in which he had acted as a minister of the Protestant Episcopal Church for more than thirty years, a bishop of the same for more than twenty, and sought late in life admission as a layman into the Holy Catholic Church, with no prospect before him, but simply peace of conscience and the salvation of his soul.

His conversion was international news. The New York Times wrote: “A change of faith, on the part of a person occupying a place so prominent in the religious world, is a serious matter, independently of the merits of creed or conviction.” A Dublin newspaper commented: “As Dr. Ives is married, unfortunately there is no prospect of his devoting his energies as a priest to the service of the church of his adoption.”

“The Ives family,” writes one historian, “is one of the oldest in America.” Arriving in America in 1635, they settled in Connecticut. In the 1790’s, Levi’s parents moved to New York. During the War of 1812, he interrupted his schooling to serve as a teenage soldier. Afterward he studied for the Presbyterian ministry. But he soon decided to join the Episcopal Church, for which he was ordained in 1823. Over the next few years he served in New York and Pennsylvania.

In 1822 Ives had married Rebecca Hobart, whose father was the Episcopal Bishop of New York and founder of Hobart College. John Henry Hobart has been described as “the very embodiment of American Epsicopalianism.” Rebecca’s godmother was future saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, “whom Dr. Hobart had so strenuously tried some years before to prevent from entering the Catholic Church.”

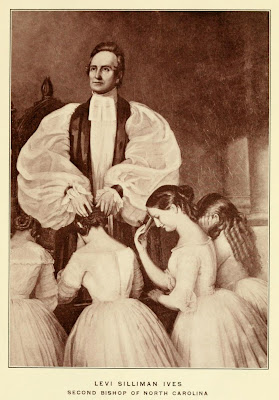

In May 1831, a Diocesan Convention held at Raleigh elected Ives Bishop of the Diocese of North Carolina. He proved an active leader who promoted education as well as an outreach to African-Americans (while supporting slavery). In 1834, he was awarded an honorary degree by the University of North Carolina.

At this time in England, the Oxford Movement was attempting to revitalize the Anglican Church by reaffirming its prophetic role. It raised eyebrows, however, when several of its adherents converted to Roman Catholicism. John Henry Newman’s decision to leave the Church of England was a shocker on both sides of the Atlantic. In America, many Episcopal clergy began to question the validity of Roman claims; one of them was the Bishop of North Carolina.

A historian of North Carolina Episcopalianism writes: “It was in 1848-’49 that the religious practices of Bishop Ives began to be at variance with the Church in which he held office.” A major concern was a religious community he founded, the “Brotherhood of the Holy Cross,” which many considered too Roman with its habit and “prayers to the Virgin Mary and the Saints.” Ives was arraigned before a church convention, but was cleared after he dissolved the brotherhood.

Nonetheless, the bishop was moving Romeward. As he read more about Catholicism, he became increasingly uneasy about his own position. Finally, in late 1852, he took the leap, traveling to Rome. In October 1853, a General Convention of the Episcopal Church formally deposed him (even though he had already resigned) for

abandoning that portion of the flock of Christ committed to his oversight, and binding himself under anathema to the anti-Christian doctrines and practices imposed by the Council of Trent upon all the Churches of the Roman Obedience.

One Episcopal historian suggests that Ives’ “mind had been affected by the long attack of fever from which he had suffered.”

For an Episcopal bishop to become a Catholic layman was no small step. There was the question of how he would support himself and his wife (who also converted). The American Catholic bishops felt a sense of responsibility for Ives, and they gathered a collection for him. One historian notes that they even discussed ordaining him a deacon and sending him to North Carolina as a sort of vicar to oversee Catholic life, but nothing came of this.

Ives moved to New York, where Archbishop John Hughes appointed him to the faculty of St. Joseph’s Seminary in the Bronx (on the present-day Fordham University campus). His home on 138th Street in Harlem became a meeting place for converts. Ives also taught at Manhattan College and the College of Mount St. Vincent.

It was in charity work, however, that he found his real niche as a Catholic. He headed the local chapter of the St. Vincent De Paul Society, a lay organization created to help the poor. In 1863, he founded the Society for the Protection of Destitute Catholic Children, which opened the New York Catholic Protectory to care for homeless orphans. Its object was

To extend to these little sufferers a helping hand, to raise them from their state of degradation and misery and to place them in a condition where they may have a fair chance to work out for themselves a better destiny.

Soon the Manhattan facilities were overcrowded, and in 1865 a 114-acre farm was purchased in Westchester.

Ives died at his home on October 13, 1867. His last words were “Oh, how good God has been to me!” Bishops nationwide attended his funeral Mass. One Catholic paper declared: “His name should ever be held in benediction as the true friend of the poor and the suffering.” He was buried on the grounds of the Westchester protectory. An Episcopal historian commented: “His was a strange and eventful life, devoted throughout to the service of God and humanity.”