Our new book, Salaam, Love: American Muslim Men on Love, Sex & Intimacy, will be released on February 4th. In the lead up to the release, meet our 22 contributors.

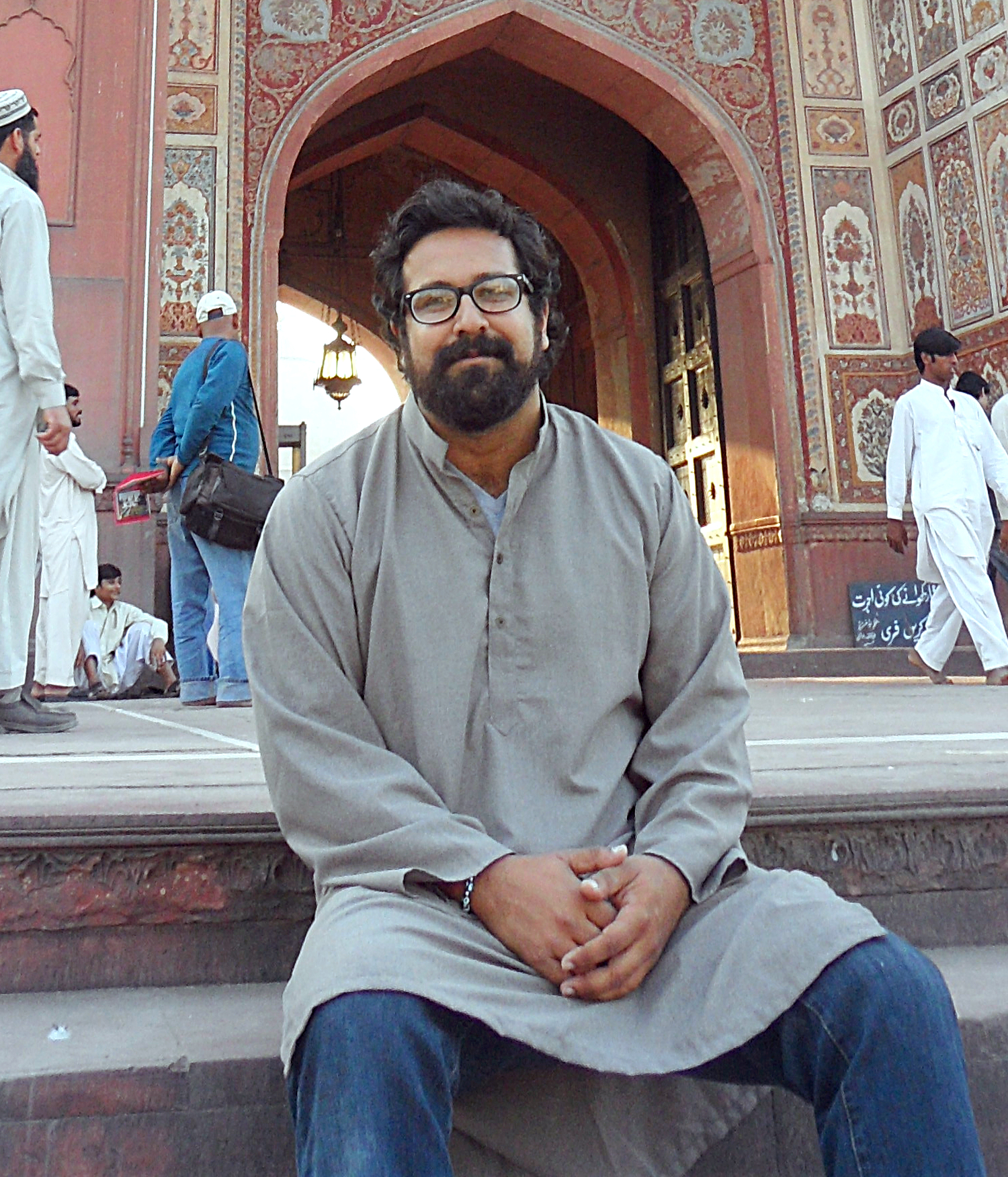

Today, meet Alykhan Boolani!

An excerpt from Alykhan’s story, “A Grown Ass Man”:

“Sorry—what did you ask, Chacha?”

How old are you now?—no longer a question, but an annoyed test of patience.

It was inevitable. I already knew whatever number I said would precipitate the dangerous mantra my uncle was dead set on delineating. At twenty-nine, this question is a predetermined, existential adjudication: the contextual set of evidence being that my older cousins (all twenty-six of them) are exempt from this line of questioning; that my sister is well on her way toward respectable, Isma’ili family-hood; and that here in the old country, my tawdry theories of progressive neocultural hybridization make even less sense than usual. I make eye contact with no one, grab a little Karachi banana from the center spread of postdinner fruits, and brace for the worst.

“You’re overdue,” he says.

Like rent. Like car payments. Like this banana covered in soft, brown spots.

To read more, order Salaam, Love today!

Q&A with Alykhan

Tell us about yourself

I’m a Pakistani-American who more readily identifies as a person of color. I like tents because they are small and efficient, and they sate the feeling of unboundedness I find myself craving more and more. I spend a lot of time attempting to translate books to grade-level that are too advanced and ethereal and post-modern for my eleven year old students. I like to think about Socrates and Buddha and Karl Jaspers and Jesus writing pen-pal letters with Muhammad. I’m way too romantic for my own tastes. I’ve never written anything that has been shared with others before.

Why were you drawn to this project?

I was drawn to this project because I took a year off of work, and I was in Pakistan when I heard about it, digesting all the horrors of a city called Karachi, a place my mother once referred to as “serene.” Being a Muslim these days is a funny business, and so when the story came to mind–silly, irreverent, romantic–it came rushing, solipsistically, in my own way, as a indirect response to my ineptitude for gravity in grave times.

What was the most challenging part of sharing your story?

Thinking about what my mother would say. She is blindly faithful, and deeply embroiled–socially, politically, economically–in our community. In putting our relatively small, insular community on blast–certainly a shanda fur die goyim–I felt like I was speaking words that had been, until now, spoken in the private language of family.

Then, of course, there was the tact involved in telling the woman I went on a failed date with that I had created a story chronicling our cosmic downfall for public consumption.

If there’s one thing you hope that readers will take away from your story, what is it?

I can only hope that my brothers and sisters who feel me on this can read my story and laugh a hearty, familiar laugh. That would be a small, good thing.

Anything else you want to share?

I am eternally reverent of the power of stories, and the strength and hope that follows in writing and sharing them. Thanks for creating space for self-possession, a moment to own our voices, especially in the current political stratosphere, where “our” voice tends to be the imaginary, hyper-patriarchal voices of demonized others.