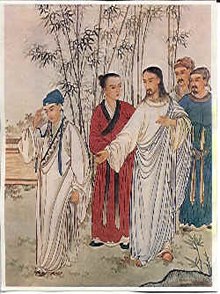

A rich man asks Jesus how to inherit eternal life. It would seem to be a time for Jesus to come up with some new rules. The laws that the man claims to have followed “since my youth” don’t satisfy. But Jesus didn’t need new laws to support his vision of the God he recognized as Father of the poor. Jesus didn’t replace the old Law, the Torah, with a new one or even upgrade the old Law. What Jesus read in the Law was sufficient for his purpose. But it depends on how you read.

At one point Jesus asked a scribe, “What is written in the Law? How do you read it?” It’s not two different ways of asking the same thing, William R. Herzog II insists. Jesus’ reading of the Law differed from that of the rich man and his ilk.

This is the fifth post on Herzog’s Jesus, Justice, and the Reign of God. Earlier posts in the series are:

- The Historical Jesus and the Transcendent God in the Work of William Herzog

- Context Group Continues the Long History of Witnessing to Jesus

- Jesus Heals a Paralytic and Opens a Temple-Free Zone of Grace

- The Temple, Jesus, and the Little Traditions of Village Life

The historical rich man and Jesus

Herzog considers that the story of the rich man – we don’t know his name, so I’ll call him Rich Man or Rich – might have originated with the Church. But the story is early, probably from before the Gospel of Mark. It fits well enough into Jesus’ circumstances and the themes of his ministry. It likely is an actual memory of the historical Jesus, Herzog believes. (p. 167)

Besides fitting thematically into Jesus’ history, two elements in the story seem too odd not to be historical. First, Jesus objects to being called good. It’s harder for me to imagine Christians making that up than to imagine the Church remembering that Jesus didn’t want to be called good. Jesus also quotes the Decalogue but misses half of the Ten Commandments, the more important half. I don’t think the Church would have made that up either, but they might easily remember Jesus leading Rich Man on with a partial list of commandments.

Thinking of the encounter as historical makes speculating about Rich’s mind fair game. That’s what Herzog does, and I will do some speculating on my own. As a first step, notice the man’s mindset in the story that follows – a bit overconfident to start, sad at the end.

The story, Mark 10:17-22

As [Jesus] was setting out on a journey, a man ran up and knelt before him, and asked him, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?’

Jesus said to him, “Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone. You know the commandments: ‘You shall not murder. You shall not commit adultery. You shall not steal. You shall not bear false witness. You shall not defraud. Honor your father and mother.’”

He said to him, “Teacher, I have kept all these since my youth.”

Jesus, looking at him, loved him and said, “You lack one thing. Go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

When he heard this, he was shocked and went away grieving, for he had many possessions.

A confident rich man greets Jesus

Various scholars have seen an important detail in Rich Man’s greeting, “Good Teacher.” Herzog and others from the Context Group see it as a hostile challenge. In a zero-growth society with all goods limited, whether material property or honor, one person’s abundance comes at the expense of another person’s want. In such a society,

… compliments indicate aggression; they implicitly accuse a person of rising above the rest of one’s fellows at their expense. Compliments conceal envy, not unlike the evil eye. (p. 159, quoting Malina and Rohrbach, Social-Science Commentary, p. 244)

But other scholars have imagined not aggression but flattery in “Good Teacher.” (Bailey, Through Peasant Eyes, p. 162) Rich Man would be looking for an answering compliment, something like “Noble Sir,” perhaps. I’m looking at the end of the story where the man goes away “grieving.” If he were hostile at the beginning, I don’t think he would be sad at the end. Anger or frustration seems more likely. So, in Rich’s intention, flattery seems more likely than hostile challenge. I’m going with Bailey’s suggestion.

Jesus might still feel some conflict in the greeting. Calling someone good implies a right to evaluate a person’s character. Rich must rate himself at least as highly as he rates Jesus. None of the humble poor ever call Jesus good, even when they come begging for good things from him. There is as much dishonor as honor in Rich Man’s compliment. Jesus rejects it, along with the man’s self-concept: “No one is good but God alone.” It’s not Jesus’ humility showing, and Jesus is not just giving a free lesson on how good God is. He didn’t spout such obvious truths. Jesus cleverly fends off the challenge of Rich’s implied superiority.

Jesus’ two-part answer

Jesus intends to challenge Rich Man, but he starts out easy. He names several of the commandments, but only the ones that the man thinks he has kept. He hasn’t literally killed or robbed anyone. He’s been careful not to perjure himself in court. And he’d never commit adultery. (What would people think!) With his respectable life and his high standing in society, he has honored his parents. (In return, of course, he expects a decent inheritance.) The man claims to have kept all of these commandments. Jesus’ mention of defrauding, though, may have given him pause. It’s not one of the commandments.

Mark says Jesus looked at Rich and loved him. That’s unusual. I don’t know of any other place in the three synoptic gospels where Jesus is said to love somebody. That’s another reason I don’t think the man was deliberately hostile – just confused. Like the rich class in general, he thinks his standing in society is a sign of his standing with God. He thinks eternal life is his to “inherit” (his own word). As long as he’s careful about a few rules, that is. So he goes to Jesus to make sure he’s not missing anything. But Rich Man has mistaken the meaning of the five commandments he thinks he’s kept.

“You lack one thing,” Jesus says. I imagine Rich wondering which of the other five commandments Jesus will bring up. He’s probably going over the list in his mind and making sure he has an answer for each one. But it isn’t a single commandment Jesus means but the remaining five altogether, summed up in one instruction:

“Go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

Commandments Jesus didn’t mention

The commandments Jesus left out are numbers one through four and ten (in one of the ways of numbering them) from Exodus 20:1-17:

- Have no other gods before Yahweh.

- Make no idols.

- Don’t make wrongful use of God’s name.

- Keep the Sabbath Day holy.

10. Do not covet anything that belongs to your neighbor.

Coveting could be anyone’s issue. The first four commandments, on the other hand, relate directly to God; and, indirectly, they have a lot to say about the life of the rich. Let’s look at these four again:

- The first commandment comes with a commentary, which Rich Man knows well: “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” It points back to the Exodus story. God formed a people out of former slaves and gave a land to those who had no land of their own. God’s gift was to the whole people of God, not just the rich. God is not well honored by the common usurious practice that transfers land from the poor to the rich. The man in the story had “many possessions.” That meant land, not yachts or antique collections.

- The second commandment forbids bowing down to anyone or anything that is not God. Among these idols is mammon, a synonym for wealth. It’s a deservedly pejorative synonym – “mammon of iniquity” – as Herzog repeatedly shows. (See this post, for example.) In Palestinian economics, service often went to mammon rather than God. Of the rich man Herzog says, “In short, his very life was a violation of the first two commandments.” (p. 164)

More commandments

- The third commandment honors God’s name and forbids, in Herzog’s words, “lifting up God’s name to nothingness.” (p. 164) That’s what the rich did when they attributed their wealth to God’s blessing. God, who meant the blessing of land for everyone, does not bless wealth gained by appropriating the land of the poor.

- The fourth commandment takes one back again, all the way to the beginning, when God created the world. God rested on the seventh day. One thinks of God’s gift not only of the created world but also of Sabbath rest. Scripture specifies to whom this rest is given. Not just those who can afford some leisure time, but “you, your son or your daughter, your male and female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns.” (Exodus 20:10) The rich prided themselves for following the meticulous rules for keeping the Sabbath rest. But this “leisure of the few was constructed on the endless labor of the many.” (p. 164)

Restitution, not charity

Jesus says, “You lack one thing. Go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

I’ve always read this as a recommendation, not a command and certainly not on a par with the Ten Commandments. But that’s my own fear of God’s making similar demands on me. Nothing in the story suggests that. Rich Man’s question is about what is necessary for eternal life, and Jesus answers the question.

In gaining his wealth the rich man has violated practically all of the Commandments. He has …

- put money before God, making an idol of it,

- profaned God’s name by priding himself on enjoying God’s favor,

- prevented many others from enjoying the Sabbath rest,

- consigned the poor to an unsustainable life,

- appropriated land that God meant for everyone, stealing from God and the poor,

- entered into loan agreements with farmers under false pretenses, hoping to acquire property by default eventually.

Jesus’ final answer to the rich man is not charity but justice. The only way he can “inherit” eternal life is by restoring to its original possessors all the property he gained by fraud. Actually, the law says he must restore it plus one fifth! I think the rich man knows that, and it grieves him.

We don’t know the end of the rich man’s story. He just walks away, and Jesus doesn’t call him back with a second, less intimidating offer. But perhaps Jesus has touched his heart. It’s a good sign, after all, that he came to Jesus in the first place. He grew up accustomed to wealth and the way wealthy people think. But a new way of thinking, repentance, is possible. We can hope for his eternal salvation.

What must we, rich in America, do to inherit eternal life?

Jesus might start an answer that question as he did for the rich man: “You know the commandments.” But harder stuff is coming, some version of “sell your belongings and give to the poor.” It would not be an option, not charity, but justice. It would be Jesus’ reading of the commandments.

If we take money, land or other possessions from a poor person, we’re justice-bound to make restitution. But most of us don’t do that. Even the very rich among us aren’t literally robbers of the poor. They’re just gathering up new wealth. But there are several factors that make our day more like Jesus’ than one would like.

- When the economy is not producing new wealth, when it is actually shrinking, rich people still can get richer. That happened in a big way during the Covid recession. You could say nobody stole that money, but still money left the pockets of the poor and entered the coffers of the rich.

- No one alive today participated in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, but the wealth that slaves created then is still around, making more wealth. Most of it is in other hands than of slaves’ descendants. That’s a debt the country as a whole owes.

- Today people create new wealth. That is, all the people, from CEO’s to secretaries. Increasing productivity creates increasing wealth. A secretary’s productivity has at least doubled from the days of manual typewriters and carbon paper. The same goes for many other kinds of manual labor. But in real terms a secretary’s or a manual worker’s wage has increased very little. Since the 1980’s practically all new wealth in this economy goes to the very rich. It’s legal; but most of that wealth should have gone to most of the people who made it.

Jesus’ answer, the hard part

Could Jesus prescribe an answer to the injustice of today’s excessive and rising inequality? Jesus understood the economy of his Palestinian home, but today’s hedge funds, derivatives, and short sales would probably puzzle him. Jesus would have to rely on the opinion of experts. But which experts? Jesus’ preaching gives us a clue.

Here today, as in Palestine then, Jesus would preach against idolatry—idolatry of mammon then, idolatry of the market today. He would condemn belief in the mythical, godlike hand that turns everyone’s self-interested decisions toward a common good. He would decry the so-called virtue of greed and the magical thinking that animates a laissez-faire attitude toward extreme wealth accumulation. Jesus would rate neoliberal and libertarian economists as badly as progressive economists do.

More likely, Jesus would favor a different sort of expert. I’ve written about some of them:

- Anthony Annett, who applies Catholic social teaching to economics,

- Henry Hudson, who investigates the history of debt relief in the ancient Near East and Israel’s Scriptures,

- William T. Cavanaugh, who has written on the free market, consumerism, globalization, and Christian desire.

There are billionaires unhappy with the way wealth, including their own, accumulates. They imagine better solutions than traditional philanthropy. Marlene Engelhorn, for one, says billionaires shouldn’t have that much say. Why should the wealthy instead of representatives of all the people decide which of the world’s problems to solve and how to solve them? She wants most of her billions taxed away.

Engelhorn and dozens of others from the wealthy extreme who think like her (see this Forbes article) are examples of a proper response to Jesus’ challenge to the rich man in the Gospel story. What else might Jesus require of us today? The question requires political and economic as well as religious wisdom.