“… and they all lived happily, for a while, after.” That’s how Jesus could have ended the Parable of the Dishonest Steward. A rich man gets a bad report – just a rumor, perhaps – about one of his estate managers and fires him. The employee makes a last-ditch effort to save himself from a life on the streets. He offers his soon-to-be-former clients some substantial debt relief. The master sees how happy his debtors now are and takes a look at the newly cooked account books. He says, “What a clever fellow! He makes me look good just as I’m firing him. I might have to keep him on now.”

We find the parable in the Gospel of Luke, and Luke is the story’s first and most influential interpreter. William Herzog, another interpreter, attends to the way Jesus’ audience would have heard the story. Jesus knew his listeners. What they heard must be what Jesus meant. And that, in Herzog’s view, might be something different from what Luke makes of the story.

The Parable of the Dishonest Steward is the last parable that Herzog considers in Parables as Subversive Speech. This is my eleventh and next-to-last post on that book.

Previous posts in the series:

- William Herzog Reads Jesus’ Parables, Brings them Down to Earth

- Paulo Freire, the “Pedagogue of the Oppressed”: Is This a Good Fit for Jesus?

- Laborers in the Vineyard: A Reading that Doesn’t Blame the Victims

- The Parable of the Wicked Tenants and the Wickeder Landlord

- The Rich Man and Lazarus, or an Oppressor who Won’t be Taught

- The Unmerciful Servant Parable Trashes Messianic Hopes

- The Horrifying – or Tragic – Parable of the Talents

- Publican and Pharisee: A Parable of Two Public Sinners

- The Friend at Midnight – Shameless, but in a Good Way

- Unjust Judge Out-Shamed by Persistent Widow – a Parable

Jesus’ Parable of the Dishonest Steward (Luke 16:1-8a)

Luke gives us the parable itself and an application—all in words he attributes to Jesus. The division between parable and application occurs in the middle of verse 8. Scholars question whether the application that follows is Jesus’ own commentary or Luke’s addition. Perhaps Luke incorporated independent sayings of Jesus into a commentary on the parable.

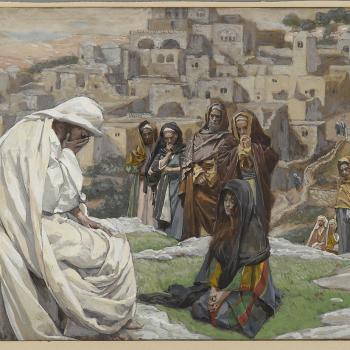

A rich man had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property. He summoned him and said, ‘What is this I hear about you? Prepare a full account of your stewardship, because you can no longer be my steward.’

The steward said to himself, ‘What shall I do, now that my master is taking the position of steward away from me? I am not strong enough to dig and I am ashamed to beg. I know what I shall do so that, when I am removed from the stewardship, they may welcome me into their homes.’

He called in his master’s debtors one by one. To the first he said, ‘How much do you owe my master?’ * He replied, ‘One hundred jugs of olive oil.’ He said to him, ‘Here is your promissory note. Sit down and quickly write one for fifty.’ Then to another he said, And you, how much do you owe?’ He replied, ‘One hundred kors of wheat.’ He said to him, ‘Here is your promissory note; write one for eighty.’

And the master commended that dishonest steward for acting prudently.

Application (Verses 8b-9)

For the children of this world are more prudent in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light. I tell you, make friends for yourselves with dishonest wealth, so that when it fails, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.

Traditional interpretations

Most interpreters of this story assume that the charges brought against the employee are true. He make no attempt to defend himself, so he must be a”dishonest steward.” Herzog challenges this assumption, as we’ll see later.

Again interpreters often consider the master to be a God figure. It would be a merciful God, like the Father of the immediately preceding Parable of the Prodigal Son and Forgiving Father. This master doesn’t punish his steward other than to dismiss him. He even accepts his loss of income; that is, he OK’s the debt forgiveness the steward engineered. He a kind, generous person, a good stand-in for God. Herzog also disagrees with this assessment.

After a brief, less than realistic sketch of the economic background of the parable, the traditional interpretation moves on to, in Herzog’s sarcastic words, “more interesting ethical and theological applications.” Given the wide and conflicting variety of applications interpreters have come up with, Herzog thinks that move lacks sufficient preparation. Some of the “lessons” various scholars have drawn from this parable are:

- the need for decisive action in the face of a crisis, particularly the approaching Day of the Lord that Jesus preached;

- the proper use of money and the value of almsgiving;

- the need for practical wisdom in spiritual affairs like the way “children of this world” handle worldly problems;

- the confident hope Christians can have in the abundant mercy of God.

All of these can find support in the parable and Luke’s follow-up commentary. All depend on taking the masters praise of the dishonest steward as if it were the words of a good and even godly figure. But given the actual relationship between rich and poor in Jesus’ world, that’s hardly the way Jesus’ audience would see the rich man.

The lifestyle of the rich: conspicuous consumption,

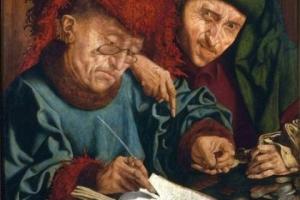

The “rich man” of the parable is very rich. You can tell that by the debts owed to him. Scholars have estimated their value. One hundred jugs of oil – eight or nine hundred gallons – was worth 1000 denarii, almost three years’ wages. One hundred “kors” of wheat, the yield of 100 acres of land, was worth seven-and-a-half years’ wages. These are only two of the debtors whom the steward calls in “one by one.”

Most of this wealth comes from expropriating the surplus production of poor farmers in lieu of rent, fees, and taxes. In this case “surplus” means anything above what is absolutely necessary for mere survival.

The story’s debtors follow the dishonest steward’s directions and rewrite their own contracts. They can write! That, in addition to the size of the contracts, indicates that these probably are not peasants. More likely, they belong to the newer class of merchants, to whom the estate owner sells his fields’ produce on credit. The merchants make their living by finding markets for the agricultural goods.

Both merchants and peasants, unlike the steward, are off the ladder of upward economic mobility and prestige. The steward, on one of the lowest rungs, is in cutthroat competition with other employees of the estate just as estate owners compete with their much richer ilk. The competition plays out in conspicuous displays of wealth – large homes, fancy imported clothing, and sumptuous meals of tenderest calf and lamb.

Pity the poor, dishonest steward

Such competition explains the master’s reaction to the bad report he receives about one steward. We don’t know who initiated the report, or rumor. It could be peasants fearing they have too little left to live on after all the expropriation. It could be merchants unhappy with the size of the steward’s cut. Or it could be other stewards, envious and desiring to bring down a too-uppity competitor. The master takes the reported behavior as a threat to his own standing and fires the steward.

It’s a death sentence for the steward. His prospect is life as a day laborer, the lowest social class. Having lived off his skills with numbers and letters and badgering others, he’s not prepared for the life that faces him. He needs a way out of his predicament.

The dishonest steward and the weapons of the weak

Society’s underclass have ways of coping with oppression other than revolt. There are “everyday forms of peasant resistance.” Like: foot dragging, deception, false compliance or passive non-compliance, evasion, pilfering, feigned ignorance, and slander.

Herzog describes the place of such “weapons of the weak”:

The master’s code treats peasants as resources to be squeezed to the limit. The steward’s code is to survive while making a profit … [lucrative] yet small enough to avoid attracting the master’s attention…. When the villagers are unhappy with the steward, they attack him anonymously through rumor, gossip, and backstabbing.… Merchants would use the same weapons.

On hearing the report, the master sides with the complaining villagers or merchants. Protesting innocence will do the steward no good, so he turns to more “weapons of the weak.” He intends to show his employer how valuable his service is.

Pretending that he has the master’s permission, he lowers his client’s bills, but not just arbitrarily. He takes out exactly that portion that would have been interest, which the Law forbids. Somewhat shadily this amount shows on the bill not as a separate figure but as an increase of the premium. This maneuver has the employer’s tacit approval, but, officially, it’s the steward’s doing and the steward’s responsibility if it ever goes to court. “This is the value of the risk I’m taking for you,” he reminds the master, without saying it.

The master gets a profit, though less than he expected. He might follow through on his decision to fire the steward, now with even greater reason. But the debtors, who still don’t know about the steward’s dismissal, are already singing the praises of the master and feeling friendly toward the steward as well. The master concludes: better to accept the loss, keep the steward, and let the debtors’ good will work to his advantage in the future.

The take-away – the parable’s good news

At the end, the parable turns upside down the usual situation of estate owner, steward, and peasants or merchants. Instead of mutual distrust and hatred, now peasants or merchants are praising the estate owner, this employer commends the steward, and the steward gave a nice gift to his clients and kept his job.

Herzog thinks that cancellation of debt, a prescription of the Scriptures and a main theme of Jesus’ preaching, is key. The estate owner, who had all the power, lost. The weapons of the weak provided

… a glimpse of a time when debts would be lowered, and a place where rejoicing could be heard. This may not be a parable of the reign of God, but it suggests how the weapons of the weak can produce results in a world dominated by the strong.

Comment on a hard verse

And I tell you, make friends for yourselves by means of dishonest wealth so that when it is gone, they may welcome you into the eternal homes. (Luke 16:9)

This verse always puzzled me, but it began to make sense when I learned from Herzog that scholars have interpreted it as encouragement to give alms. “Dishonest wealth,” or more literally the “mammon of iniquity,” is the wealth of this world. However you might have obtained it, it necessarily involves a history of injustice. Still, it has its legitimate uses, especially for almsgiving. Now imagine that the beneficiaries of your almsgiving die before you do. Of course, they’ll welcome you “into the eternal homes.”

My NRSV Bible translation refers to when the money “is gone.” The Greek word, eklipe, could have a stronger meaning. Strong’s Concordance (online) gives it additional meanings of “die out” or “come to an end.” Think: eclipsed. It’s not just that your money ran out. It’s when the time for mammon is over. That gives “eternal homes” an eschatological, end-of-the-age perspective.

Finally, another hard verse

I have decided what to do so that, when I am dismissed as manager, people may welcome me into their homes. (Luke 16:4)

Herzog ignores this line except to dismiss it. He rightly insists that peasants or merchants would never welcome the steward into their homes as a permanent, unemployed guest. That idea is what I imagined the above line implied, and I think the tradition imagined it too. But Jesus and his listeners surely would have known how ridiculous it is as a permanent solution to the steward’s problem.

So, why did Jesus say it? Notice that the line doesn’t say “permanently.” Permanence sneaks in to our reading, I think, because of the later verse, quoted above, about welcoming into “eternal homes.” But that verse isn’t part of the parable as Jesus told it. So we can pare down the meaning of “welcome.” It might only mean that the steward’s former clients now would be willing to greet him on the street, maybe have him over for tea, or at least be friendly when he calls to collect on debts.

Herzog doesn’t imagine this possibility. He thinks the history of enmity between money collectors and their clients is too strong. But I think some new neighborliness helps the Steward’s ploy to work. He doesn’t hope for or want to be a permanent guest. His only chance for survival is for his boss to give him his job back. A better standing with his clients will improve his chances for that.

On second thought, a very simple way to make sense of this puzzling line is to say that Luke, not Jesus, put in the “welcoming me into their homes” part. He might have snuck it in to go along with the later verse about welcoming into “eternal homes.” Luke added that verse, scholars say. I think the story actually reads well if you go from “I have decided what to do” directly to “So, summoning his master’s debtors….” But my qualifications for critiquing a biblical author’s editorial work don’t go that far.