St. Vincent De Paul (1576-1660)

Today the two largest Catholic universities in the United States are St. John’s, founded in Brooklyn in 1870, and DePaul, founded in Chicago in 1898. The two schools between them have nearly fifty thousand students. Their alumni include judges and lawyers, politicians and public servants, clergy and educators. In their commitment to service and the public good, they operate in the spirit of the religious community that founded both schools, the Vincentian Fathers and Brothers, officially titled the Congregation of the Mission.

DePaul University, Chicago (1898)

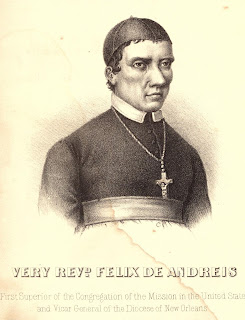

Since Father Felix DeAndreis led the first group from Italy in 1815, Vincentians have founded seven colleges and universities here. The irony is that these had no part in the original plan. When St. Vincent DePaul (1576-1660) founded the community in France, it was to meet two of the day’s pressing needs, serving the poor and training priests. It was the latter work which brought them to America. As Father DeAndreis wrote, the goal was “to found a seminary as soon as possible.”

Venerable Felix DeAndreis, C.M. (1778-1820)

In 1818, they founded their first seminary in Perryville, Missouri, St. Mary’s of the Barrens. Others followed, but a growing Church had many other needs, and within the context of their commitment to service, Vincentians took new jobs they hadn’t planned on, like running parishes and schools. Several served in bishops’ roles. When thirty-year-old Leo De Neckere was appointed to New Orleans in 1829, he was America’s youngest bishop (a record he still holds).

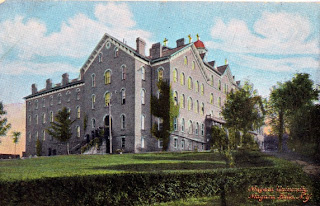

When the Vincentians undertook a college, they tended to see it as an adjunct to their seminary work. Some, notes Father Stafford Poole, didn’t consider them “a true apostolate of the congregation.” In 1842, New York’s Bishop John Hughes gave them St. Joseph’s Seminary at Fordham, also the site of a new college (now Fordham University). But they withdrew when seminarians were required to teach in the college. Father John Timon, who became Bishop of Buffalo in 1847, admitted, “I am afraid of colleges.” (But he conquered his fear to purchase land in 1856 for Our Lady of the Angels Seminary and College, now Niagara University.)

Niagara University, Lewiston, New York (1856)

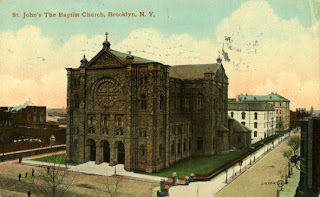

Nevertheless, they answered yes to bishops who wanted a college in their diocese. In the 1860’s, as Catholic numbers grew, Brooklyn Bishop John Loughlin asked them to found a school offering the children of immigrants “a solid education… where their minds might receive the moral training necessary to maintain the credit of Catholicity.” The College of St. John the Baptist opened in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant section on September 4, 1870. Today with central offices in Queens, St. John’s University hosts five campuses worldwide.

St. John’s University, Jamaica, New York (1870). The college is seen here in the early twentieth century, in the shadow of St. John the Baptist Church, in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant section.

In 1954, the Vincentian constitutions were revised to include non-seminary education as an official community apostolate. In a larger sense, though, such work has always been in tune with the Vincentian spirit. St. Vincent once said that the single major theme he preached through sixty years of priesthood was the love of God, which he found most closely in the face of God’s least. Father Anthony Dosen, a professor at DePaul, writes that a Vincentian education seeks to do the following:

o To educate the poor and their children.o To educate first generation college students.o To utilize Catholic teaching as a basis for its activity, especially social teaching.o To instill in students a love for the poor that leads to action.o To research the causes of poverty and seek ways to end it.

Father Dosen nicely sums up the Vincentian charism as “the integration of the love of God and neighbor.” In a recent lecture, Father Thomas McKenna, a theologian at Niagara University, said:

A follower of St. Vincent de Paul seeks to educate, first because humans are worth educating. Perhaps better put, because education has a unique and un-paralleled ability to call forth what is precisely human in people. Education is one of the prime catalysts to elicit the human, coax it out, wake it up, and massage it into life. It nourishes the human almost like nothing else can. So, if we believe in the God-based dignity of people, of course we would look kindly on the chance to grow that dignity by educating it.

Today the Vincentian approach to education is more relevant than ever. In a world that too often negates the person’s innate dignity, St. Vincent calls men and women to work for change in society, a change rooted less in a vague philanthropy than in a concrete, joyful experience of the Lord’s deep love, a love impelling us to translate it into action, to bring the Good News to God’s least, and to realize God’s Kingdom more fully, both today and tomorrow.