The Friendly Atheist recently shared a spreadsheet of secular candidates, most of them at the state level. I’m often skeptical of such lists, given the reality that secular individuals, like anyone else, can be misogynists and white supremacists. Indeed, “incel” terrorists tend to be nonreligious. Still, this list seems pretty solid—these are individuals with solid progressive credentials. And, I noticed almost immediately, a lot of them are women. 56 out of the 141 state legislature candidates listed, to be precise.

This started me wondering—just how many women are running for office? I’ve heard that rather than a “blue wave,” we should be talking about a “pink wave.” But what does that look like exactly? Vox reports on this “pink wave” as follows:

Women are running for office in record numbers this year. Most of those running are Democrats. While women comprise 43 percent of Democratic candidates in 2018 congressional general elections, they make up only 22 percent of Republican Senate candidates and only 13 percent of Republican House candidates. While Democratic women won House primaries at rates 20 percentage points higher than Democratic men, Republican women and men won House primaries at similar rates.

Vox explained this difference as follows:

Democratic elites are motivated to political action by candidate gender; Republican elites are not. Specifically, among Democrats, even mainstream party donors often support candidates due to gender-related concerns, while even Republican donors who donated to women’s PACs infrequently reference gender as a primary motivation.

In other words, Vox argues that Democrats donate and vote for women because they are women, thus giving Democratic women an advantage over Democratic men, but Republicans do not, treating each male and female candidates the same. I think there is a piece missing from Vox’s analysis, however. I don’t think Republicans actually treat male and female candidates the same.

The Vox article links to a relevant study that came out this summer, but does not fully analyze the study’s implications. Here is the study’s abstract:

The conventional wisdom in the literature on women candidates holds that “when women run, they win as often as men.” This has led to a strong focus in the literature on the barriers to entry for women candidates and significant evidence that these barriers hinder representation. Yet, a growing body of research suggests that some disadvantages persist for Republican women even after they choose to run for office. In this paper, I investigate the aggregate consequences of these disadvantages for general election outcomes. Using a regression discontinuity design, I show that Republican women who win close House primaries lose at higher rates in the general election than Republican men. This nomination effect holds throughout the 1990s despite a surge in Republican voting starting in 1994. I find no such effect for Democratic women and provide evidence that a gap in elite support explains part of the cross-party difference.

Vox addresses this study here:

…while 59 percent of Democratic Party donors indicated gender issues are a very important component of donation decisions, only 16 percent of Republican women’s PAC donors said the same. While 80 percent of Democratic donors to women’s PACs noted a gender-related organization among the groups that helped them decide on candidates to support, only 46 percent of Republican women’s PAC donors did.

This distinction helps explain why Republican women are disadvantaged in fundraising compared to similar Republican men, while Democratic women in some cases raise more than their male counterparts.

But if the Republican Party were actually treating men and women the same, why would Republican women face a fundraising disadvantage in comparison with Republican men? Vox indicates that Democratic donors trust the recommendations of women’s PACs while Republican donors do not—but whether or not donors listen to women’s PACs only explains why Republican women do not have a gender-based advantage, not why they appear to face a gender-based disadvantage.

It appears that while Democrats are predisposed to support female candidates, Republicans are predisposed to support male candidates. I’m over treating disproportionate support for male candidates as some sort of general neutral and disproportionate support for female candidates as something odd.

This isn’t about one party preferring female candidates and the other having no preference. It’s about one party preferring female candidates and the other preferring male candidates.

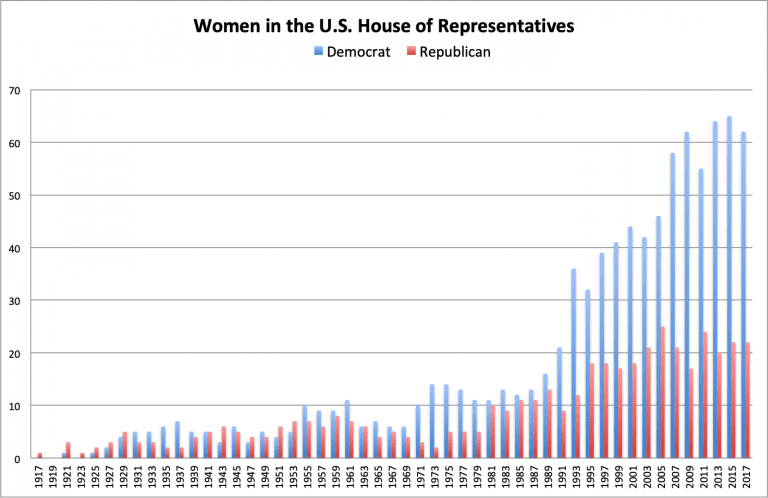

I’ll leave you with this fascinating chart:

Fascinating, right? Republicans and Democrats elected relatively equal numbers of women candidates through the 1960s. In the 1970s, there was a sudden uptick in the number of Democratic women in the House while the number of Republican women actually declined slightly—until the 1980s, that is, when the number Republican women in the house jumped to meet the number of Democratic women.

Until the 1990s, that is. I grew up in the 1990s, and I’m becoming increasingly convinced that everything bad in this world has its origins in the 1990s. (I’m only partly kidding.) In the 1990s, the number of Democratic women in the house jumped by a lot while the number of Republican women grew slightly but stayed mostly stable. That pattern has continued to the present day.

It’s perhaps worth noting that the number of women in the House has yet to top 20%, even with the higher Democratic numbers seen above.

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!