Nonetheless, Tom decided to join the Jesuits while he was at Georgetown, but he waited until after attending Yale Law School and working as an attorney in St. Louis for two years. In May 1878, he told his parents that he was entering the Jesuit novitiate in England. His mother was overjoyed, but his father wavered between denial and outrage. Having experienced lifelong financial troubles, he expected Tom to be the future support of the family. Father Joseph T. Durkin, a Jesuit historian, writes that General Sherman never fully forgave his son. He felt that Tom was shirking his family obligations. Tom tried to explain the situation to his sister Minnie:

People in love do strange things… Having a vocation is like being in love, only more so, as there is no love so absorbing, so deep and so lasting as that of the creature for the creator. What a grand thing it is always to be as it were shooting straight at one’s mark, living every hour, performing every action in direct preparation for the great hereafter.

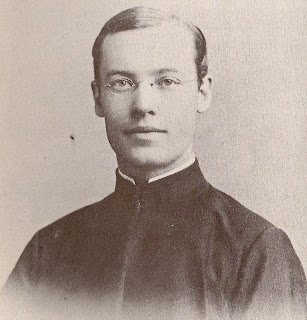

Tom Sherman spent the next eleven years preparing for the priesthood. After completing his novitiate, where his position “quite corresponds to that of the cadet in the army,” he returned to America for further studies at the Jesuits’ Woodstock College, founded in Maryland in 1869. For three years he taught at St. Louis University, but teaching didn’t appeal to him as much as public speaking did. Still he had an influence on his students, several of whom followed him into the Jesuits. Even in the order, Tom Sherman was a man set apart. In 1889, he wasn’t ordained with the rest of his class, but in a special ceremony by the Archbishop of Philadelphia (at his mother’s request).

After ordination, most Jesuits take up teaching or parish work. But Father Sherman seems to have written his own ticket, becoming a popular public speaker and Catholic apologist. Father Durkin writes: “He had a flair for the dramatic and an acute sense of theatre.” He further adds: “There is no doubt that the reflected fame of his father contributed to his power of bringing out the crowds.” A contemporary described Sherman as “always hungry for a parlor.” He could be opinionated. He once told a lady at a dinner party: “You should be a Catholic. You are too intelligent not to be a Catholic.”

As time went by, Sherman came into conflict more frequently with his religious superiors. Father Durkin describes him as “a high-strung individualist of an extreme refinement of nature and a disposition unusually sensitive.” Sherman’s superiors felt his fame was going to his head, and ordered him to stop lectures for a while. He responded by writing to Rome directly for a leave of absence from the order and got one. Afterward he procured a chaplain’s commission during the Spanish-American War, without seeking the permission of his superiors.

In 1911, after several years of drifting from one assignment to another, Sherman had a nervous breakdown and was sent to an insane asylum. When he left the asylum he traveled around the country from one Jesuit community to another. Nobody knew what to do with him. “Having served in six provinces,” he wrote, “I am attached to none.” In a fit of despair, he said: “I am utterly at a loss what to do… no peace is possible for me.” In the fall of 1914, Tom wrote a formal declaration of his severance from the Jesuits.

For the next ten years he wandered around the country as an unattached priest before settling in Santa Barbara. Father Durkin writes that he “was allergic to the mention of the word Jesuit.” Before his death, however, he did reconcile with the Society and renewed his vows. General Sherman’s son died a Jesuit and was buried in the community’s cemetery at Grand Couteau, Louisiana. Next to him was buried Father John Salter, the grandnephew of Alexander Stephens, the Confederacy’s Vice-President.