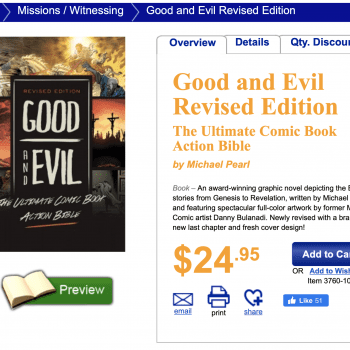

The word “spanking” is used in so many different ways. Some use it to mean slapping a toddler’s bottom or thigh for misbehavior in the moment, others use it to mean sending a child to their room for a paddling, and some use it to encompass essentially any physical violence. My parents practiced a sort of “ritualized spanking” a la Michael Pearl and James Dobson. Despite my parents’ best intentions—and their care in following the rules laid out by these teachers—my experience was profoundly negative.

I wrote this post a while back and have held back from posting it, because it is painful. But my story has a lesson to offer. Many parents who simply want the best for their children are drawn in by the teachings of various parenting experts who teach that spanking can be appropriate and healthy if it is not done in anger, if the transgression is explained, and if parents show affection afterwards. But my parents followed all of these rules perfectly, and yet it was neither appropriate nor healthy. I want to share my experience in hopes that some parents will read and be dissuaded from the promises that if spanking is ritualized it will not be not harmful.

I was primarily spanked by my mother. When she announced that I was to be spanked, she would send me to the bathroom to await my punishment. I would sit on the closed toilet seat, the bathroom door closed, and wait. And that waiting was terrible. I knew I was going to experience both serious humiliation and serious physical pain, and that there was nothing I could do to stop it. Sometimes I would think about a story in the Book of Virtues, about a young man with the ball of string, where if he pulled the string he would skip forward through his life. How I wished I could have a ball like that, so I could pull the string just a little bit and have it over with.

Then my mother would enter the bathroom and close the door behind her. She would retrieve the paddle from the bathroom drawer where it lived. She would go over my transgression to make sure I knew why I was being punished. Sometimes she would have it slightly wrong, and I would try to explain what had actually happened. But that was not allowed. Attempts to explain myself earned me additional spanks. My mother had a spank tally, usually starting with three, and would add more for further attempts to explain. I would feel stifled, ignored, not listened to. I would feel like I was going to explode, everything bottled up inside me, my mouth pressed shut.

Sometimes my mother actually had a basic fact of what had happened wrong, and even when she didn’t, what would it have hurt to listen to my explanation? Why penalize any attempt to explain what I was thinking when I did XY or Z as though that were an additional transgression in and of itself? I’m a mother myself now, and I consider listening to my children—even when they’re simply trying to justify something they did wrong—to be incredibly important. It’s about building a mutual relationship where we are free to be open with each other, where we listen to each other in turn. I want my daughter Sally to know that I value her words and her perspectives—even when her justifications can’t explain away whatever it was that happened. And regardless, there is a learning opportunity here—one that is missed when communication is stifled or punished.

Sometimes I asked my mother for an alternative punishment. I assured her that I understood that a punishment was necessary, but I begged her to please—please—let it be something else. I found being spanked so humiliating and degrading that I would readily take essentially any other punishment. I would offer to write sentences, or have a long timeout, or give up one of my possessions for a time. I would beg her to please—please—not spank me. Sometimes I would even cry as I begged. But my mother believed in “consistency,” and by that she meant that once she said she would do something she could not change her mind. This is a problem, as it locks people into carrying out an action even if they determine in the process that it is not the best action.

Sometimes I asked my mother for an alternative punishment. I assured her that I understood that a punishment was necessary, but I begged her to please—please—let it be something else. I found being spanked so humiliating and degrading that I would readily take essentially any other punishment. I would offer to write sentences, or have a long timeout, or give up one of my possessions for a time. I would beg her to please—please—not spank me. Sometimes I would even cry as I begged. But my mother believed in “consistency,” and by that she meant that once she said she would do something she could not change her mind. This is a problem, as it locks people into carrying out an action even if they determine in the process that it is not the best action.

Once I finally accepted the futility of attempting to explain or ask for an alternative punishment, I would say the words I was required to say—the apology my mother wanted to hear. Sometimes this apology was a lie, whether because my mother had the facts wrong and so I had to lie as though she had them right, or because I still did not believe that I had actually done wrong. And what is the point of an apology that is a lie? What does this teach a child, to put them in a situation where they will say anything—even lie—because physical pain is staring them in the face? How is this that different from cases where a tortured prisoner will say whatever he has to to make the pain stop?

After the apology, I would have to lean over the toilet and prepare for her blows. If I moved while my mother was spanking me—if I tried to get away or block the blows—she would add spanks to the total tally. Instead of the original three, I might have six, nine, or even twelve. If she finished spanking me and felt that my body language was still “rebellious,” she would keep going. A stiff body, a stony face—those things were signs I hadn’t truly learned my lesson. I had to act broken—repentant, she would say. I learned to fake the body language of brokenness, and I learned to fake it well. Sometimes I would be crying at the end of a spanking. If my crying was deemed too loud, I would be told to “cry quietly,” and if I didn’t acquiesce—if I wailed or cried loudly—I would be spanked again, for being “rebellious.” Once again, I learned quickly to do whatever I had to do to avoid more pain. But inside, I would bleed.

Then my mother would tell me she loved me, and give me a hug. This hug was required. Refusing to let her hug me or refusing to hug back was a sign that I was still “rebellious” and had not learned my lesson. That could lead to another spanking. Sometimes I did want the hug, but other times all I wanted was to get away from my mother. She had just ignored me and hurt me, and what I really wanted was to go somewhere and hide until I felt better. Being forced to hug my mother even though with every ounce of my being all I wanted to do was get away from her and run was yet one more humiliation on top of the rest. Inside I would be choking, gagging.

Now some might say that while traumatic, at least my parents’ system was effective—right? I mean, I’m not perfect but I’m not in jail, I can hold down a job, and by all appearances I’ve successfully made the shift to adulthood. The thing is, I don’t think my parents’ system of “ritualized spanking” was necessary to get me here. I was a very logical child, and also a child who very much wanted to please others and do the right thing. Discussing my actions with me and using other punishments when needed—a loss of privileges, say—would have been both more effective and less traumatic. After all, I cannot remember, to this day, any of the things I was spanked for. What I remember is the humiliation and shame of being spanked, not whatever lessons she was trying to teach me.

I would have preferred to have more of a mentor/mentee relationship with my parents. Instead, our relationship was closer to that of a police officer and an ordinary citizen—assuming, of course, that the police officer was also the one making the rules. When I got in trouble, I would be punished, and there was little effort put into discussing what had happened or why. There was little effort put into me learning anything beyond “don’t do that.” And there was very little attention paid to why I’d done what I’d done, what I’d been thinking, and what my motivations were. The result was a system that was inflexible and devoid of nuance—a system built more on rules and punishment than on growing and learning.

My parents use of “ritualized spanking” also set up an oppositional parent/child relationship. But it doesn’t have to be that way. I am of the opinion that parenting should be cooperative, and that children should be involved and listened to. If a parent believes, after speaking with the child about their actions, that a transgression deserving of punishment has been committed, what is so wrong with letting the child help decide what their punishment will be? And while I’m not saying motivations are the only thing that matters, they do matter. If a girl fails to set the table because she is helping her younger brother with some difficult schoolwork, shouldn’t that matter? I would argue that people matter more than rules, and that learning something from a situation is more important than is ensuring that a transgression is punished.

Maybe, just maybe, other parents can learn something from my reflections on my childhood experiences. I think that sometimes parents who had childhoods where punishment was carried out in anger or where the rules were inconsistent are taken in by those teaching this sort of “ritualized spanking”—where punishment is not done in anger and where the transgression is explained and affection is shown. They are promised that if they follow these specific steps, all will be will, and their children will turn out both well behaved and well adjusted and happy. I’d like to give these parents pause. And perhaps, for some, I have.