Love, Inshallah Author Interview: Melody Moezzi, Haldol to Hyacinths: A Bipolar Life

Narrated and produced by Deonna Kelli Sayed

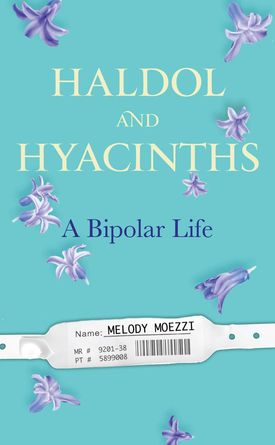

DKS: In the 2011 anthology, Love, Inshallah: The Secret Love Lives of American Muslim Women, Melody Moezzi wrote about her struggle with chronic physical illness and how her husband provided love, support, and compassion. Melody’s latest book-length work, Haldol to Hyacinths: A Bipolar Life, is a deeply personal, often humorous memoir that explores her journey with Bipolar 1 Disorder and how faith, cultural identity, and love illuminates her recovery.

A lawyer, award-wining author and an activist, Melody’s identity as an Iranian-American-Muslim woman becomes a metaphor for her struggle to understand her illness, one she shares with approximately 4.4% of American society.

I asked her to explain how a highly educated, lucky-in-love, Iranian-American woman decides to reveal a deeply personal story about a misunderstood and often stigmatized diagnosis.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/109118103″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

MM: I realized when I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, I realized there was a stigma associated with this that wasn’t with any other of the minority categories I belonged to. I thought as a Muslim-Iranian-American woman, I had seen the brunt of what discrimination and prejudice looked like. But I hadn’t, compared to the way that I was treated in the hospital and the way that I saw other people treated – and the silence surrounding it.

Suddenly, there was this new minority I suddenly belonged to, and I was ashamed of it, for the first time in my life. And I was raised to be proud of where I come from. To suddenly be told to be quiet about it by the same people who raised me to be proud of being Iranian and American and Muslim and everything about myself – that was really shocking

DKS: After years of mania and depression, Melody was successfully diagnosed in 2008 and subsequently, found access to the right treatment plan and medication. Bipolar 1 disorder can be wrought with hallucinations, delusions, extremes highs or lows in mood, and impulsivity. In her case, such impulses lead to a suicide attempt, a story she first shared in 2010 on CNN.com.

Her activism became deeply personal after years of improper diagnoses, medications, and humiliating, dehumanizing inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations. She realized that she had profound personal power in telling her story — but there was a process in accepting her diagnosis.

MM: I didn’t want to go down that path. As an activist, I didn’t want to put myself out there like that necessarily. I wanted to do it in a way that, “Oh it is not necessary to share my story.” But the things I relate to are human stories, and the things that I write are human stories. I think I needed to get my story out for myself.

Mainly, I wanted to encourage other people to be able to do the same thing because I feel the more we are willing to tell our stories as people living with mental illness, the more other people are willing to do that. There is something really liberating about telling your story.

DKS: She certainly doesn’t fit the highly inaccurate stereotype of someone with mental illness. She isn’t disabled or violent or contagious. Melody is an attorney with a Masters degree in Public Health. She is an award-winning author who has made many national and international media appearances. Many people who suffer from mental illnesses are highly educated, high functioning individuals.

Yet, in a society where an Iranian heritage and a foreign name already makes one suspect, surely there are social, professional and personal risks with publicly revealing that you are a mentally ill Muslim?

MM: Initially with the book I was talking to my agent when I first pitched the book and I said, “just basically tell them it is an Iranian-American Muslim bipolar feminist memoir,” because that niche, you know, it is a whole genre that hasn’t been filled.

When you try to relate your story to other people, and I had tried that for a while, and I was leaving parts out of myself because it would be easier for other people to understand. All that stuff that is part of me, I was leaving out in, conveniently, in certain essays and things, but I couldn’t leave it out in this because there was no way I could write a memoir without addressing being an Iranian-American. That is an integral part of me. If someone asks me to tell them about myself, one of the first things I would say is that I am an Iranian-American.

DKS: As an activist, she is quick to point out that mental illnesses are real issues facing millions of Americans, and others worldwide, on a daily basis. In the US, mental health funds are shrinking, and there is an increased urgency to demonstrate the impact of budget cuts and the daily struggles of such illnesses in relevant, human currency.

MM: I’m not sure how many people realize how many people in this country live with a mental illness. It is like 60 million people – 25% of adults in this country – if all of those people were to stand up, imagine what we could accomplish.

Right now, [in North Carolina], we aren’t fighting to get more funding. We are fighting so we don’t get cuts.

No one is going to be able to fight these fights unless there are human faces and human stories attached to them

DKS: Melody’s story is so important because she is a minority, transcultured woman from a faith-based community. There are unique considerations when one falls into these specific demographics, particularly when dealing with communities that have different cultural perspectives on mental health.

MM: I think for a lot of the faith communities, there is the idea that you can pray your way out of this. I think it has a lot to do with education.

I found within the Muslim communities with the diaspora who are more educated, I’ve found more understanding of the medical nature, the biological nature, of the illness, which is helpful.

But there is a step beyond that, beyond just realizing it is a brain disease that needs to be treated. Even though there may be medical understanding, there remains a need for community and institutional base support.

I think with Muslims, we can address it in the diaspora through science. And take it one step beyond that – beyond “this is a real illness, “ to compassion.

DKS: These aren’t just “Western” illnesses. New research indicates that mental health and substance abuse illnesses are the leading cause of nonfatal illness worldwide, with a global disease burden that trumps that of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, diabetes, or transport injuries,” according to a recent article at Medscape.com.

Many societies, including some Muslim majority countries, are plagued with war, political instability and therefore, experience trauma, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorders.

MM: I get emails from all over the Middle East. Emails from all over the place with people telling me, “Oh, I want to know about this from a Muslim perspective. I’ve never heard a Muslim say that, ‘”I have a mental illness.’”

Really, you’ve never heard another Muslim say that they have a mental illness? But in other countries, it is something that isn’t dealt with which is unfortunate, because 4 out of 10 leading causes of disability are mental illnesses.

So it is not just a rich country problem. It is something that affects all of us. And the reason that it is so disabling is because people can’t admit that they have it is in the first place.

DKS: Here at Love, Inshallah, we can’t have an author interview without talking about love and relationships. In Haldol to Hyacinths, Melody shares about her husband, the love of her life, as a saving grace and a gift that has kept her alive.

MM: It is not an opinion. It is a fact. I wouldn’t be alive without him, for sure.

I’ve never had heartbreak. I don’t think I could take it. I really don’t. He was my first serious boyfriend. I’ve never slept with anybody else. I’ve never been with anybody else seriously. And it is funny because my friends were like, “Are you sure? You haven’t dated around!” I’m like, “No! He is perfect!” He is the smartest person I know, and I’ve met a lot of smart people. And he is hands down, the smartest person I know. He is awesome. Really stable. I don’t know if that is a necessity for someone who has a mental illness, but I think it helps.

I told him after I was diagnosed that he didn’t sign up for this and I wouldn’t hold it against him if he wanted a divorce. And he was just upset with me and said, “I knew you were crazy from the beginning!” He made me realize that my identity didn’t change who I was.

DKS: Having a partner that can help you focus on your full self is a blessing, indeed.

MM: A lot of ways, when you are labeled with something like manic depression or schizophrenia. That label carries so much weight and you take it on as part of your identity in a way that can be really harmful. And he helped me not do that.

It was definitely a gift from God and the best gift one could feasibly get in life, I think.

[Music]

DKS: It took a lot of bravery, and humor, for Melody to share her story. She is quick to point out the importance of speaking, writing, and living authentically.

MM: I’ve always been open about being an Iranian-American and Muslim. That is something I’ve never tried to hide, and that is part of the reason I felt I had to write the book.

Look at what you are most afraid of look at what scares you the most in life and yourself and go there. That is where the gold is. That is where good writing comes from, good art comes from; it comes from taking a risk.

One of the advantages of bipolar is that I tend to be more impulsive when manic, and I’ve done some impulsive things that have turned out really well.

I might not be a writer today. It was hard to graduate law school and get a Masters in public health. I had all these options open to me and to say, “Well I want to be a writer!” You know, that wasn’t easy.

DKS: And even in struggles, there are unexpected blessings.

MM: Something with bipolar is that a lot of delusions – and you hinted at it – have to do with religion. A lot of them have to do with politics. I thought I was a prophet when I was manic.

These delusions, for sure, are very dangerous. It is not all useless. It is not all throwaway. There is something that I can experience, that people with mental illness can experience, that isn’t so much illness, but that is insight.

I think that it is important to acknowledge that this is a medical illness that needs to be treated. But there is value in the insights because of the fact that you can go higher on the spectrum of joy and lower on the spectrum of misery.

[Music]

As an activist, when people try to shut you up, it is because you have something important to say.

So when you ask, “why did you write the book?” the more people tried to shut me up, the more I realized that it was important to keep talking.

DKS: Haldol to Hyacinths: A Bipolar Life (Avery, August 2013). To learn more about Melody Moezzi, visit her website at melodymoezzi.com. This is Deonna Kelli Sayed. Thank you for listening to an author interview podcast for www.patheos.com/blogs/loveinshallah

—-

Music used in this podcast complies with open source, free use, and/or non-commercial licenses:

- Falken: “Learning to Forget”

- Atom Wrath: “Intro”

And the following selections from WIRED CD. Rip. Sample. Mash. Share

- Zap Mama: “Whadidyusay?”

- Matmos: “Action at a Distance”

- David Byrne: “My Fair Lady”