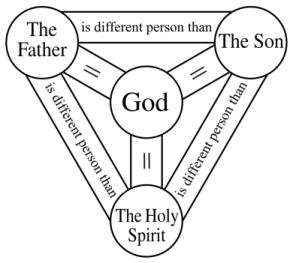

Hans Urs von Balthasar is a favorite theologian of Pope John Paul II. He thinks that the divine life is more dramatic than the static picture I got when I first learned about the Trinity. (See this post) In fact “drama” is one of the words Balthasar uses to describe that life. (Maybe that explains John Paul’s affection for Balthasar. This pope was very much involved in theater at an early point in his career.)

There’s a real story in God that includes the best parts of human love—surprise, excitement, growth in relationship with another. The modern world, with a push from Darwin’s theory of evolution, doesn’t see anything wrong or imperfect in change. Growth is one of this world’s perfections, something the ancient Greeks, with their static worldview, couldn’t fathom. Balthasar says that God

… must include in some genuinely analogous sense all the perfections of love such as life, movement, even mystery and surprise. To say otherwise would be to ascribe more perfection to human love than to God’s love. (Nicholas J. Healy, The Eschatology of Hans Urs von Balthasar, p. 81; quoted in Rodney A. Hosare, Balthasar: A Guide for the Perplexed, p. 63)

I want to tell a Balthasarian story of God’s love. I’ll start the story with a favorite Bible passage, which actually comes in the middle of the story; so this story will have a flashback.

1. Affirmation: God empties God’s self and affirms an Other.

Christ Jesus … though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather, he emptied himself, Taking the form of a slave…. (Philippians 2:6-7)

This is a Christian hymn that Paul quotes. The Christian community must have known it even before Paul wrote. And Paul is our earliest written source, so the hymn is very early. If we learn what God is like by discovering what Jesus is like, then this hymn must tell us something about God.

When Jesus, as God the Son, “emptied himself,” he was actually imitating the Father’s self-emptying. God’s empties God’s self in a gift to another. That other is the Son, to whom God, as Father, offers everything that God is, without conditions, without expecting anything back. This is the inaugural affirmation. It precedes, in the order of essence rather than time, all other affirmation, whether eternal, within the Trinity, or temporal, as in the world’s creation.

The Son in gratitude returns the gift of self to the Father. That eternal return gift is precursor and model for the time when the Son, as the hymn says, empties himself of divine prerogatives. In the incarnation Jesus obeys freely and perfectly the will of the Father.

Much has been written recently about God’s kenosis, i.e. self-emptying. (A good example is The Emptying God, subtitled “A Buddhist-Jewish-Christian Conversation.”) Balthasar, in Howsare’s paraphrase, says:

In Jesus’ surrender of himself on the cross … we catch a glimpse of the Father’s eternal surrender of himself to the Son. (Howsare, p. 137)

And:

The person of the Son … consists precisely in his utter gift of himself to the Father, and vice-versa. (Howsare, p. 133)

A kind of suffering in God

We’re in the flashback part of the story, actually a flash into eternity. God the Father abandons God’s self, gives God’s self away, in the eternal life of the Trinity. Balthasar sees this self-emptying of God as a kind of suffering. Not

… suffering as an evil, the suffering we experience when we lack something. Rather, what he has in mind is the suffering involved in kenotic [self-emptying] love. The emptying of the Father’s heart in letting the Son proceed. (Thomas G. Dalzell, “The Enrichment of God in Balthasar’s Trinitarian Eschatology,” in Irish Theological Quarterly 2001; 66; 3, p.8.)

I’d compare this suffering to a mother watching her child “leave the nest” to go off to kindergarten or college. It’s a kind of suffering but only out of an abundance of love. God parts from God’s own heart.

It has occurred to me, when thinking about God’s power, that sometimes God is powerless. When it comes to really important things, like turning a sinner away from sin, maybe God can’t do much except suffer. Here, I think, Balthasar adds some credibility to that suggestion. In some “genuinely analogous sense,” Balthasar says, God does suffer. It’s a “suffering” whose end is the affirmation of all otherness, including otherness within the Trinity.

2. The challenge: A surprise in God

The Son receives the total gift of the Father. Since the Father’s identity is self-emptying love, that is the Son’s identity, too. Thus the Son eternally offers back the Father’s gift. In spite of their likeness in every detail, the Son and the Father keep their own identities because the Son never forgets that his identity is the Father’s gift. Traditional theology clarifies: The Son is everything that the Father is except being Father, and the Father is everything the Son is except being Son. The Son rejoices in being “begotten” of the Father.

Now flash forward one eternity plus 13 or 14 billion years. Think of a human mother cradling her baby in her arms. Now think of that first smile, a sign of the baby’s gleeful acceptance of and dependence on that encompassing love. Think of the mother’s rejoicing in the happiness of the baby. That is a joy that the baby in its sheer helplessness and blissful dependence gives to the mother.

Balthasar says God’s joy is like that. It includes surprise like the surprise we feel at a baby’s first smile. Even if, Balthasar says, the Father knew in advance what the Son would do, the joy in the Son’s return gift is more than the Father hoped for “in his wildest dreams” (Balthasar’s words, but I lost the reference).

Another surprise

For one who grew up with traditional Catholic theology, there’s another surprise. This back and forth in self-giving — mutual giving and receiving — between the Father and the Son seems right to me. But it’s not what Catholic theology has long taught. The Father generates the Son, and the Son is generated by the Father. (The Creed refers to begetting; the Son is “begotten, not made.”) It’s active on the part of the Father and passive on the part of the Son. Traditional theology sees no passivity in the Father. But here I’m saying the Father receives from the Son, even that the Father is surprised by the Son’s gift.

Is it taking away something from the Father to say that the Father receives something from the Son? No, Balthasar would say, for a reason he has often mentioned. Every created good must have a counterpart, an analogue, in God.

Certainly the ability to give and receive [Balthasar’s emphasis] that is found at the human level of worldly Being should be understood as higher than the relatively non-relatedness of, say, rocks. It would be strange, in short, if God were more like a rock in its inability to receive than the human person in its ability to do so. (p. 124)

God the Father receives from the Son. Balthasar also sees in God’s relation to the world a receiving as well as a giving. (p. 124) (I was once taught that God doesn’t have any real relationship to the world. Oddly, the world would be related to God but not God to the world.) I end this essay with the less traditional Balthasarian suggestion. God and the world grow together.

Growth

Think again of the mother and smiling child. Think how the child helps her to be a better mother simply by accepting her as mother. The mother needs to grow some in response to one of the more delightful challenges a person can get, a child’s smile.

God doesn’t stay the same either. The hymn that Paul quotes says Christ

… emptied himself — being born in human likeness ….

I don’t imagine this emptying happened for the first time at Jesus’ incarnation. From all eternity the Son renounces all claim to independent status, surrendering to the Father that claim of ownership of self. The Son joyfully accepts sonship, smiles at the Father, and the Father grows as a father. Now it’s the Father’s turn to shine even more brightly on the Son, prompting an even richer response from the Son. There is an eternal mutual enrichment going on between Father and Son.

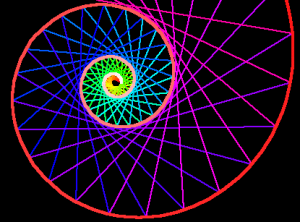

The life of mutual self-giving, mutual other-enrichment, mutual growth, is not an eternal circle but a spiral.

3. Freedom: The spiral, the opening, and the bridge

I can imagine a spiral in two different ways. There’s the spiral of pennies rolling around in one of those geometric, conical basins that you sometimes find in a museum. If there are two pennies, they spiral down, faster and faster, until they meet at the hole in the center. As Father and Son take enrichment from each other, do they gravitate toward each other, become more and more alike—like one hears about some dogs and their owners? Are they aiming for, though perhaps never reaching, the point where they are identical? That way love dies! Love requires difference, the ability to surprise, in other words, real persons.

The other kind of spiral widens continually outward. It is the spiral that love keeps opening and bridging over. Human persons, attempting at loving, become truer lovers as they learn to affirm each other, not as an images or approximations of themselves, but as really other. Love challenges the other and receives a challenge from the other to change and grow. Finally love plants in the heart of the other the freedom to affirm and be affirmed, to challenge and be challenged, to touch and be touched.

That freedom matures into a power, not to do whatever one wants, but to grow into what one truly is. It is mature enough to receive as well as give, to realize that one is not a person on one’s own but only in relationship. The bonds holding this love match together only grow stronger as persons find their more and more distinct – and true — “personalities.” I suggest that we can find, in some reasonably analogous form, even that last concept in the divine Persons, growing as distinct personalities in their eternal love.

Room in God for a created world

The widening spiral of God’s love opens within deity a space big enough to contain a temporal, created world. God’s self-emptying gift, making room within the totality of being for an other, extends to what is not God, to what didn’t have to be.

Scripture allows us to imagine Persons in a divine Trinity as affirming, challenging, and freeing as they relate to the world and the human community. In fact, each of the three seems to be about all three of these movements. The movements, however, have their preferences. Affirming seems to home in mostly on the Father; challenging on the Son, and freeing to dare new things on the Holy Spirit.

During the course of the world’s history, the Son, continuing his original separation from the Father, identifies with the world in its distance from God. The Bible shows how this suffering, divine love challenges and even confounds us. It favors and holds close all those whom we keep at a distance. Most astoundingly, we discover that our own humanity—not just an abstract ideal but our particular sinful condition—is taken up into the divine love in Jesus.

A bridge between God and people

Paul calls our distance from God “flesh.” The author of the Gospel of John says Jesus bridges that distance:

The Son of God “became flesh and dwelt among us.” (John 1:14)

Jesus experienced the ultimate distance from God on the cross:

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34)

It was not only Jesus’ humanity that was separated from God on the cross, with his divinity hiding, keeping itself safe. Jesus’ divine and human person suffered and died on the cross. But the resurrection bridges over even that distance. In Jesus’ resurrection all distances are bridged over.

On earth a bridge connects two land masses, but it doesn’t eliminate their differences. We become more human, not less, as we are taken up into the divine love. Lovers become more unexchangeably themselves in the ever widening spiral, and love binds them together all the more strongly.

God’s community as Trinity is the ultimate model for human community and human community’s ultimate goal. Unity becomes stronger as we accept differences, relish them, and let them flourish in a community’s widening circle of love. In the Spirit and through the Son—always through the Son, who identifies with us—even we, and the world with us, approach the Father to add in new ways to the surprising drama of God’s love story.