Giving God a story, 4: The fourth of five posts on Elizabeth Johnson’s Quest for the Living God, Chapter 10, on the Trinity.

Elizabeth Johnson has taken us through some adventures and misadventures of the doctrine of the Trinity. She started with Karl Rahner’s and, much later, my suspicion that the doctrine was being understood, if at all, in a way that made it irrelevant to piety. The way to avoid such abstraction, she said, is to start with the experience of the early Christians. They experienced one saving God; that was their Jewish heritage. But they also experienced salvation in the undeniable person of Jesus and in the presence of the Spirit of Jesus and the Father.

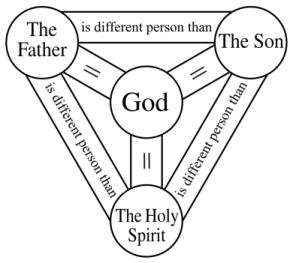

Eventually the Church had to develop a doctrine of the Trinity, using the categories of substance, person, and relation that Greek thought made available. It was in no way an explanation of what Christians believed. More like a doctrinal fence around the Church’s three-fold experience of salvation: reconciliation to the Father through Jesus in the Holy Spirit.

Besides connecting to our experience of salvation, Johnson thinks our language about the Trinity ought to have a trinitarian flavor. What this means, as she carries it out, is that we shouldn’t be thinking too long about any one Person of the Trinity without considering each of the others. She writes of three trinitarian “inflections.” I think of them as points of view. The theological inflection thinks about the Trinity from the point of view of the Father. The Christological point of view does so from the point of view of Jesus, the Son. The Spirit, or pneumatological, inflection thinks from the point of view of the Spirit.

The Theological inflection

The Jews worshiped God with the unpronounceable four-letter name YHWH. Scholars call it the tetragrammaton, “tetra” for four. Most often we translate it “Lord.” This incomparably unique One was Jesus’ God. In Jesus’ life it was this Lord’s action that accomplished everything that mattered. I think of Jesus’ miracles. He did not attribute them to his own power but said, “the Kingdom of God has come upon you.” (Luke 11:20) Johnson notes how Jesus often uses the “divine passive.” Mourners “will be comforted”; believers “will be saved”; to those who knock “the door will be opened.” Especially, Jesus prayed and taught to his disciples to pray, “Hallowed be thy name. Thy will be done.” In every case, Johnson says, it is YHWH God who is the actor. The Spirit too, whom Christians vividly experienced, is “identified [in Acts 5:9] as the ‘Spirit of Lord, that is, the Spirit of YHWH.” (p. 217)

The God of the New Testament doesn’t nullify or replace the God of the Old Testament. The theological inflection “requires that the whole history of God with Israel flow into Christian understanding of the triune God.” (p. 217)

The Christological inflection

The Christological inflection follows a theme that I have applied elsewhere. We don’t know who God is first and then say, That’s what Jesus is. We know Jesus, including his willing suffering for us, and allow our concept of God to arise from that. Johnson says,

Unlike the name YHWH, which is mysterious … the second inflection identifies God in a simple, fixed, and pronounceable form …. (p. 217-18)

Jesus with the very pronounceable name also uses a name for God that is easy to say: Father.

Johnson doesn’t refer to the Christological hymn in Philippians 2: 5-11, but it seems to apply. This very early Christian hymn attributes to Jesus “the name that is above every name.” I think right away of the tetragrammaton. The hymn proceeds:

That at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord to the glory of God the Father.

“Lord” in English (in Paul’s Greek “Kyrios”) is the usual translation of YHWH. I once though that “Jesus Christ is Lord” was the climax of the hymn and that the last phrase about the Father was a kind of let down. It even seemed out of place in a hymn meant to glorify Jesus. But the hymn really glorifies God the Father. It is the Father who bestows on Jesus the “name above every name.” And the ending phrase is the hymn’s climax. Everything about Jesus glorifies God the Father.

As the Spirit is the Spirit of the Lord, YHWH, so the Spirit is the Spirit that Jesus breathes on the apostles and sends on the Church once he has ascended to the Father.

The Pneumatological inflection

It seemed to me that Johnson was giving the Holy Spirit less than due attention in the first two inflections. She makes up for it here, possibly the most innovative part of the Chapter on the Trinity.

Johnson uses analogies to describe the place of the Holy Spirit in relation to Father and Son. It is like the sun (father), the sunbeam (Son), and the suntan (Holy Spirit). Or the spring, the river, and the irrigation ditch. Or a tree’s roots, trunk, and fruit. The Holy Spirit is where the work of the Father mediated by the Son reaches its target in the faith and lives of people. There’s a kind of biblical chronology to them: first the God of the Old Testament, then the earthly career of Jesus, then the pouring out of the Spirit “on all humankind” as the prophet anticipated (Joel 2:28). Nothing in these analogies is really new.

Johnson says the pneumatological inflection does give the “service of the Gospel” a new look because

… through the centuries [it] enlists forms of speech characteristic of the discourse of peoples, tribes, and nations….

Theologians of our time sees a multitude of new ways, always in threes, of thinking about the Trinity. They use personal and non-personal imagery. Johnson summarizes several of these and adds two of her own. I include some of them here, with underlining to make it easier to see that each one has three parts. I added some comments.

Non-personal images of the Trinity (p. 219-220)

- John Macquarrie uses one of my favorite ways of thinking about our creating God – letting-be. God in this three-fold image is Primordial Being, or source; Expressive Being, mediating this letting-be; and Unitive Being, closing the circle in “a rich unity in love.”

- I’m not so fond of the very common image of the closing circle. Making unity and love the specialty of the Holy Spirit is a common Western idea. Eastern theologians, whether Catholic or Orthodox, attribute those energies to the Father.

- Gordon Kaufman sees divine absoluteness, divine humaneness, and divine presence in the three-dimensional God.

- One definition of absolute is “independent, not in relation to other things.” God’s “humaneness” contrasts interestingly with that. The Holy Spirit, here called “presence,” brings the Absolute close so that it “relatives all idols,” our fake absolutes. Divine humaneness closes in to judge “all human inhumaneness.”

- Paul Tillich sees creative power engaging our finiteness, saving love overcoming our estrangement, and ecstatic transformation sorting out and purifying our ambiguous existence.

- We are finite, yet drawn toward the infinite; sinners, yet loved; a mixture of good intentions and flawed follow-through awaiting transformation.

- Lastly Johnson gives her own image, the shape of the life-giving DNA molecule. She imagines three strands instead of DNA’s two. The three twirling strands combine and recombine to “bring forth, heal and repair, and create ever-new forms at the heart of the universe.”

- I’ve noticed that in the Bible, whether Old or New Testament, whenever the Spirit is present, something new is happening. The Spirit hovers over the waters at the creation. The dove, symbol of the Spirit, flies forth from the Ark at the world’s renewal after the Flood. The same dove symbol hovers over Jesus at his baptism, the beginning of his ministry. The Spirit descends in wind and flame at Pentecost, the beginning of the Church. Johnson’s “spirit” strand of DNA is true to the Bible.

Personal images of the Trinity (p. 220-221)

- Walter Kasper sees in the Trinity a source (giver), a mediation (receiver and giver), and a term (receiver) of love.

- This image translates into personal terms older images like that of the sun, the sunbeam, and the suntan.

- Peter Hodgson imagines Father, Son, and Spirit as the One – who Loves – in Freedom “in the midst of the world’s fractured history.”

- Translating “in Freedom” as “Freely,” I can see here a departure from the use of nouns for the three Persons. Here we have an indefinite marker (“One” is almost like X), a verb (Love), and an adverb (Freely). This is an active God, even grammatically.

- Herbert Mühlen sees in God the I, Thou, and We of love.

- Again the Holy Spirit is tasked as the unifier in God. I don’t know why this should be.

- Johnson also gives her own image. This time she is deliberately countering the usually too-masculine God. She appeals to the feminine biblical image of “Wisdom-Sophia.” Wisdom “creates, redeems, and makes holy the world.” She is Mother Sophia (source and Holy Wisdom herself), Jesus Sophia (incarnate wisdom), and Spirit Sophia (mobile, gracious presence).

- I wonder about the use of the same image, wisdom, for all three Persons. It seems like what St. Augustine said we can’t do, find a common essence for the three. (See last post.) Three instances of wisdom is too much like three instances of the genus tree. You have three trees in the one case; three gods in the other.

A look ahead

God exists with an inner life that is analogous to the way God has revealed God’s self to us. We have experienced the affirming, challenging, and freeing movements of God’s actions in the world’s history. God affirms in creating and calling each part of creation good. God challenges through Jesus and his proclamation: “This is the time of fulfillment. Repent and believe in the good news.” And God frees the world from endless, hopeless cycles of birth and death, growth and decay, war and peace, love and hate by choosing a people and nourishing them with commandments and Sabbath rest; by sending the Son, through whom we become friends instead of slaves; and by pouring out the Spirit, which “blows where it chooses” (John 3:8) and does new, unexpected things. Of that Spirit we are born again “in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

Affirming, challenging, and freeing are three ways God loves the world. I suppose this would be the pneumatological inflection again, finding another way to imagine the Trinity as it works in the world. In the next post I imagine the same affirming, challenging, and freeing love in God’s own life in Trinity.