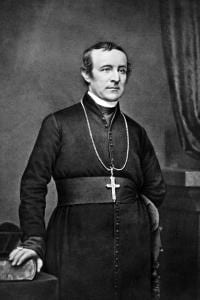

Cardinal James Gibbons’ Sermon at the Funeral Mass of General Philip Sheridan, August 11, 1888, St. Matthew’s Cathedral, Washington, D.C. (The New York Times, August 12, 1888)

Cardinal James Gibbons’ Sermon at the Funeral Mass of General Philip Sheridan, August 11, 1888, St. Matthew’s Cathedral, Washington, D.C. (The New York Times, August 12, 1888)

Well might the children of Israel bewail their great Captain who led them so often to battle and to victory. And well may this Nation grieve for the loss of this might chieftan whose mortal remains now lie before us. In every city and town and village of the country from the Atlantic to the Pacific his named is uttered with sorrow and his great deeds recorded with admiration. There is one consoling feature that distinguishes the obsequies of our illustrious hero from those of the great Hebrew leader. He was buried in the midst of war, amid the clashing of arms and surrounded by the armed hosts of the enemy; our Captain, thank God, is buried amid profound peace, while we are enjoying the blessings of domestic tranquility and are in friendship with all the world. The death of Gen. Sheridan will be lamented not only by the North but also by the South. I know the Southern people, I know their chivalry, I know their magnanimity, their warm and affectionate nature, and I am sure that the sons of the Southland, especially those who fought in the late war, will join in the national lamentation and will lay a garland of mourning on the bier of the great General. They recognize the fact that the Nation’s General is dead and that his death is the Nation’s loss. And this universal sympathy coming from all sections of the country, irrespective of party lines, is easily accounted for when we consider that under an overruling Providence, the war in which Gen. Sheridan took such a conspicuous part has resulted in increased blessings to every State of our common country.

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,Rough hew them how we will.

And this is true of nations as well as of individuals. What constitutes the difference between the wars of antiquity and our recent war? The war of the olden time was followed by subjugation and bondage. In the train of our great struggle came reconciliation and freedom. Alexander the Great waded through the blood of his fellow-man. By the sword he conquered and by the sword he kept the vanquished in bondage. Scarcely was he cold in death when his vassals shook off the yoke and his empire was dismembered into fragments. The effect of the late war has been to weld together the Nation more closely into one cohesive body; it has removed once for all, slavery, the great apple of discord; it has broken down the wall of separation which divided section from section and exhibits us more strikingly as one Nation, one family with the same aims and the same aspirations. The humanity exhibited in our late struggle, contrasted with the cruelties exercised toward the vanquished of former time, is an eloquent tribute to the blessings of Christian civilization.

In surveying the life of Gen. Sheridan it seems to me that these were the prominent features and the salient points in his character: Undaunted heroism, combined with gentleness of disposition; strong as a lion in war, gentle as a child in peace; bold, daring, fearless, undaunted, unhesitating, his courage rising with the danger ever fertile in resources, ever prompt in execution, his rapid movements never impelled by a blind impulse, but ever prompted by a calculating mind. I have neither the time nor the ability to dwell upon his military career from the time he left West Point to the close of the war. Let me select one incident, which reveals his quickness of conception and readiness of execution. I refer to his famous ride in the Valley of Virginia. As he is advancing along the road he sees his routed army rushing pell mell toward him. Quick as thought, by the glance of his eye, by the power of his word, by the strength of his will, he hurls back that living stream of the enemy and snatches victory from the jaws of defeat. How bold in war, how gentle in peace. On some few occasions in Washington I had the pleasure of metting Gen. Sheridan socially in private circles I was forcibly struck by his gentle disposition, his amiable manner, his unassuming deportment, his eye beaming with good nature, and his voice scarcely raised above a whisper. I said to myself: is this bashful man and retiring citizen the great General of the Army? Is this the hero of so many battles?

It is true Gen. Sheridan has been charged with being sometimes unnecessarily sever toward the enemy. My conversations with him strongly impressed me with the groundlessness of a charge which could in no way be reconciled with the abhorrence which he expressed for the atrocities of war, with his natural aversion to bloodshed, and with the hope he uttered that he would never again be obliged to draw his sword against an enemy. I am persuaded that the sentiments of humanity ever found a congenial home, a secure lodgment in the breast of Gen. Sheridan. Those who are best acquainted with his military career unite in saying that he never needlessly sacrificed human life, and that he loved and cared for his soldiers as a father loves and cares for his children. But we must not forget that if the departed hero was a soldier, he was, too, a citizen; and if we wish to know how a man stands as a citizen, we must ask ourselves how he stands as a son, husband and father. The parent is the source of the family, the family is the source of the Nation. Social life is the reflex of the family life. The stream does not rise above its source. Those who were admitted into the inner circle of Gen. Sheridan’s home need not be told that it was a peaceful and happy one. He was a fond husband and an affectionate father, lovingly devoted to his wife and children. I hope I am not trespassing upon the sacred privacy of domestic life when I state that the General’s sickness was accelerated, if not aggravated, by a fatiguing journey which he made in order to be home in time to assist at a domestic celebration in which one of his children was the central figure.

Above all, Gen. Sheridan was a Christian. He died fortified by the consolations of religion, having his trust in the saving mercies of our Redeemer and a humble hope in a blessed immortality. What is life without the hope of immortality? What is life that is bounded by the horizon of the tomb? Surely it is not worth living. What is the life even of the antediluvian patriarchs but like the mist which is dispelled by the morning sun? What would it profit the illustrious hero to go down to his honored grave covered with earthly glory if he had no hope in the eternal glory to come? It is the hope of eternal life that constitutes at once our dignity and our moral responsibility. God has planted in the human breast an irresistible desire for immortality. It is born with us and lives and moves with us. It inspires our best and holiest actions. Now, God would not have given us this desire if He did not intend that it should be fully satisfied. He would not have given us this thirst for infinite happiness if He had not intended to assuage it. He never created anything in vain. Thanks to God, this universal yearning of the human heart is sanctioned and vindicated by the voice of revelation. The inspired word of God not only proclaims the immortality of the soul, but also the future resurrection of the body. “I know,” says the Prophet Job, “that my Redeemer liveth, and on the last I day I shall rise out of the earth and in my flesh I shall see my God.” “Wonder not at this,” says our Saviour, “for the hour cometh when all that are in their graves shall hear the voice of the Son of Man, and they who have done well shall come forth to the resurrection of life, and they who have done ill to the resurrection of judgment.” And the Apostle writes these comforting words to the Thessalonians: “I would not have you ignorant, brethren, concerning those that are asleep, that ye be not sorrowful like those that have no hope; for if we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so those who have died in Jesus, God will raise unto Himself. Therefore comfort yourself with these words.”

These are the words of comfort I I would address to you, Madam, faithful consort of the illustrious dead. This is the olive branch of peace and hope I would bring you today. This is the silver lining of the cloud which hangs over you. We followed you in spirit and with sympathizing hearts as you knelt in prayer at the bed of your dying husband. May the God of all consolation comfort you in this hour of sorrow. May the soul of your husband be this day in peace and his abode in Zion. May his memory be ever enshrined in the hearts of his countrymen, and may our beloved country, which he loved and served so well, ever be among the foremost nations of the earth, the favored land of constitutional freedom, strong in the loyalty of its patriotic citizens and in the genius and valor of its soldiers, till time shall be no more.

Comrades and companions of the illustrious dead, take hence your great leader, bear him to his last resting place, carry him gently, lovingly, and though you may not hope to attain his exalted rank, you will strive, at least, to emulate him by the integrity of your private life, by your devotion to your country, and by upholding the honor of your military profession.