Door in the Dragon’s Throat, pp. 7-12

I’ve enjoyed reviewing Stepping Heavenward over the past few months—the historical aspects especially—but I’ll admit there some aspects of the Christian fiction I’ve reviewed in the past that I’ve missed. Over the holidays, I found Frank Peretti’s Cooper Kids Adventure Series at a used bookstore. I read this full series as a young teen, and absolutely loved them, so I picked one up and started perusing it. Me oh my. I knew immediately that I had to review it.

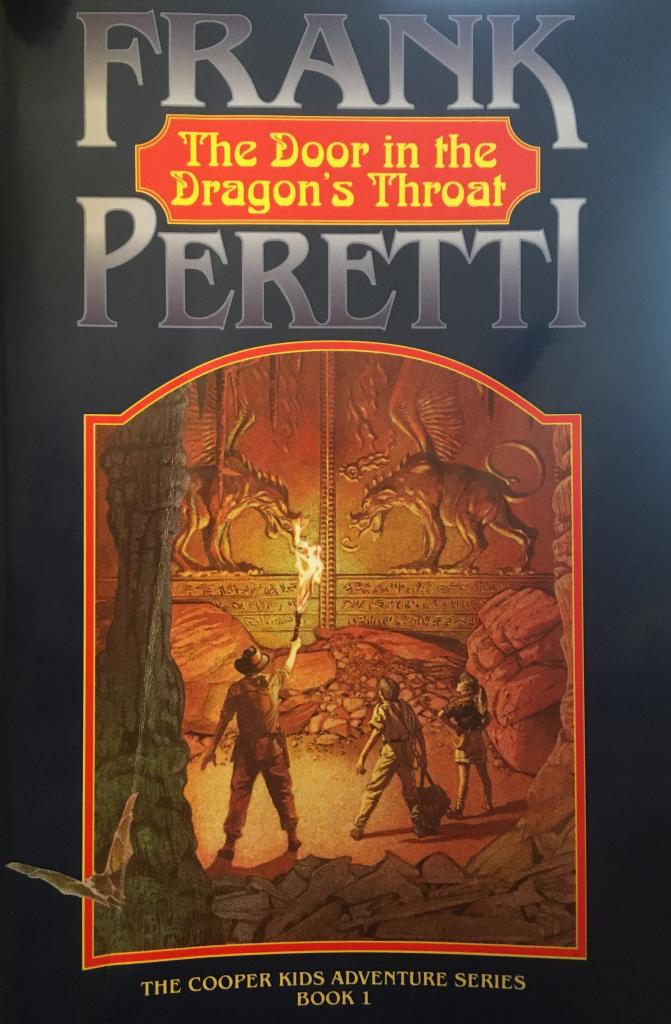

So we’re going to pause Stepping Heavenward for a bit—we will come back to it eventually, or maybe in bits and pieces—and take a dive into Door in the Dragon’s Throat, the first book in Frank Peretti’s adventure series for teens.

Here is how the book opens:

In the arid and strife-torn Middle East, land of Bible adventures, wars, camels and kings, in the tiny, secluded, landlocked nation of Nepur, a nation known for its strange customs and ancient mysteries, pompous President Al-Dallam, Chief Magistrate and Bearer of the Royal Scepter, starts and fidgeted at the huge marble desk in the presidential palace.

Oh. Boy.

In case anyone is wondering, this book was published in 1985.

There are so many stereotypes ands so much negative imagery in this one paragraph that it could be used as a textbook example of orientalism.

An incredibly wealthy oil sheik, President Al-Dallam always wore a long, diamond d-studded, purple robe, gold rings on his fingers, and a very impressive silk turban on his head.

What the heck is a “very impressive” silk turban? What exactly is it about this turban that makes it “very impressive”?

He loved being his country’s president, he loved being rich, he loved being powerful.

Now this is just bad writing. Whatever happened to “show, don’t tell”?

Right now, his huge desk was piled high with important papers and business of state that needed his official attention, but he couldn’t concentrate on any of those things.

Important papers? What exactly makes them important? I get the feeling this book is going to lean really, really heavily on a complete reversal of “show, don’t tell.”

This is a “tell, don’t show” kind of book.

His mind was too flooded with thoughts of becoming even richer.

Are you effing serious??

An excited knock on the big double doors to his office interrupted his daydreams, and a voice called excitedly, “Mr. President! My liege!”

Al-Dallam had been waiting all morning to hear that rough, raspy voice. “Gozan! Come in! Come in!”

The big doors burst open and in came Gozan, a bearded, rugged desert rat of a man.

What?! No! There is no bottom to this.

Al-Dallam imagined a small cloud of dust escorting his assistant into the office; Gozan always seemed to have a “common man” air about him. Gozan removed his big straw hat and made a hurried oops-I-almost-forgot bow.

Gozan, Al-Dallam’s assistant, has come to announce that the Americans have arrived—Dr. Cooper’s expedition. When Al-Dallam asks how many men Dr. Cooper brought, Gozan “started counting his fingers as he watched faces in his mind.” It takes him a few minutes to volunteer that Dr. Cooper brought his children and three workers. Gozan is Al-Dallam’s assistant, but he apparently struggles to count to five.

“Children?” The president was obviously unhappy, and that always made Gozan feel a little edgy.

For his time, Frank Paretti was an extremely high profile evangelical author. For a while in the 1990s, you’d have been hard pressed to find an evangelical Christian who hadn’t read This Present Darkness, or some other Frank Paretti demon fighting flick. But let’s call this portrayal what it is—racist. And not just a little racist. A lot racist.

Al-Dallam is upset. He’s really upset. He’s upset that Cooper has brought his children with him. “Children will only get in the way,” he declared. “I warned him of the great dangers.” Gozan is also unhappy that Cooper brought his children, but explains that “apparently they are very well trained and can take care of themselves.”

I find this whole section a bit weird. I don’t think anyone would have cared all that much that Cooper brought his children (except perhaps to ask whether entertainments should be arranged for them—perhaps they’d like to see the sights). Al-Dallam does also express disappointment that Cooper didn’t bring more men—only three–but it seems to me that this ought to be the focus of his concern, as it’s most relevant to Cooper being able to do the task he’s arrived to do. Instead, Al-Dallam’s focus is on how totally and completely inappropriate it is that Cooper brought his children.

This is a book written for teens. I suspect that Paretti is trying to build Jay and Lila up as characters—those are Dr. Cooper’s children—by starting with a lack of belief in their skills or their relevance, thus making their success when they prove themselves indispensable all the greater. It positions them as underdogs.

“Gozan, this is no task for children! It will take an army, not just four men and two … children!” Al-Dallam only shook his perplexed head. “They will all be killed the first day. The Dragon’s Throat has no mercy!”

Gozan bowed again, and stayed bowed for a few moments. He knew that what he was about to say could be risky. “Mr. President, many have tried, and no one has succeeded.”

It seems there’s been a German expedition with forty men, a team from France, a team from the United Nations, and a Swiss expedition, and no one has succeeded. Al-Dallam has sent letters all over the world, but there is no one left willing to attempt what he’s asking. This strikes me as unrealistic.

So many works of fiction of this sort don’t feel like they take place in the world we live in at all. A world with a supernatural door in the desert that has every archeological team in the world shaking in their boots would be a very different world from the world we live in.

“May my liege live forever, but why did you invite a mere scientist from America and his two young children? What made you think they could succeed where all the others have failed?”

The president spoke in a lowered voice. “I have heard reports about them. I have been told they are fearlesss. They are a peculiar kind of Christian.”

He did not just say that.

Gozan snuffed through his nose and said, “Christians! Of what value is that? Others have claimed to be Christians…”

The president’s eyebrows arched upward, crinkling his forehead. “Yes, but these people are different. They hold a very deep belief in their God, ssh much so that they derive some kind of special power from this deity. I don’t understand their kind of religion, but they do not have the same fears as we do.”

Lord no.

I can’t say how much this reminds me of the fictional stories I used to write in high school. There was one where an ordinary teenager is shipwrecked on an island off the coast of New England—an island not on any map. He is taken in by the people who live there, people who have fled the secular, humanistic society of the United States to live out their religion and beliefs in peace and seclusion. Every family on that island was like my family, except perfect—they were all large homeschooling families where the girls dressed modestly; the children were obedient and had long lists of chores they did without complaining; and the older children contentedly cared for their younger siblings.

In my book, this shipwrecked teen—I think I named him Justin—was constantly amazed by how kind, how happy, how content the people he encountered were. He was blown away by them, and ultimately decided to join them, to become one of them. This is what I imagined—that everyone around me could see how perfect and desirable my family’s way of life was. That everyone around us was impressed and amazed by us. That we stood out, that we were special, that people would automatically see and want what we had.

Peretti is doing the same thing with evangelical Christianity. He imagines that even the president of a nation halfway around the world away sees and understands the specialness of evangelical Christians living in the U.S. But just like in my stories, this is not based in fact. If my story had been realistic, that shipwrecked teenage boy would have been horrified by what he saw—by the expectation of absolute obedience, by the strict dress code, and so much more.

I wanted to believe that my way of life had some sort of magical power that would be evident to outsiders. Peretti appears to be channelling this same desire.

Still, Gozan isn’t convinced by Al-Dallam’s explanation. “They’ve never tried to enter the Dragon’s Throat,” he says. “They will learn to fear.”

“But they must open the Door!” the president shouted in a sudden burst of anger. “Anything so impregnable, so fortified, so guarded by curses must contain incredible riches! I must have that treasure!”

So that’s our plot—the money-hungry president of an imaginary nation in the Middle East wants a mysterious door in the desert opened because he believes it leads to a vault full of treasure. Everyone who has attempted to open the door so far has failed, often with much death, but our “pompous” leader thinks Dr. Cooper’s team may obtain a different result, because they’re evangelical Christians, and that makes them special.

So that’s cool.

The scene ends with Al-Dallam telling Gozan to meet the Americans and take them to the door. Gozan objects—he has never gone into the “Dragon’s Throat,” the passageway that leads to the door, and he doesn’t want to. Al-Dallam leaves him no choice—it’s an icky scene—and tells Gozan to bring back an eyewitness description of what happens when the Americans reach the door.

And that is where I’ll leave you this week. Exciting!

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!