“What are you watching?

This question from my father, as innocent as it seems, makes me lovingly cringe.

“It’s a show Dad.”

“Is it a movie?” he’ll say, sitting next to me on the sofa and squinting at the TV. More internal cringing.

“No Dad, it’s a show.”

“What’s it called?”

Here’s where things get tricky, because A) some of the more nerdy shows I watch have weird names and B) my dad, as a rule, will always mishear the title. I can mumble or enunciate, it doesn’t matter. I call this Dad’s Third Law of Hilarious Misinterpretation.

“Doctor What?” he’ll ask quizzically.

Or,

“Firebug? Fire kya?”

Or,

“Battle Galacticus?”

There is a lot of affectionate eye-rolling and gritted teeth and repeating myself until he gets it right. Once the title is established, he’ll try watching for a few minutes. He asks questions, tries to follow along. But inevitably, after a max of 8 minutes (sometimes 10 if there are commercials), he’ll shake his head and say “this is weird. You watch weird shows,” before retreating behind his newspaper. I call this Dad’s Second Law of Attention Span.

God bless him, he does try.

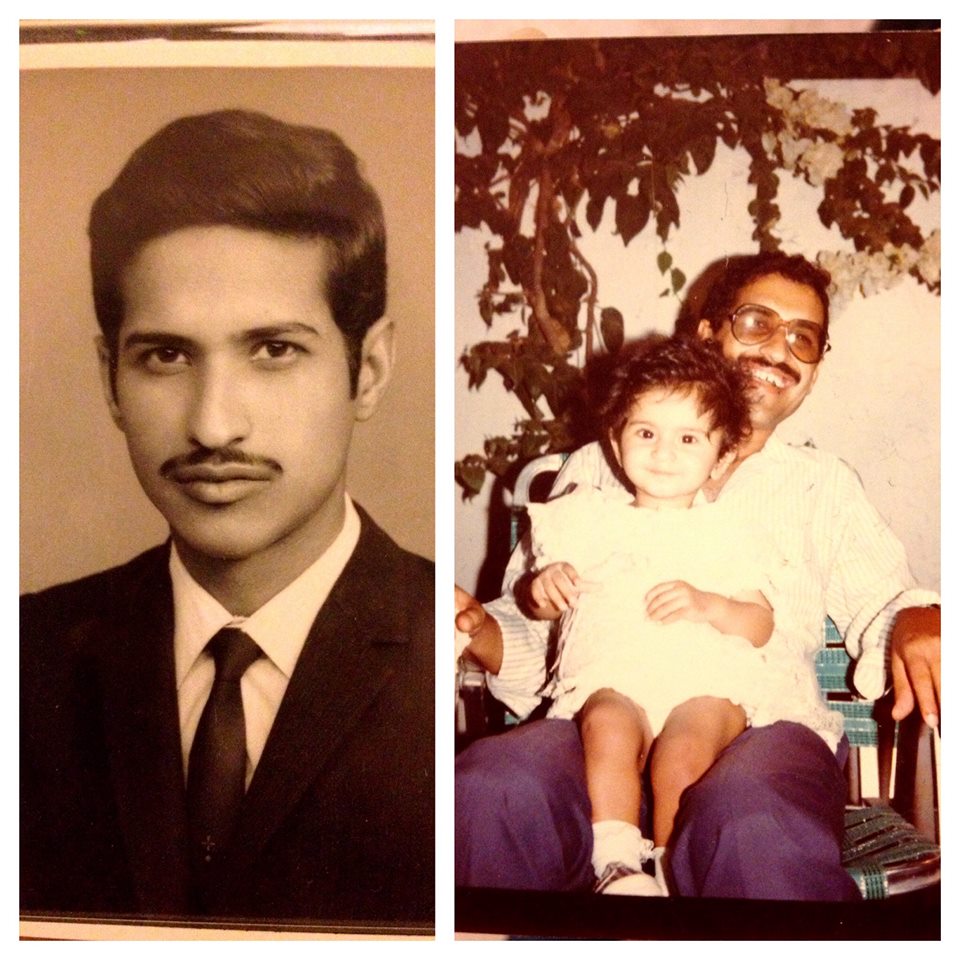

So much of who I am today is because of my father. In his day, he was often given the highest praise of intellect that existed in Pakistan: he was told he had the brains and the focus to be a doctor. He chose instead to blaze a trail according to what interested him, and become an engineer with a concentration in computer science (“There’s no future in computers,” my grandfather told him back then). Stories from his childhood consist of both brilliance (first in his class throughout school, save for one year – 3rd grade – when he “may have slacked off a bit”) and mischievous adventurousness (the time he rode his bike past school and home to take a ride – alone – in an airplane, a novelty in that era; he was 8 years old and no one knew where he’d been since he was home in time for dinner).

My father has always been decisive, marrying a healthy mix of the pragmatic with the idealistic. He traveled the world while serving in the Pakistani Navy, picked up smatterings of various languages along the way, and has never been afraid of getting lost in a foreign country.

When I was younger, my mother would note with motherly dismay, that I tended to look like my father: all bony appendages, sharp angles, boyish short hair, a gap-toothed smile, and eyes that disappeared entirely when I laughed. My dad and I got our kicks out of exasperating her every time she tried to take a picture. We would smile until our eyes were slits, and when she protested, we’d open them extra wide to look like manic patients freshly escaped from a psych ward.

Older now, and a tad more feminine, I look like an exact copy of my mom. But my personality, my interests, my desire to explore without a map and speak every language, my insatiable curiosity for the world, and my inherent mix of pragmatism and idealism come mostly from my dad.

As adults, we reach a level of clarity when it comes to our parents. We understand what they left behind and the sacrifices and hardships they faced in life. It is enough to make your heart swell, even as your heart aches for their younger selves.

My father made a decision thirty-one years ago to leave behind his familiar world, friends, family, and home, to give his baby daughter better opportunities and a chance at a brilliant education. Here, he was able to raise me as he always wanted – in his words, “both as a son and a daughter.” I am his eldest and his toughest child. We’ve built furniture together, tinkered with electronics, sated our mutual curiosity for the world in the gold-tipped pages of the Encyclopedia Britannica my parents bought me before I could even read, explored foreign countries through our National Geographic subscription, and debated international politics at the dinner table. Over the years, my dad has encouraged my independence and my opinions, even when those opinions clashed with his. For all of this, I cannot be grateful enough.

Perhaps it is the luxury of second generation children of immigrants to imagine brave new worlds and explore science fiction models. We have made our homes in one place without uprooting our lives. Perhaps for us, the next leap will be migration to Mars or colonies on the moon. But we’ve been given the tools of survival-through-adaptation by our forbearers.

My dad can be forgiven for not understanding alien worlds: in his lifetime, he’s traversed continents and concepts that were alien enough. For that, he remains my very first superhero.

—-

Zainab Chaudary works in politics by day and as a writer by night. Her blog, The Memorist, ruminates upon travel, religion, science, relationships, and the past, present, and future experiences that make up a life. She tweets @TheMemorist

Zainab Chaudary works in politics by day and as a writer by night. Her blog, The Memorist, ruminates upon travel, religion, science, relationships, and the past, present, and future experiences that make up a life. She tweets @TheMemorist