Love, InshAllah is proud to feature occasional author interview podcasts. This episode features Deonna Kelli Sayed interviewing Bushra Rehman about her Poets and Writers featured novel, Corona.

Love, InshAllah is proud to feature occasional author interview podcasts. This episode features Deonna Kelli Sayed interviewing Bushra Rehman about her Poets and Writers featured novel, Corona.

Deonna Kelli Sayed (DS): Here at Love, Inshallah, we are proud to focus on powerful personal stories from Muslim women and men, and sometimes, writers of other faiths, on love, marriage, family and life, in general. The 2011 call for Love, InshAllah book submissions asked for something simple yet transformative: American-Muslim women writing on something many people do not associate with the Muslim experience – love and relationships.

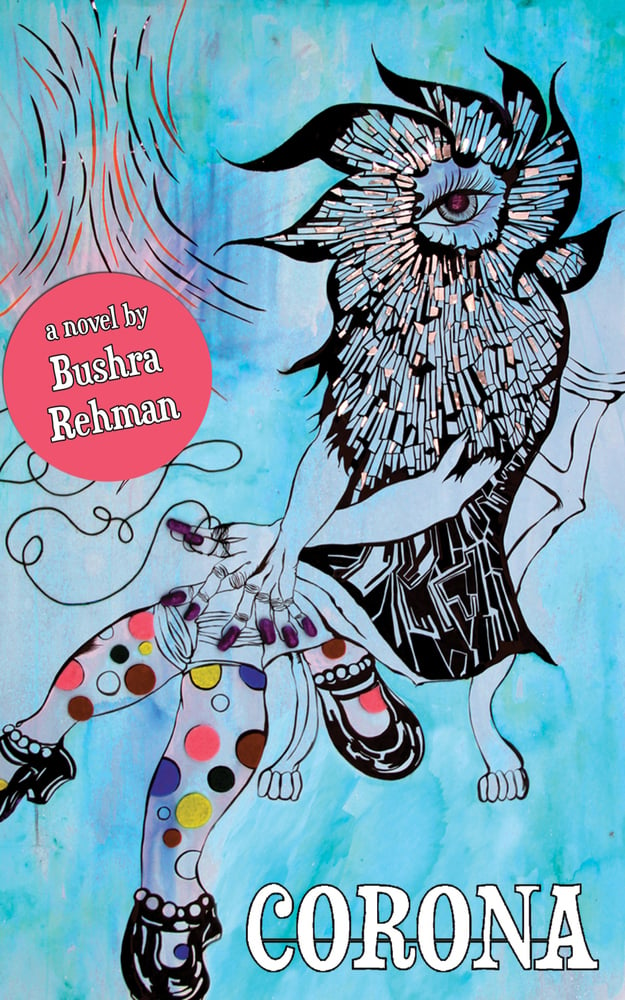

New York City-based poet, Bushra Rehman, found the idea of writing about love intriguing. Love, InshAllah inspired one chapter from her debut novel, Corona, a collection of stories about love, loss and transcultured identity, a book she says is:

Bushra Rehman (BR): Corona is a dark comedy about being South Asian in the United States. It is a poetic, on-the-road adventure novel starring Razia Mirza, a Pakistani girl from Queens, who gets disowned by her family, and who ends up taking a Greyhound bus and having adventures all over the country.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/106221014″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

DKS: Corona — not the beer but the place in Queens – focuses on a character like Bushra who grew up first generation Pakistani-American. Razia is a character we don’t often see in the emerging genre of contemporary Muslim fiction: she isn’t necessarily a victim, nor is she interested in becoming part of mainstream white America. She is sometimes a confused, yet brave South Asian-American woman carving out new cultural space despite numerous challenges.

Corona deals with several issues facing people like Razia – transcultured identities, individuals operating between multiple cultural norms, often represented by family expectations on one end and stereotypes on the other.

BR: When I was writing the book, I was writing in some deliberation in that I wanted to create character that I hadn’t seen before, and I wanted to write the kind of stories that I think are funny and interesting. Those stories were about a character that was confident, bold, risk-taking, a little bit vulnerable and wild. Someone who doesn’t always make the best decisions, but has a lot of fun even when she isn’t making the best decisions.

DKS: One key theme in the book is Razia’s parents disowning her and how she creates a life beyond that and, eventually, reunites with her family while trying to remain authentic to her own calling. And for this reason, Bushra says:

BR: I hope everyone reads Corona, except my family! For those who haven’t read the book, there are drugs, sex, all kinds of adventures. Things that we were not raised to do; things that I wasn’t raised to do. Some of us are so tight with our families, we don’t want to hurt them, we don’t want to get disowned. But Razia is disowned early in the book, so this happens to her.

People will get out of it [the novel] what they want to get out of it, but it would be cool for people to see that her life doesn’t end when she is disowned. She goes on and she has these different adventures. Eventually she makes up with her family.

The way the novel is structured, those scenes are not always present. The disownment scene isn’t present, but it is the negative space from which the whole novel rotates. It is the heart of it.

I would like girls to see that life doesn’t end when you are disowned. In my community, that was the thing always held over our heads if we did anything wrong. That was the punishment for the crime.

DKS: While Razia’s life choices may be extreme, she does struggle with the same issues impacting many first-generation children: balancing several different masks one has to wear — sometimes one in front of your family, another outside of the home. But this is one aspect of contemporary global identities — that there is no “one” self.

BR: I don’t think these things are particular to just Muslims. We all live multiple lives in one life. When I write, these choices are not deliberate.

I studied psychology for a while, and there is this idea that we are supposed to have a one unified personality. But there are other psychologists that say we all have different personas. It is just how we move in the world and that is healthy, as well. Razia it is a little extreme because she has so many different adventures in life and she is so much of a chameleon, but I think that is one of the things that is charming about her.

You know, at one point she is living with a family where the guys are extremely macho, misogynistic, homophobic, and she is writing all of this stuff that is the opposite of that. But then every night, they just hang out. So it shows when we pick our friends, our friends aren’t necessary in the same political party and there is something really beautiful about that.

DKS: Now, let’s get to a love story. In Corona, Razia has many different types of romantic relationships. One that transformed her in unexpected ways was her experience with Ravi. I asked Bushra to talk about this.

BR: So Razia hasn’t dated a lot of Desi, aka South Asian men, suddenly finds herself madly in love with this Bengali man who is only in the country for a little while. And they go to Bangra Blow Out, this bangra dance competition, and they end up sleeping at a friend’s house. He does not know that she likes him, and this is that moment when they come back to the friend’s house to go to sleep:

Ravi zippered up his sleeping bag, and I curled into mine. A few minutes later, he was snoring softly, but I couldn’t sleep. It wasn’t lost on me that Ravi was a present day version of what my father and uncles had been. They had paved the way, knocking their heads against the concrete of New York City, working in stores, factories, and low-level labs. They made room for the likes of Ravi so his kind could come like big spoiled children and leave the same.

Ravi let out a snort. I turned. His mouth was slightly open and his face dark in the light filtering in from the window. If I had followed the way set out for me by my family, I would have been going to bed with a man who wore salwar kameez every night. Maybe I had made some bad choices in my life. But it was ridiculous to think this way. I could only be the person I had been born to become.

You know, when I wrote that line, “I can only be the person I had been born to become,” I think that line surprised me. As someone who lives what many consider to be an alternative lifestyle, that line comforted me, and I hope it comforts other people, too.

DKS: Bushra comes back to this idea that when Muslim women write, it seems that regardless of faith or cultural identity, we are not always empowered to fully, freely reveal. Many of our stories aren’t accepted as authentic unless we are use a “victimization” or “oppressed” platform. I asked Bushra to talk about this:

BR: Coming back around to the those narratives, maybe “victim narrative” isn’t the right phrase. Maybe a “healing narrative.” When we use the word victim, that is a label that is put on someone who may be speaking out the truth. I like the word survivor better, but that is a heavy word.

I hope that Corona is found by those teenagers who are struggling, especially young girls struggling with a similar community that I grew up in. I want people to see that life goes on.

DKS: Life does go on, indeed, and during the summer of 2013, Bushra gave birth to her first child, a daughter. I asked how becoming a mother might impact her writing:

BR: I am so happy that I had a choice when and with whom I wanted to have a child. I thought a lot about how it would impact my writing before I made this choice. I realized that so many of the writers I loved were mothers. For example, could Toni Morrison have writing Beloved had she not been a mother? I am even reading that book differently now that I am a mother. I do feel an increased sense of urgency to support myself with my writing so I can be with her more and not have to work a million jobs.

I do hope she reads this book one day and is proud of me and enjoys it.

I was reading an interview with Ani Difranco. She is a mother now and she was asked this question. She said that it interrupts her writing. You know, as Rosina is only seven weeks old right, it is the point of interruptions. But I am such a workaholic, this is actually a weird place for me to be in, just sitting and holding a baby. I can imagine that this will definitely influence my writing, but I don’t yet know what that will be.

Sometimes having that interruption – that dreaming space, that nothing space – can be really helpful for a writer.

DKS: I ask Bushra what advice she has for young women; Muslim, South Asian, or women of color, who want to write:

BR: To call ourselves Muslims is also radical. I think that is another reason our stories aren’t all there. We can’t take the name on if we are doing things we aren’t supposed to do.

I do think that is one reason there is less of us — Muslim American female writers — because we have that fear, that fear is so deep, that keeps us from writing, publicizing and sharing our work. We have to get to the heart of that fear. It is the voices in our head that tells us that we shouldn’t be talking about these things.

But it is your life, your story, and you own it. People act as if they have more ownership over your life story than you do.

DKS: Corona, the novel, is out August 2013 and is published by Sibling Rivalry Press. To learn more about Bushra, visit her website. Thank you for listening. This is Deonna Kelli Sayed for www.patheos.com/blogs/loveinshallah.

—

Bushra Rehman is a writer and poet. She is a co-editor of Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism (Seal Press, 2002). Bushra’s poetry has been collected in the chapbook Marianna’s Beauty Salon (Vagabond Press, 2001). Her writing been featured on BBC Radio 4, WNYC, KPFA and in The New York Times, India Currents and NY Newsday. Her work has also appeared in ColorLines, Crab Orchard Review, Mizna, Curve, Sepia Mutiny, The Feminist Wire and SAMAR. Bushra’s work has been anthologized in: Indivisible: Contemporary South Asian American Poetry (University of Arkansas Press), Collective Brightness: LGBTIQ Poets on Faith, Religion and Spirituality (Sibling Rivalry Press), Ladies and Gents: Public Toilets and Gender (Temple University Press), , Stories of Illness and Healing: Women Write Their Bodies (Kent State University Press) and Voices of Resistance: Muslim Women on War, Faith and Sexuality (Seal Press).