Giving God a story, 3: The third of five posts on Elizabeth Johnson’s Quest for the Living God, Chapter 10, on the Trinity.

In this post I’m dialoguing with and sometimes taking issue with, Elizabeth Johnson on the doctrinal issue of three Persons in one God, the Trinity. But there’s no disagreement here with her conclusion concerning the low point in the development of trinitarian theology, the subject of the last post. Johnson concludes:

No wonder [the Trinity] has not inspired Christian life and piety with any great dynamism…. The breach between the founding experience of salvation and its expression in theologies of the Trinity needs to be healed. (p. 209)

That healing starts with Scripture. The Bible bears a triple witness to God’s saving action:

- in accompanying and never leaving the Hebrew people,

- in initiating the Kingdom of God through the work of Jesus,

- and in the presence of the Holy Spirit among Jesus’ followers after his death, resurrection, and ascension.

Johnson insists – and I think the early Church must have experienced it – that to this triple witnessing of God’s saving work correspond real distinctions in God. The witness that Scripture gives to the experience of believers reveals God as God really is. It’s not a mask or a dumbed-down, human-level version behind which a genuine deity lies in awesome isolation. This point doesn’t let us think that, maybe, the Trinity is just three ways God acts toward us or appears to us. Or maybe that about who God really is even revelation doesn’t allow us to say much. No, says the Church, God reveals God’s very self.

Three Persons and language about God

Whether we say little or much about God, the language we use has its limitations. Even after revelation God remains too awesome for human comprehension. Language always fails to grasp God’s essence. This is not surprising. Often the words that we use point to something they cannot reach. Poets and lovers know this. It doesn’t stop them from speaking their love in pointers.

The word “person” in the formula “three Persons in one God” is like that, a pointer, not a literal account. Johnson thinks of the numbers “three” and “one” in the same way. But I’ll get to the strange trinitarian math later.

Johnson worries about the danger of reading our own concept of person into the three Persons of the Trinity. She mentions a suggestion by Rahner that we drop “person” for a while in favor of something like “distinct manner of subsistence.” Or maybe we should just say that there are three x’s in God, as another theologian proposes. (p. 312)

Personally (!), without “person” I would be missing too much. I can’t relate to an x or philosophical jargon. “Distinct manner of subsistence” could apply to a rock.

Persons and a difficult word in the Creed, ‘consubstantial’

So I continue saying “three persons” in reference to the triune God. But I realize that I don’t know very well what a person is. One thing I seem to understand, perhaps with help from new thinking about the Trinity, is that human persons exist only in relation to other persons and things. (Traditional societies probably always knew this.)

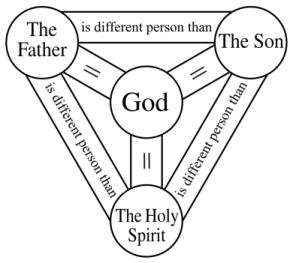

In God’s case, unlike persons in our experience, the way the divine Persons relate to each other is the only difference between them. The Father is exactly like the Son except for being Father, not Son. And vice versa. Likewise for the Son and the Spirit and for the Spirit and the Father. Other than that, i.e., apart from their relations to each other, the three Persons are substantially the same. The new translation of the Creed at Mass says it: The Son is “consubstantial” with the Father. The same goes for the Spirit. The three Persons are consubstantial with each other. That’s how Christians can say, Three Persons but one God. But I feel like I need to understand the “substantial” bit better and the strange three-in-one part. I’ll look at substance and relations through an analogy. But first the math.

The strange trinitarian math

Here’s the strange math I mentioned earlier. Christian doctrine says:

- The Father = God; the Son = God; the Spirit = God.

- The Father ≠ the Son; the Son ≠ the Spirit; the Spirit ≠ the Father.

- But there is only one God.

- So, 1 Person + 1 Person + 1 Person (all different from each other) = 1 God.

Johnson basically gives up on understanding it. She says the numbers one and three “do not refer to numbers in the usual sense.” And,

To say that God is one is to negate division, thus affirming the unity of divine being: there is only one God. To say that the “persons” are three is to negate solitariness, thus affirming that divine being lives in communion. (p. 213)

Yes, but, it seems to me the numbers also mean exactly one and three – one God, no more; three Persons, no more or fewer. Now, how can 1 + 1 + 1 = 3?

An analogy

Through my town of Springfield, Minnesota, there runs a highway known as U.S. 14. Actually this road has two names: U.S. 14 East and U.S. 14 West. My cellphone navigator always makes sure I know whether I’m on 14 East or 14 West. Now, 14 East is exactly like 14 West except it’s East, the opposite of West. And 14 West is exactly like 14 East except for being West, the opposite of East. The two are different in their relation to each other; they’re opposites. And that’s the only difference. They’re the same substance. (There’s only one road surface.) So:

One U.S 14 East plus one U.S. 14 West equals, substantially, one highway.

It’s like what we say about the three Persons in God. Relative to each other, the three are all different. And that’s the only difference. Substantially they are one God. They are consubstantial with each other.

My analogy isn’t a perfect fit, like all analogies. U.S. 14 East isn’t exactly the same as U.S. 14 West because cars going east usually travel in a different lane from cars going west. Our minds have trouble thinking of relations without something, some substance, in that relation. The substance seems to come first; the relations are added on more or less accidentally and could have been different. The road could have been going north and south instead of east and west.

I still don’t really understand the Trinity.

The Trinity, in a way that we can’t imagine, subverts the order of substances and relations. In the divine Persons relations take over the role substance usually plays. The Father isn’t some divine thing (substance) that happens to be a father. The Son isn’t an exactly similar divine thing but different in that it happens to be a son. Likewise for the Spirit. I think that is what Augustine is getting at in this passage, which Johnson quotes:

When it is asked, therefore, what the three are or who the three are, we seek to find a generic name which may include the three together. But we come across none, because the excellence of divinity transcends all the limits of our customary manner of speaking. For God is thought more truly than can be uttered, and exists more truly than can be thought. (p. 212)

Only, I’m not sure God really is thought more truly than can be uttered. It seems to me our stammerings about God, Trinity, Three Persons in One God, may be true enough even if we can’t think them through. As for that, i.e. thinking through, just try answering Augustine’s question. What are the three Persons? Is there a “generic name,” a description, that fits all of them? It can’t be “God” because that’s not a genus or a description; it’s the name of the One we pray to. It can’t be small-g “god,” which is a genus, because then we’d end up with three gods.

As I said, I don’t understand the Trinity. But the language of one God, one substance and three Persons different in their relations to each other, makes it possible to keep a conversation about God going.

A story with action

Johnson insists that such talking about the three-in-one God must describe a God in action,

… not a static being but a plenitude of self-giving love, a saving mystery that overflows into the world of sin and death to heal, redeem, and liberate.

And she says, our language about God’s inner life “must function directly with respect to God’s redemptive work.” (p. 214) That goal is what Johnson attempts in the rest of her chapter on the Trinity.