In the Transfiguration scene does Mark give us a brief glimpse of Jesus’ triumph over the cross and glory in the Kingdom of Heaven? On the contrary, Ched Myers believes it’s the cross itself that comes into view here. I add my own thought about the Kingdom and its power.

Fourteenth in a series on “The Worldly Spirituality of Mark’s Gospel” with help from Ched Myers’ Binding the Strongman: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. The Introduction and a Table of Contents are HERE.

No picture in Mark’s Gospel lends itself more to putting Jesus into another world than the Transfiguration. Myers would say that is about the opposite of what Mark intends. Jesus transfigured looks a lot like a resurrected Jesus, but again Myers looks somewhere else. He says the symbolism of the Transfiguration points not to resurrection but to struggle, suffering, and martyrdom. (Myers, pages 250-56)

Mark gives us no view of the resurrected Jesus after the crucifixion, where you would most expect it. I mean the original Mark, not the endings added later as Chapter 16, verses 9-20. Given that, I think it’s likely that Myers is right, that there’s something else in view at the Transfiguration. That something is the cross, and that is what I’ll explore in this post. I’ll start with the episodes leading up to the Transfiguration.

Peter confession and Jesus’ harsh words (Mark 8:27-33)

Jesus cures a blind man with some difficulty. (See last post.) It’s a complicated symbol. It says the disciples may come to understand, but it won’t be easy. Immediately after this miracle Jesus addresses the issue of understanding directly and literally: “Who do you say that I am?” Peter declares, “You are the Messiah.”

It sounds to me like Peter actually does understand, but Jesus doesn’t approve of Peter’s declaration. Matthew (16:17) has Jesus approving effusively. In Mark Jesus doesn’t necessarily even agree with Peter. Instead he immediately refers to himself, not as Messiah but with the ambiguous title “Son of Man.” Jesus knows Peter has a taste for a triumphant messianism. He shocks Peter with the first of three predictions of his passion.

Peter, still thinking of triumph, rebukes Jesus for saying such a thing, and Jesus rebukes Peter back. Mark didn’t tell us exactly how the devil tempted Jesus in the desert, but here the temptation is clear. Peter, as the devil, tempts Jesus to steer away from the hard path ahead. Jesus has hinted about the Jewish leaders being on the devil’s side. He doesn’t hesitate to make the same accusation against his own follower. “Get behind me, Satan,” he says to Peter, not bothering to be subtle about it.

The perils of following Jesus

Jesus continues speaking, and he’s addressing the crowd openly. (Mark 8:34-38) With the miracles he commanded silence, but this isn’t about miracles: “Whoever wishes to come after me must take up his cross and follow me.” Whether you’re in Jesus’ audience or one of Mark’s first readers, this can only mean the cross of crucifixion. Mark isn’t recommending ascetic practices or stoically putting up with life’s inconveniences but the courage necessary for those who risk Roman displeasure. Members of Mark’s community may have to take up a literal cross on the way to execution.

Then comes the following saying:

“Whoever is ashamed of me and of my words in this faithless and sinful generation, the Son of Man will be ashamed of when he comes in his Father’s glory with the holy angels.”(Mark 8:38)

We can feel the cross weighing down here also. There are things in Jesus’ life and words that an inhabitant of the first-century Mediterranean world might consider shameful, but nothing so much as the cross. More than torture, the cross was the Romans’ way of publicly shaming its victims. The Jews’ own Scriptures said, “God’s curse rests on him who hangs on a tree.” (Deuteronomy 21:23) Curse, shame, unimaginable pain – all are Jesus’ lot and the risk Jesus’ disciples take.

The Kingdom of God will come “in power.” Myers’ interpretation

Jesus’ next words are puzzling:

He also said to them, “Amen, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the kingdom of God has come in power.” (Mark 9:1)

On the face of it, it seems simply wrong. The kingdom of God hasn’t come even today with anything like what looks like power. At the time of Mark’s writing, 40 years after these words, Jesus’ timetable was running out. Most, though not all, of the people “standing here” must have died already.

Myers says to consider the ones the Son of Man “will be ashamed of” in the previous quote. They are of a “faithless and sinful generation.” That is the same generation that Jesus said earlier would get no powerful sign from heaven. (Mark 8:12) Myers thinks that, for Mark, there is a sign but not something “this generation” will recognize, not a heavenly sign. The kingdom comes with the “event of the cross,” and “that is what ‘some of those standing here’ will live to see.” (Myers, page 248)

Another thought about the Kingdom’s power

Perhaps Myers is too fixated on the cross here. It doesn’t make much sense for Jesus to say “some of those standing here” will live for another week or so. But Myers is right to rule out the prediction of some heavenly spectacle, since there is that earlier refusal of a sign to “this generation.” (Actually, at the Crucifixion scene Mark does give two apparent signs. Darkness covers the land from noon to three, and the sanctuary veil is torn in two. (Mark 15: 35 and 38) If Mark is being literal, these would contradict Jesus’ assertion that no sign would be given. I think Mark must have meant them as symbols, and the symbolic meaning is easy enough to read.)

I don’t think Jesus is predicting here either a Parousia coming soon or a powerful display at his own crucifixion. But “some of those standing here” undoubtedly did live to see Mark’s own day and community. The Kingdom’s coming in power could be the quiet but fearless kingdom living in a Christian community, one that risks the literal cross of Roman retaliation for practices that contradict the normal ways of that Mediterranean world.

This would be a sign of power, though an earthly one. It would be a sign that Rome and other “powers that be” would have trouble recognizing as a sign at all. They would have reason to fear it, though. Mark’s Gospel soon will turn to a series of teachings by Jesus that will give a clearer idea about the subversive nature of the kingdom that is coming.

The Transfiguration

Before that teaching there is the trip up and down the mountain of Transfiguration. It occurs “after six days.” I wonder about this number. Surely it’s not a historical detail. Who is going to remember exactly how many days went by between two events 40 years previously? In telling and retelling surely that detail would fall out, if it were ever there. I’m guessing that Mark here engages in number symbolism, as he often does. Six is the number that symbolizes imperfection or incompleteness. I imagine Mark telling us that the disciples, in this case Peter, James, and John, are not ready for what’s coming.

The symbols in Mark’s telling are: mountain, Moses and Elijah conversing with Jesus, and white clothes. We have what appears to be glory shining right out of heaven. But Myers says think again.

In the Exodus story Moses also climbed a mountain. He could look down from that mountain and what did he see? The Israelites were worshiping a golden calf. (Exodus 33) Elijah climbs a mountain in flight from authorities who seek his life. There he meets Yahweh but only in a “tiny, whispering sound.” I used to think that the tiny sound must have been scarily powerful. But a more straightforward reading is simply that it’s just tiny—not the power that one might hope for from God. Elijah and is then sent back down the mountain to continue his dangerous mission. (1 Kings 19:11ff) These are moments of struggle, not of glory.

On Easter and at a Baptism we associate white clothes with resurrection, but the white of Jesus’ clothes speaks to Myers of martyrdom. In Revelation (7:14) the ones in white robes are those “who have survived the time of great distress.” They have “washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.” All of these symbols—the mountain, Moses and Elijah, the dazzling white—portend something very different from triumph and glory.

Peter is oblivious to this symbolism. He’s beside himself and suggests a tent-building project to honor the three august figures. A voice from heaven shuts Peter down and ends the vision: “LISTEN TO HIM.” Listen to what Jesus has been trying to get across all along.

On not spiritualizing the cross

On the way down the mountain Jesus counsels silence as he has before. This time it’s about a vision that has been misinterpreted. He makes another effort at wiping away faulty ideas of triumph and replacing them with the cross. The three disciples ask about the common belief that Elijah is supposed to come again. Jesus answers, “Elijah [he means John the Baptist] has come and “they did to him whatever they pleased, as it is written of him.” Similarly, Jesus continues, it is written “regarding the Son of Man that he must suffer greatly and be treated with contempt.” (9:12-13)

Not being well-acquainted with crosses, we can easily spiritualize what Jesus says about taking ours up. Then our cross turns out to be the sacrifices we make and the sufferings that are part of life. But that has very little to do with power. This modern, privatizing interpretation of the cross could not have been that of the first readers of Mark’s book. When they took up the cross, as Mark intends them to, it was public, political, and powerful enough. If it didn’t end in crucifixion, that was always the risk.

No shortage of crosses today

I don’t mean to say anything against ascetic practices or thinking that in bearing life’s sorrows we share Jesus’ cross. Elsewhere Jesus speaks of that cross, for example, “Blessed are you poor.” (Luke 6:20) But it’s not the cross that Jesus is speaking of here. I would connect this cross to the person who takes the dangerous path of living and speaking for justice:

- To the person who objects when in a friendly conversation someone uses an unconscious ethnic slur, like “Jew me down.” I did that.

- To the person who turns away when someone offers a “white man’s price.” Regretfully I didn’t do that.

- To the person who gave her life in a demonstration against white supremacism.

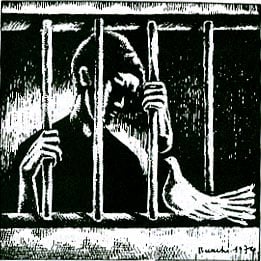

- To the person in jail for non-violent civil disobedience in a just cause.

- To Dom Helder Camara, who said, “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.” Likewise to St. Oscar Romero, martyred for upholding the rights of the poor.

Today there is no shortage of dangerous crosses of the sort that Jesus means when he says:

Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and that of the gospel will save it. (Mark 8:34-35)

Image credit: Community in Mission, Archdiocese of Washington