The first of five post on Elizabeth Johnson’s Quest for the Living God, Chapter 10, on the Trinity.

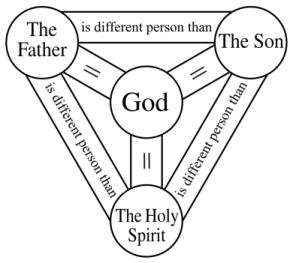

God is perfect love. That must mean God didn’t just fall in love after creating a world to fall in love with – like Pygmalion falling in love with a statue he made. But what else is there for God to love? Maybe God is in love with God’s own self from all eternity, like another mythical Greek, Narcissus. That doesn’t seem right either. The Christian doctrine of the Trinity improves on the Greek stories by seeing in God’s own being the otherness of the object of genuine love. The Father is not the Son, who is not the Spirit, who is not the Father. Three Persons, and it’s only one God, a paradox that comes into a later post in this series on the Trinity.

So it’s not like Narcissus, but there’s another problem with the Narcissus “love” story that thinking about the Trinity ought to avoid. Narcissus doesn’t do anything about his love except sit around and stare and eventually pine away. What kind of love is that? Now I’m wondering: Does anything actually happen in the Trinity’s perfect love story? What kind of love characterizes the three-Person God, who conceivably might not ever have created a world to love, but still would be, somehow, loving?

Renewal of theology on the Trinity

The doctrine of the Trinity has become a fruitful area for Christian scholars to contemplate anew in the past half century or so. This is the last of the many contemporary issues in theology that Elizabeth Johnson tackles in her 2007 book Quest for the Living God: Mapping Frontiers in the Theology of God. (I wrote an introduction to this book some months ago.) Johnson’s book accomplishes what its subtitle suggests. It surveys with lucid explanations new developments in Christian theology. Her final chapter, “Trinity: The Living God of Love,” has helped move my own thinking on the Trinity forward.

A renewal of thinking about the Trinity began with the realization that this central doctrine didn’t have much impact on Christian piety and life. As long ago as the late 1960’s, Karl Rahner laments that

… despite their orthodox confession of the Trinity, Christians are, in their practical life, almost mere ‘monotheists.’

And that

… should the doctrine of the Trinity have to be dropped as false, the major part of religious literature could well remain virtually unchanged. (The Trinity, p. 10-11)

The Trinity I thought I knew

I learned early on that the Trinity is impossible to understand and that belief without understanding is not only OK but even a Christian virtue. Like, I guess, the queen in Alice’s Wonderland, who could believe six impossible things before breakfast.

Oddly enough for something no one could understand, I was then given a neat explanation. Johnson nails the irony here:

While it gave lip service to divine incomprehensibility, Catholic neo-scholastic theology … engaged in luxuriant technical description of God’s inner self-differentiation ….” (p. 207)

Quite a bit less technically, the version of the doctrine I learned went like this:

God is perfect in all ways; hence, God’s knowledge is perfect. God knows God’s self, and this knowledge is so perfect that it is an exact copy of God. (This part seemed to make sense.) That copy is another person, God the Son, whom the Father loves. The Son looks back at the Father and returns that love. The Father and the Son love each other with a love so profound that this love is a third person, the Holy Spirit. (This part always seemed less convincing, but I supposed if knowledge can be a person, so can love.)

This, I learned, is what God is like whether or not God created anything. God did create a world, and the Son came to this world and declared us his brothers and sisters. We have been adopted into the divine family of love that existed from all eternity. (I always liked that part of the theory.)

Perfect and changing?

It’s a very calm Trinity, and it answers well to a Greek concept of perfection. The ancient Greeks allowed no possibility of change in their imagination of perfect being, or God. Any change would be a step down from perfection. God, for the Greeks, would have to be unchanging. Not much story in Aristotle’s god.

The three eternally loving divine persons, in the Trinity as I learned it, don’t seem to be doing much, either. They hang around eternally staring at each other, God staring at God’s own self in the first place. I now have to wonder what I ever found attractive in a divine trinity described so bloodlessly.

Even my favorite part of the theory, our participation when we enter fully into that family of love, has a strangely sedentary name. We get to sit and enjoy the “beatific vision.” As someone who has trouble sitting still for any length of time, I’m hoping my eternal rest is more active than that. (See note below.) There’s knowledge and love, but here knowledge gets first place. Love seems to be a variety of knowledge.

A look ahead

What I like about Elizabeth Johnson’s chapter on the Trinity is that she finds ways to give God a story with some action in it. Actually she tells two stories. The first is a story of the Church’s adventures and misadventures regarding the doctrine of the Trinity. There’s a beginning in the trinitarian experience and language for God among early Christians. The story reaches a defining moment with some early theologians, the “doctors of the Church.” Then it falls away into ever more abstract and irrelevant speculations. Most recently a new forward movement is happening, and it begins by retrieving the more authentic, earlier approach. Johnson’s first story, on the adventures and misadventures of the doctrine of the Trinity, will be the subject of my next post, Part 2.

The second story will depict language trying not to remain silent about the mystery of the Three-in-One. Our language necessarily falls short, but silence isn’t an option. That will be Part 3. A fourth post will take up Johnson’s detailing of some recent thinking about the Trinity. This series will end with more thoughts about the love story that is the Trinity.

Note: Bernard McGinn references the Eastern mystic Gregory of Nissa, who says the experience of heaven is epektasis, meaning “stretching forth always.” (“‘Lived from the Heart,’ An interview with Bernard McGinn” by Kenneth L. Woodward in Commonweal, January 2022, p. 35)